2025 AAG Awards Recognition

AAG Honors

AAG Honors are offered annually to recognize outstanding accomplishments by members in research and scholarship, teaching, education, service to the discipline, public service outside academe and for lifetime achievement.

AAG Distinguished Scholarship Honors

Jiquan Chen

Professor Jiquan Chen has received the 2025 AAG Distinguished Scholarship Honor in recognition of his transformative impact on geography and environmental science. With over 600 publications and more than $30 million in research funding, Dr. Chen has made significant advances in understanding global ecosystems and the interactions between humans and nature. His groundbreaking SESometry framework has provided a new approach to measuring and analyzing the socioecological impacts of climate change, influencing both policy and scientific research worldwide.

Professor Jiquan Chen has received the 2025 AAG Distinguished Scholarship Honor in recognition of his transformative impact on geography and environmental science. With over 600 publications and more than $30 million in research funding, Dr. Chen has made significant advances in understanding global ecosystems and the interactions between humans and nature. His groundbreaking SESometry framework has provided a new approach to measuring and analyzing the socioecological impacts of climate change, influencing both policy and scientific research worldwide.

A fellow of both the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the Ecological Society of America, Dr. Chen’s contributions have reshaped landscape ecology and sustainable resource management. Through his leadership at Michigan State University’s Landscape Ecology and Ecosystem Science Lab, he has also mentored the next generation of scholars, extending his influence across the field. His achievements reflect an unwavering commitment to scientific innovation and the pursuit of sustainable solutions to global challenges.

Xinyue Ye

Dr. Xinyue Ye was awarded the AAG Distinguished Scholarship Honor for his transformative work at the intersection of geography, urban planning, and data science. As the Harold L. Adams Endowed Professor at Texas A&M University, he has built an extensive research portfolio that spans multiple disciplines, including geography, urban planning, computer science, engineering, medicine, and public policy. His establishment of pioneering research labs, such as the Urban AI Lab and Computational Social Science Lab, has significantly advanced urban informatics, employing innovative tools like digital twin infrastructures and virtual/augmented reality to enhance urban planning and resilience.

Dr. Xinyue Ye was awarded the AAG Distinguished Scholarship Honor for his transformative work at the intersection of geography, urban planning, and data science. As the Harold L. Adams Endowed Professor at Texas A&M University, he has built an extensive research portfolio that spans multiple disciplines, including geography, urban planning, computer science, engineering, medicine, and public policy. His establishment of pioneering research labs, such as the Urban AI Lab and Computational Social Science Lab, has significantly advanced urban informatics, employing innovative tools like digital twin infrastructures and virtual/augmented reality to enhance urban planning and resilience.

Dr. Ye’s work has secured over $30 million in external grants, demonstrating his ability to attract substantial research support. His interdisciplinary approach has fostered collaboration across 18 academic departments, resulting in widely cited publications and policy-relevant contributions. Dr. Ye’s commitment to community impact is evident in his projects that address socioeconomic disparities, environmental resilience, and spatial data accessibility, particularly benefiting underserved communities.

AAG Gilbert Grosvenor Honors for Geographic Education

J. Scott Greene

Dr. Scott Greene is recognized with the 2025 Gilbert Grosvenor Honors for Geographic Education Award, celebrating his remarkable dedication to advancing geographic education. Known for his tireless commitment, Dr. Greene’s teaching excellence has earned him several awards including the University of Oklahoma’s highest teaching honor, the prestigious Regents Award for Superior Teaching.

Dr. Scott Greene is recognized with the 2025 Gilbert Grosvenor Honors for Geographic Education Award, celebrating his remarkable dedication to advancing geographic education. Known for his tireless commitment, Dr. Greene’s teaching excellence has earned him several awards including the University of Oklahoma’s highest teaching honor, the prestigious Regents Award for Superior Teaching.

His current leadership positions include coordinator of the Oklahoma Alliance for Geographic Education (OKAGE ) and board member of the National Council for Geographic Education. While he was chair of OU’s Department of Geography and Environmental Sustainability, he engaged deeply in educational outreach and initiated inclusive dialogue through his support and sponsorship of the “Uncomfortable Conversations in Comfy Chairs” program. His collaboration with the National Geographic Society showcases his innovative approach to teaching and his commitment to providing educators with professional development, original and effective teaching strategies, classroom materials, and model geography education programs. This partnership is exemplified by the Slingshot Challenge which engages youth in addressing environmental issues. The Oklahoma program achieved the nation’s second-highest participation under his guidance.

Dr. Greene’s commitment to professional development has led him to work directly with Oklahoma K-12 educators and to provide resources such as Giant Traveling Maps, which inspire geographic inquiry and critical thinking. Dr. Greene has also influenced state legislation, secured resources and helped develop geography education standards. Under Dr. Greene’s leadership, OKAGE has demonstrated a commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion through prioritizing engagement with rural, Title I and BIPOC schools statewide.

Lifetime Achievement Honors

Victoria Lawson

The American Association of Geographers awards the AAG Lifetime Achievement Honors to Dr. Victoria Lawson for her outstanding contributions to geographical research, teaching and mentoring, and disciplinary service. Lawson has published pathbreaking research at the intersection of feminist economic and social geography. Lawson’s initial work was on migration and informal work in Ecuador. Lawson’s ensuing research focuses on rural poverty issues in the United States, leading to the formation of the Relational Poverty Network that charted a new course for geographical relational poverty thinking. Over her 40-year career, Lawson played a leading role in helping to advance feminist care ethics approaches in geographical research.

The American Association of Geographers awards the AAG Lifetime Achievement Honors to Dr. Victoria Lawson for her outstanding contributions to geographical research, teaching and mentoring, and disciplinary service. Lawson has published pathbreaking research at the intersection of feminist economic and social geography. Lawson’s initial work was on migration and informal work in Ecuador. Lawson’s ensuing research focuses on rural poverty issues in the United States, leading to the formation of the Relational Poverty Network that charted a new course for geographical relational poverty thinking. Over her 40-year career, Lawson played a leading role in helping to advance feminist care ethics approaches in geographical research.

Lawson’s passion for research has been matched by equal dedication to teaching, mentoring, and increasing the representation of women in the geographical sciences. Lawson advocates for expanding access to underrepresented groups within academia. Her efforts have been critical to making the geographical discipline stronger and more inclusive today. For her commitment to mentorship and excellence in teaching, she has received several awards and honors, including Marsha Landolt Distinguished Graduate Mentor Award, the University of Washington Distinguished Teaching Award, and the Solomon Katz Distinguished Lectureship in the Humanities. In her long service to geographers and geography, Lawson served as department chair, founded the AAG Healthy Departments Initiative, was chair of AAG National Councilors and is a past president of the AAG. Beyond her scholarship prowess, excellence in teaching, and distinguished service, Lawson’s contribution is best demonstrated in her caring humanity, deep sense of ethics, and professionalism.

Rickie Sanders

The American Association of Geographers awards the 2025 Lifetime Achievement Honors to Dr. Rickie Sanders. For four decades, her scholarship, transformative teaching, and visionary leadership have reshaped multiple disciplines and had an influence well beyond academia. Sanders, Professor Emerita in Geography at Temple University, is the first Black woman in the United States to earn a Ph.D. in Geography and the first Black woman in the United States to earn the rank of Professor in the discipline. Sanders was among the first to integrate race and gender in geographic research. Sanders has held significant leadership roles, including heading Temple’s Geography and Urban Studies Department and Women’s Studies Program, and has received grant funding to support her innovative work in geographic education.

The American Association of Geographers awards the 2025 Lifetime Achievement Honors to Dr. Rickie Sanders. For four decades, her scholarship, transformative teaching, and visionary leadership have reshaped multiple disciplines and had an influence well beyond academia. Sanders, Professor Emerita in Geography at Temple University, is the first Black woman in the United States to earn a Ph.D. in Geography and the first Black woman in the United States to earn the rank of Professor in the discipline. Sanders was among the first to integrate race and gender in geographic research. Sanders has held significant leadership roles, including heading Temple’s Geography and Urban Studies Department and Women’s Studies Program, and has received grant funding to support her innovative work in geographic education.

Recipient of numerous awards from the AAG and NCGE, her legacy of anti-racist, intersectional practices has revolutionized the discipline. Most recently, the AAG’s Feminist Geographies Specialty Group created the Rickie Sanders Junior Faculty Award. Importantly, Sanders has served as a mentor and role model for Black women, women of color, Black men, and LGBT2QIA+ people, advocating for their presence and success in geography and academia. Sanders’s career is a testament to the metamorphic power of social justice.

AAG Media Achievement Award

Cary Mock

The 2025 Media Achievement Award is presented to Dr. Cary Mock for his exceptional and outstanding communication of geographical and climatological insights to broadcast, print, and social media. He has given well over 200 interviews since 2000 to a wide range of local, national, and international media outlets, ranging from local newspapers to the Washington Post, the Guardian, Reuters, and the Associated Press. He has spoken on radio, including Voice of America, and appeared on numerous television stations in the US, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Professor Mock is highly regarded for his ability to convey climate information in ways that are compelling and relatable to varied audiences and he is especially sought after for his ability to not only explain the science of current weather patterns, but also to put current events in historical contexts. His detailed, thorough archival research of climate history enables him to authoritatively compare current climate extremes to historical events. Through decades of carefully communicating climate knowledge, Cary Mock has developed networks of trusted relationships with media and become a reliable, informative voice and excellent role model.

The 2025 Media Achievement Award is presented to Dr. Cary Mock for his exceptional and outstanding communication of geographical and climatological insights to broadcast, print, and social media. He has given well over 200 interviews since 2000 to a wide range of local, national, and international media outlets, ranging from local newspapers to the Washington Post, the Guardian, Reuters, and the Associated Press. He has spoken on radio, including Voice of America, and appeared on numerous television stations in the US, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Professor Mock is highly regarded for his ability to convey climate information in ways that are compelling and relatable to varied audiences and he is especially sought after for his ability to not only explain the science of current weather patterns, but also to put current events in historical contexts. His detailed, thorough archival research of climate history enables him to authoritatively compare current climate extremes to historical events. Through decades of carefully communicating climate knowledge, Cary Mock has developed networks of trusted relationships with media and become a reliable, informative voice and excellent role model.

AAG Fellows

The AAG Fellows is a recognition and service program that applauds geographers who have made significant contributions to advancing geography.

The 2024-2025 AAG Fellows selection committee: Budhu Badhuri, Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Steven Manson, University of Minnesota Twin Cities; Anne Chin, Florida State University; Doug Allen, Florida State University; Sara McLafferty, University of Illinois; and Alex Moulton, CUNY – Hunter College.

David Cairns

Dr. David Cairns is a respected and innovative biogeographer who integrates diverse field studies to understand how ecological and geomorphic patterns and processes are shaped by gradients in environmental conditions, disturbance regimes, and climate change. His work straddles specialty groups and scientific communities, and he has received honors from several, including the Henry C. Cowles Award from the American Association of Geographers (AAG) Biogeography Specialty Group. He is also a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Cairns’ research focus in the high Arctic has been a significant part of his career, and he currently serves as president of the Board of Directors of the Arctic Research Consortium of the United States, which coordinates international and interdisciplinary work in the Arctic, and was integral to the development and activities of the International Polar Year research program. He served in various capacities for the AAG, including serving as chair and board member for the Biogeography Specialty Group, and as a reviewer on AAG journals and student paper competitions. He made impressive efforts to implement equity and diversity policies at Texas A&M University. Dr. Cairns has provided a model of mentorship and collaboration that elevates all of the voices in a room, and has a laudable track record of teaching and mentoring. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. David Cairns as an AAG Fellow.

Dr. David Cairns is a respected and innovative biogeographer who integrates diverse field studies to understand how ecological and geomorphic patterns and processes are shaped by gradients in environmental conditions, disturbance regimes, and climate change. His work straddles specialty groups and scientific communities, and he has received honors from several, including the Henry C. Cowles Award from the American Association of Geographers (AAG) Biogeography Specialty Group. He is also a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Cairns’ research focus in the high Arctic has been a significant part of his career, and he currently serves as president of the Board of Directors of the Arctic Research Consortium of the United States, which coordinates international and interdisciplinary work in the Arctic, and was integral to the development and activities of the International Polar Year research program. He served in various capacities for the AAG, including serving as chair and board member for the Biogeography Specialty Group, and as a reviewer on AAG journals and student paper competitions. He made impressive efforts to implement equity and diversity policies at Texas A&M University. Dr. Cairns has provided a model of mentorship and collaboration that elevates all of the voices in a room, and has a laudable track record of teaching and mentoring. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. David Cairns as an AAG Fellow.

Gang Chen

Dr. Gang Chen has an exemplary track record of leadership and service at multiple levels. This includes, among other things, leadership of the Landscape Specialty Group to service on the Southeastern Division of the AAG (SEDAAG) Program committee to the editorship of the journal Remote Sensing of Environment. A professor in the Department of Earth, Environmental and Geographical Sciences, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Dr. Chen’s scholarship spans environmental sustainability, geospatial analytics, and remote sensing. Dr. Chen’s research has contributed to the development of novel geospatial models and datasets that advance Earth observation, big data analytics, and enhanced accessibility of geographic services to underserved communities. Dr. Chen is a beloved mentor who has served as faculty advisor to 46 students, from high school sophomores to postdoctoral fellows. Passionate about justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion, Dr. Chen has strived to improve representation of women within the male-dominated field of remote sensing and has undertaken numerous professional development initiatives, workshops, and community outreach events to support the next generation of geographers. These efforts span advising two NGOs – Sustain Charlotte and TreesCharlotte in environmental protection using green infrastructure, giving ‘Science Saturdays’ talks at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences for K-12 students and their families, and developing remote sensing workshops for urban planners and students in Bangkok, Thailand. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Gang Chen as an AAG Fellow.

Dr. Gang Chen has an exemplary track record of leadership and service at multiple levels. This includes, among other things, leadership of the Landscape Specialty Group to service on the Southeastern Division of the AAG (SEDAAG) Program committee to the editorship of the journal Remote Sensing of Environment. A professor in the Department of Earth, Environmental and Geographical Sciences, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Dr. Chen’s scholarship spans environmental sustainability, geospatial analytics, and remote sensing. Dr. Chen’s research has contributed to the development of novel geospatial models and datasets that advance Earth observation, big data analytics, and enhanced accessibility of geographic services to underserved communities. Dr. Chen is a beloved mentor who has served as faculty advisor to 46 students, from high school sophomores to postdoctoral fellows. Passionate about justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion, Dr. Chen has strived to improve representation of women within the male-dominated field of remote sensing and has undertaken numerous professional development initiatives, workshops, and community outreach events to support the next generation of geographers. These efforts span advising two NGOs – Sustain Charlotte and TreesCharlotte in environmental protection using green infrastructure, giving ‘Science Saturdays’ talks at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences for K-12 students and their families, and developing remote sensing workshops for urban planners and students in Bangkok, Thailand. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Gang Chen as an AAG Fellow.

Lorraine Dowler

Dr. Lorraine Dowler has played a significant and sustained role in advancing geography through her exceptional research, service, and teaching innovations. She has shaped the field of feminist geography by mentoring a generation of feminist scholars and documenting the ties between the gendered spaces of daily life and state politics, power, and militarization. Internationally renowned for her work on feminist geopolitics, Dr. Dowler raises key questions about the gendering of identities in geopolitics, the power dynamics underpinning them, and the blurred boundaries between public and private spaces. She has had a central role in efforts to advance and improve our discipline through her service on AAG Council and Finance committee and her leadership of initiatives like the Task Force for a Harassment-Free AAG. Within her university, she has held a range of leadership positions, from overseeing initiatives around justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion to the headship of Women’s Studies. An exceptional and dedicated mentor, Dr. Dowler is diagnosing obstacles to access and exposing bias and harassment while mentoring new generations of geographic scholars at the intersection of her department, college, and profession. Recipient of teaching and mentoring awards, she has initiated innovations in undergraduate curriculum such as the Apocalyptic Geographies course, which challenges students to use a geographic perspective in analyzing contemporary global justice issues.

Dr. Lorraine Dowler has played a significant and sustained role in advancing geography through her exceptional research, service, and teaching innovations. She has shaped the field of feminist geography by mentoring a generation of feminist scholars and documenting the ties between the gendered spaces of daily life and state politics, power, and militarization. Internationally renowned for her work on feminist geopolitics, Dr. Dowler raises key questions about the gendering of identities in geopolitics, the power dynamics underpinning them, and the blurred boundaries between public and private spaces. She has had a central role in efforts to advance and improve our discipline through her service on AAG Council and Finance committee and her leadership of initiatives like the Task Force for a Harassment-Free AAG. Within her university, she has held a range of leadership positions, from overseeing initiatives around justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion to the headship of Women’s Studies. An exceptional and dedicated mentor, Dr. Dowler is diagnosing obstacles to access and exposing bias and harassment while mentoring new generations of geographic scholars at the intersection of her department, college, and profession. Recipient of teaching and mentoring awards, she has initiated innovations in undergraduate curriculum such as the Apocalyptic Geographies course, which challenges students to use a geographic perspective in analyzing contemporary global justice issues.

Lesley-Ann L. Dupigny-Giroux

Dr. Dupigny-Giroux is a University Distinguished Professor of Geography and Geosciences at the University of Vermont. She is also the state climatologist of Vermont and a recognized leader in hydroclimatic natural hazards, climate literacy and climate services. Her research intersects climate science, hydrology, remote sensing, and geographic information science. She was lead editor of “Historical climate variability and impacts in North America,” a first monograph of its kind that uses documentary and ancillary records in analyzing climate variability and change. She has contributed to all five National Climate Assessments, and served a major role on the 3rd and 4th National Climate Assessments. A highly sought-after speaker, Dr. Dupigny-Giroux has focused on climate literacy to help citizens, municipalities and legislators understand how climate science can inform decisions and improve quality of life. Her numerous leadership roles include serving as president of the American Association of State Climatologists, member of the American Meteorological Society’s Applied Climatology Committee, member of the NOAA Science Advisory Board Climate Working Group, and member of three committees/boards of the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine. A Fellow of the American Meteorological Society, she was also an AAG National Councilor and Chair of the Climate Specialty Group, which has honored her with the Lifetime Achievement Award. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Lesley-Ann Dupigny-Giroux as an AAG Fellow. (Photo: Steve Exler, VT EPSCoR program, University of Vermont)

Dr. Dupigny-Giroux is a University Distinguished Professor of Geography and Geosciences at the University of Vermont. She is also the state climatologist of Vermont and a recognized leader in hydroclimatic natural hazards, climate literacy and climate services. Her research intersects climate science, hydrology, remote sensing, and geographic information science. She was lead editor of “Historical climate variability and impacts in North America,” a first monograph of its kind that uses documentary and ancillary records in analyzing climate variability and change. She has contributed to all five National Climate Assessments, and served a major role on the 3rd and 4th National Climate Assessments. A highly sought-after speaker, Dr. Dupigny-Giroux has focused on climate literacy to help citizens, municipalities and legislators understand how climate science can inform decisions and improve quality of life. Her numerous leadership roles include serving as president of the American Association of State Climatologists, member of the American Meteorological Society’s Applied Climatology Committee, member of the NOAA Science Advisory Board Climate Working Group, and member of three committees/boards of the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine. A Fellow of the American Meteorological Society, she was also an AAG National Councilor and Chair of the Climate Specialty Group, which has honored her with the Lifetime Achievement Award. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Lesley-Ann Dupigny-Giroux as an AAG Fellow. (Photo: Steve Exler, VT EPSCoR program, University of Vermont)

Timothy Hawthorne

Dr. Timothy Hawthorne’s career has been focused on community, from his pioneering research in community geography to his leadership in student engagement with participatory research. His innovative vision, creating mobile GIS labs to bring geoscience technology to high-need schools and communities, has made GIS an accessible science and tool for communities. These efforts have advanced geography as a participatory, citizen science. Dr. Hawthorne has been a leader within Applied Geography and geographic education, and he has been an award-winning mentor during his career. Just as his research has been focused on community engagement, his teaching and mentorship has been dedicated to advocating for geography students and providing opportunities for students to get involved in the field, showing them that geography is a discipline engaged in the real world with real peoples’ lives. His publicly engaged research in Belize illustrates how Dr. Hawthorne unites his research, teaching, and mentorship in a participatory, community project. Through long-standing research with a community with which he has built strong ties, Dr. Hawthorne invites students to participate in publicly engaged research. This combination of community research, innovative geographic mobile labs, and student-centered, and participatory field work research both in the US and abroad shows that Dr. Hawthorne is the quintessential scholar-teacher. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Timothy Hawthorne as an AAG Fellow.

Dr. Timothy Hawthorne’s career has been focused on community, from his pioneering research in community geography to his leadership in student engagement with participatory research. His innovative vision, creating mobile GIS labs to bring geoscience technology to high-need schools and communities, has made GIS an accessible science and tool for communities. These efforts have advanced geography as a participatory, citizen science. Dr. Hawthorne has been a leader within Applied Geography and geographic education, and he has been an award-winning mentor during his career. Just as his research has been focused on community engagement, his teaching and mentorship has been dedicated to advocating for geography students and providing opportunities for students to get involved in the field, showing them that geography is a discipline engaged in the real world with real peoples’ lives. His publicly engaged research in Belize illustrates how Dr. Hawthorne unites his research, teaching, and mentorship in a participatory, community project. Through long-standing research with a community with which he has built strong ties, Dr. Hawthorne invites students to participate in publicly engaged research. This combination of community research, innovative geographic mobile labs, and student-centered, and participatory field work research both in the US and abroad shows that Dr. Hawthorne is the quintessential scholar-teacher. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Timothy Hawthorne as an AAG Fellow.

Joshua Inwood

Dr. Joshua Inwood’s career has centered on developing theoretical frameworks to study racism, white supremacy, and the legacies of social justice movements while ensuring this research is accessible and impactful to multiple audiences. His work has positioned him as a leading voice in examining white supremacy within the field of geography, illustrating how geographic concepts and practices both perpetuate racial oppression and serve as tools for resistance. At the core of Dr. Inwood’s scholarship is an exploration of power dynamics in social and political discourse, alongside a commitment to understanding how grassroots resistance movements challenge systems of oppression and demand accountability. Dr. Inwood is widely recognized as one of geography’s most effective advocates and communicators. Through public forums, he demonstrates the critical role of geographic storytelling and perspectives in addressing pressing social issues. A prolific writer, he contributes extensively to both scholarly publications and broader public research platforms, bridging the gap between academia and the wider community.

Dr. Joshua Inwood’s career has centered on developing theoretical frameworks to study racism, white supremacy, and the legacies of social justice movements while ensuring this research is accessible and impactful to multiple audiences. His work has positioned him as a leading voice in examining white supremacy within the field of geography, illustrating how geographic concepts and practices both perpetuate racial oppression and serve as tools for resistance. At the core of Dr. Inwood’s scholarship is an exploration of power dynamics in social and political discourse, alongside a commitment to understanding how grassroots resistance movements challenge systems of oppression and demand accountability. Dr. Inwood is widely recognized as one of geography’s most effective advocates and communicators. Through public forums, he demonstrates the critical role of geographic storytelling and perspectives in addressing pressing social issues. A prolific writer, he contributes extensively to both scholarly publications and broader public research platforms, bridging the gap between academia and the wider community.

In addition to his research, Dr. Inwood serves as a faculty facilitator and co-organizer for workshops aimed at equipping future scholars and educators with tools to use geography as a lens for understanding and improving the world. His work exemplifies the power of geography to drive meaningful change. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Joshua Inwood as an AAG Fellow.

John Kupfer

Dr. John Kupfer is a highly productive landscape ecologist working at the interface between biogeography, ecology, and geographical information sciences. He has published over 70 papers addressing how ecological patterns and processes are shaped by gradients in environmental conditions, by disturbances such as floods and fires, and by human activities. His research is policy-relevant and actional science. In this way, he is leading biogeography into environmentally important and exciting areas for the 21st century. His research has been recognized twice by the Henry Cowles Award for Excellence in Publication from the Biogeography Specialty Group of the AAG. He is also an award-winning teacher. Additionally, he has provided valuable service to the AAG on numerous committees that include the Governing Council, the Search Committee for the Executive Director of the AAG, the Presidential Taskforce on the State of AAG Regions, and the Honors and Publications committees. He was also president of the Biogeography Specialty Group. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. John Kupfer as an AAG Fellow.

Dr. John Kupfer is a highly productive landscape ecologist working at the interface between biogeography, ecology, and geographical information sciences. He has published over 70 papers addressing how ecological patterns and processes are shaped by gradients in environmental conditions, by disturbances such as floods and fires, and by human activities. His research is policy-relevant and actional science. In this way, he is leading biogeography into environmentally important and exciting areas for the 21st century. His research has been recognized twice by the Henry Cowles Award for Excellence in Publication from the Biogeography Specialty Group of the AAG. He is also an award-winning teacher. Additionally, he has provided valuable service to the AAG on numerous committees that include the Governing Council, the Search Committee for the Executive Director of the AAG, the Presidential Taskforce on the State of AAG Regions, and the Honors and Publications committees. He was also president of the Biogeography Specialty Group. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. John Kupfer as an AAG Fellow.

Zhenlong Li

Dr. Zhenlong Li is an associate professor in the Department of Geography at Pennsylvania State University and leads the Geoinformation and Big Data Research Laboratory. He is a leading scholar in GIScience focusing on geospatial big data, spatial computing, and geospatial AI. His research aims to enhance knowledge discovery and decision-making regarding hazards, public health, population mobility, and climate change. His work is widely recognized with over 100 well-cited articles published in top-tier international journals, supported by extensive research grants from prestigious sponsors including NSF and NIH. Dr. Li emphasizes equipping future GIScientists with strong problem-solving abilities by integrating spatial and computational thinking in his teaching and advising, and a number of his mentees have secured prominent academic and professional positions. He currently serves as an associate editor of the International Journal of Digital Earth and International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation. Previously, he served as the Chair of the AAG Cyberinfrastructure Specialty Group and co-Chair of Earth Science Information Partnership (ESIP) Cloud Computing Group. Dr. Li’s significant contributions to the advancement of GIScience and his role as a rising leader in the discipline make him a valued member of the geography community and a deserving recipient of the AAG Fellow distinction. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Zhenlong Li as an AAG Fellow.

Dr. Zhenlong Li is an associate professor in the Department of Geography at Pennsylvania State University and leads the Geoinformation and Big Data Research Laboratory. He is a leading scholar in GIScience focusing on geospatial big data, spatial computing, and geospatial AI. His research aims to enhance knowledge discovery and decision-making regarding hazards, public health, population mobility, and climate change. His work is widely recognized with over 100 well-cited articles published in top-tier international journals, supported by extensive research grants from prestigious sponsors including NSF and NIH. Dr. Li emphasizes equipping future GIScientists with strong problem-solving abilities by integrating spatial and computational thinking in his teaching and advising, and a number of his mentees have secured prominent academic and professional positions. He currently serves as an associate editor of the International Journal of Digital Earth and International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation. Previously, he served as the Chair of the AAG Cyberinfrastructure Specialty Group and co-Chair of Earth Science Information Partnership (ESIP) Cloud Computing Group. Dr. Li’s significant contributions to the advancement of GIScience and his role as a rising leader in the discipline make him a valued member of the geography community and a deserving recipient of the AAG Fellow distinction. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Zhenlong Li as an AAG Fellow.

Corene Matyas

Dr. Corene Matyas has dedicated their career to producing exceptional, community relevant climate research and communication, guiding and mentoring the future generations of geography and climatology scholars, and creating space for marginalized peoples in the discipline. Dr. Matyas’ research studying the precipitation patterns within hurricanes is critically important as we increasingly need to understand heavy precipitation landfalls and how human perceptions of perceived risk impact assessments and actions in the face of these storms. Dr. Matyas’ research is coupled with their exceptional teaching. They have won teaching awards at both the college and disciplinary level and winning the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Teacher of the Year Award and the SEDAAG Excellence in Teaching Award a decade apart is a testament to the sustained impact Dr. Matyas has made in teaching and guiding students. It is this dedicated service to the future of our discipline that is a throughline for Dr. Matyas’s career. Their service as a judge for student competitions, organizer for specialty groups and societies that make space for marginalized, underrepresented scholars in geography, and their consistent mentorship of students in the classroom as well as involving them in research is inspiring. They also communicate science to diverse audiences through visual arts. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Corene Matyas as an AAG Fellow.

Dr. Corene Matyas has dedicated their career to producing exceptional, community relevant climate research and communication, guiding and mentoring the future generations of geography and climatology scholars, and creating space for marginalized peoples in the discipline. Dr. Matyas’ research studying the precipitation patterns within hurricanes is critically important as we increasingly need to understand heavy precipitation landfalls and how human perceptions of perceived risk impact assessments and actions in the face of these storms. Dr. Matyas’ research is coupled with their exceptional teaching. They have won teaching awards at both the college and disciplinary level and winning the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Teacher of the Year Award and the SEDAAG Excellence in Teaching Award a decade apart is a testament to the sustained impact Dr. Matyas has made in teaching and guiding students. It is this dedicated service to the future of our discipline that is a throughline for Dr. Matyas’s career. Their service as a judge for student competitions, organizer for specialty groups and societies that make space for marginalized, underrepresented scholars in geography, and their consistent mentorship of students in the classroom as well as involving them in research is inspiring. They also communicate science to diverse audiences through visual arts. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Corene Matyas as an AAG Fellow.

Christian Renschler

Chris S. Renschler is a Supervisory Research Soil Scientist at USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) National Soil Erosion Research Laboratory (NSERL), following a distinguished 20-year academic career with positions at eight universities on four continents, encompassing research, teaching, and outreach. As the NSERL Research Leader he leads and coordinates science and stakeholder engagement activities to develop the knowledge and technology needed by land users to conserve natural resources for future generations. A Fulbright Scholar, he is internationally recognized for his expertise in soil and water conservation, integrated watershed management, extreme events, and natural resources and hazards management, utilizing GIS and Remote Sensing technologies. His research and stakeholder engagement activities involve the development, validation, and application of integrated hydrology and erosion modeling tools, created collaboratively with scientists, engineers, and practitioners, to facilitate effective decision-making in the context of global climate change, extreme weather events, community resilience, and evolving land use and land cover patterns. Dr. Renschler has exhibited a strong commitment to service within the AAG and has held multiple leadership positions within the AAG, including chair of the Geomorphology Specialty Group, where he played a pivotal role in fostering collaboration and in advancing the group’s career development, research, and awards programs. He is an editorial board member of the Journal of Earth Science Informatics and Remote Sensing. Dr. Renschler is a past recipient of an Achievement in GIS Award from the Environmental Systems Research Institute (Esri) and currently serves as the president of the International Soil Conservation Organization (ISCO). The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Christian S. Renschler as an AAG Fellow.

Chris S. Renschler is a Supervisory Research Soil Scientist at USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) National Soil Erosion Research Laboratory (NSERL), following a distinguished 20-year academic career with positions at eight universities on four continents, encompassing research, teaching, and outreach. As the NSERL Research Leader he leads and coordinates science and stakeholder engagement activities to develop the knowledge and technology needed by land users to conserve natural resources for future generations. A Fulbright Scholar, he is internationally recognized for his expertise in soil and water conservation, integrated watershed management, extreme events, and natural resources and hazards management, utilizing GIS and Remote Sensing technologies. His research and stakeholder engagement activities involve the development, validation, and application of integrated hydrology and erosion modeling tools, created collaboratively with scientists, engineers, and practitioners, to facilitate effective decision-making in the context of global climate change, extreme weather events, community resilience, and evolving land use and land cover patterns. Dr. Renschler has exhibited a strong commitment to service within the AAG and has held multiple leadership positions within the AAG, including chair of the Geomorphology Specialty Group, where he played a pivotal role in fostering collaboration and in advancing the group’s career development, research, and awards programs. He is an editorial board member of the Journal of Earth Science Informatics and Remote Sensing. Dr. Renschler is a past recipient of an Achievement in GIS Award from the Environmental Systems Research Institute (Esri) and currently serves as the president of the International Soil Conservation Organization (ISCO). The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Christian S. Renschler as an AAG Fellow.

Kevon Rhiney

Dr. Kevon Rhiney is a mid-career scholar with an impressive record of research, leadership, mentorship, and service to the AAG. Dr. Rhiney is associate professor of Human-Environment Geography at Rutgers University and was previously on the faculty at The University of the West Indies (Jamaica). One of the leading Caribbean scholars, Dr. Rhiney has enhance understanding of small-island agrarian political ecology, critical disaster studies, and the human dimensions of global environmental change. This has included groundbreaking research on coupled human-environmental impacts of global change on smallholder coffee production. Dr. Rhiney’s service to the discipline notably includes work as editor of the journal Geography Compass, as co-founder and past chair of the AAG Caribbean Geography Specialty Group, and as a former board member and director for the AAG Development Geographies Specialty Group. His teaching and mentorship reflect a commitment to advancing the field of geography and enriching geographic education on the Caribbean as an understudied region. Dr. Rhiney has been especially active in the recruitment and mentorship of international students and students who enhance the diversity of geography. His expertise in formulating policies has been sought by highly influential organizations such as the IPCC, USAID, and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, which speaks to how Dr. Rhiney’s scholarship has reached into the influential circles beyond the academy. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Kevon Rhiney as an AAG Fellow.

Dr. Kevon Rhiney is a mid-career scholar with an impressive record of research, leadership, mentorship, and service to the AAG. Dr. Rhiney is associate professor of Human-Environment Geography at Rutgers University and was previously on the faculty at The University of the West Indies (Jamaica). One of the leading Caribbean scholars, Dr. Rhiney has enhance understanding of small-island agrarian political ecology, critical disaster studies, and the human dimensions of global environmental change. This has included groundbreaking research on coupled human-environmental impacts of global change on smallholder coffee production. Dr. Rhiney’s service to the discipline notably includes work as editor of the journal Geography Compass, as co-founder and past chair of the AAG Caribbean Geography Specialty Group, and as a former board member and director for the AAG Development Geographies Specialty Group. His teaching and mentorship reflect a commitment to advancing the field of geography and enriching geographic education on the Caribbean as an understudied region. Dr. Rhiney has been especially active in the recruitment and mentorship of international students and students who enhance the diversity of geography. His expertise in formulating policies has been sought by highly influential organizations such as the IPCC, USAID, and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, which speaks to how Dr. Rhiney’s scholarship has reached into the influential circles beyond the academy. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Kevon Rhiney as an AAG Fellow.

Emily Rosenman

Dr. Emily Rosenman is a committed and creative economic geographer with interests in urban political economy and geographies of humanitarian finance. These are exciting areas that are already advancing established geographic subfields. Her latest research applies economic geography to the US opioid epidemic, examining how pharmaceutical companies exploited health disparities for profit and identifying policy and regulatory interventions that could prevent future harm. Dr. Rosenman is the 2023-24 chair of the Economic Geography Specialty Group (having previously served as treasurer and vice chair), where she has prioritized advancing the causes of equity, diversity, and inclusion, focusing particularly on the contributions of early-career researchers. She has led the creation of an early-career keynote lecture in economic geography now held annually at AAG. She has also developed a program for undergraduate students of color from across the United States to receive mentorship on applying to graduate school in geography. These new initiatives are deeply integrated into her evolving program of scholarship, where she has written on the politics of representation and citations in economic geography, the limits of engaged pluralism, and a framework for economic geography to become more publicly engaged. With a defining interest in contemporary policy problems, Dr. Rosenman is not just a critic, but a builder of alternative ideas and institutions. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Emily Rosenman as an AAG Fellow.

Dr. Emily Rosenman is a committed and creative economic geographer with interests in urban political economy and geographies of humanitarian finance. These are exciting areas that are already advancing established geographic subfields. Her latest research applies economic geography to the US opioid epidemic, examining how pharmaceutical companies exploited health disparities for profit and identifying policy and regulatory interventions that could prevent future harm. Dr. Rosenman is the 2023-24 chair of the Economic Geography Specialty Group (having previously served as treasurer and vice chair), where she has prioritized advancing the causes of equity, diversity, and inclusion, focusing particularly on the contributions of early-career researchers. She has led the creation of an early-career keynote lecture in economic geography now held annually at AAG. She has also developed a program for undergraduate students of color from across the United States to receive mentorship on applying to graduate school in geography. These new initiatives are deeply integrated into her evolving program of scholarship, where she has written on the politics of representation and citations in economic geography, the limits of engaged pluralism, and a framework for economic geography to become more publicly engaged. With a defining interest in contemporary policy problems, Dr. Rosenman is not just a critic, but a builder of alternative ideas and institutions. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Emily Rosenman as an AAG Fellow.

Rickie Sanders

Dr. Rickie Sanders is a trailblazer in feminist and anti-racist human geography. Dr. Sanders is now professor emerita in the Department of Geography, Environment and Urban Studies at Temple University. She has the distinction of being the first Black woman in the United States to earn a Ph.D. in Geography and the first Black woman to reach the rank of full professor in an American geography department. Dr. Sanders has had a distinguished career of making metamorphic contributions to human geography, urban studies, women’s, gender, and feminist studies, and Black studies. Through her scholarship, mentorship, and service at different levels, Dr. Sanders has advanced diversity, equity, and inclusion within the discipline and has promoted initiatives that have expanded geography education. Dr. Sanders has established persistent intellectual and political commitments that have contributed to the development and institutionalization of what we now call Black Geographies. As such, her scholarship has provided critical texts, methodologies, theoretical frameworks, and practices of community-engaged practice and that have been instructive for a wave of Black geographers and geographers studying race and place. Her mentorship and advocacy have been characterized by an energetic commitment to recruiting, charting paths for, and improving the retention of Black women, women of color, and Black men within geography. Tellingly, the Feminist Geographies Specialty Group of the AAG, created a named award in her honor, the Rickie Sanders Junior Faculty Award, in recognition of intersectional-anti-racist feminist geographies.

Dr. Rickie Sanders is a trailblazer in feminist and anti-racist human geography. Dr. Sanders is now professor emerita in the Department of Geography, Environment and Urban Studies at Temple University. She has the distinction of being the first Black woman in the United States to earn a Ph.D. in Geography and the first Black woman to reach the rank of full professor in an American geography department. Dr. Sanders has had a distinguished career of making metamorphic contributions to human geography, urban studies, women’s, gender, and feminist studies, and Black studies. Through her scholarship, mentorship, and service at different levels, Dr. Sanders has advanced diversity, equity, and inclusion within the discipline and has promoted initiatives that have expanded geography education. Dr. Sanders has established persistent intellectual and political commitments that have contributed to the development and institutionalization of what we now call Black Geographies. As such, her scholarship has provided critical texts, methodologies, theoretical frameworks, and practices of community-engaged practice and that have been instructive for a wave of Black geographers and geographers studying race and place. Her mentorship and advocacy have been characterized by an energetic commitment to recruiting, charting paths for, and improving the retention of Black women, women of color, and Black men within geography. Tellingly, the Feminist Geographies Specialty Group of the AAG, created a named award in her honor, the Rickie Sanders Junior Faculty Award, in recognition of intersectional-anti-racist feminist geographies.

Jane Southworth

Dr. Southworth is a leader in land change, human-environment dynamics, geographic information science, and remote sensing; and more recently the thoughtful engagement with artificial intelligence and big data to address pressing environmental challenges. Her research exemplifies how scholarship can be performed by highly interdisciplinary research teams that involve both social and environmental scientists. She has worked to broaden diversity and inclusion in AAG, especially in terms of transforming remote sensing in the AAG and beyond to be more inclusive of women, and founding and directing the Women in Geography group at the University of Florida. She has served as a Department Chair for 9 years, where she built a track record of incorporating and implementing innovative ideas to expand geography’s standing within the college and beyond. She serves on the AAG task force on nurturing undergraduate geography education and is a past winner of the Association’s E. Willard and Ruby S. Miller Award. She is a sought-after mentor and has shepherded dozens of master’s and doctoral graduate students who have gone on to significant positions in academia, government, and industry. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Jane Southworth as an AAG Fellow.

Dr. Southworth is a leader in land change, human-environment dynamics, geographic information science, and remote sensing; and more recently the thoughtful engagement with artificial intelligence and big data to address pressing environmental challenges. Her research exemplifies how scholarship can be performed by highly interdisciplinary research teams that involve both social and environmental scientists. She has worked to broaden diversity and inclusion in AAG, especially in terms of transforming remote sensing in the AAG and beyond to be more inclusive of women, and founding and directing the Women in Geography group at the University of Florida. She has served as a Department Chair for 9 years, where she built a track record of incorporating and implementing innovative ideas to expand geography’s standing within the college and beyond. She serves on the AAG task force on nurturing undergraduate geography education and is a past winner of the Association’s E. Willard and Ruby S. Miller Award. She is a sought-after mentor and has shepherded dozens of master’s and doctoral graduate students who have gone on to significant positions in academia, government, and industry. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Jane Southworth as an AAG Fellow.

Robert Stewart

Robert Stewart is a Distinguished Scientist in the Spatial Statistics group at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory and a professor in the Bredesen Center Data Science Track at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. His research primarily centers on the geospatial dimensions of risk and decision-making under uncertainty, applying methods from spatial statistics, machine learning, and Bayesian reasoning. His research has made significant impact on a wide variety of applications including population dynamics, environmental risk, maritime safety, transport risk, built environment characterization, and change detection. He is chair of the IEEE Computational Intelligence Society’s Government Activities Committee. He is an editorial board member of the Journal Transactions in GIS and the International Journal of Geographical Information Science. Robert serves as advisor to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Nuclear Energy Agency as well as the Alan Turing Institute’s Colouring Cities Research Program. He has also chaired the AAG’s Geographic Information Science and Systems Specialty Group at AAG and has served as ORNL liaison to the World Health Organization Chemical Risk Network. Robert remains passionate about mentoring and advising the next generation of geospatial scientists. He has mentored many early and mid-career scientists and served on a number of graduate committees located across multiple departments and universities. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Robert Stewart as an AAG Fellow.

Robert Stewart is a Distinguished Scientist in the Spatial Statistics group at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory and a professor in the Bredesen Center Data Science Track at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. His research primarily centers on the geospatial dimensions of risk and decision-making under uncertainty, applying methods from spatial statistics, machine learning, and Bayesian reasoning. His research has made significant impact on a wide variety of applications including population dynamics, environmental risk, maritime safety, transport risk, built environment characterization, and change detection. He is chair of the IEEE Computational Intelligence Society’s Government Activities Committee. He is an editorial board member of the Journal Transactions in GIS and the International Journal of Geographical Information Science. Robert serves as advisor to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Nuclear Energy Agency as well as the Alan Turing Institute’s Colouring Cities Research Program. He has also chaired the AAG’s Geographic Information Science and Systems Specialty Group at AAG and has served as ORNL liaison to the World Health Organization Chemical Risk Network. Robert remains passionate about mentoring and advising the next generation of geospatial scientists. He has mentored many early and mid-career scientists and served on a number of graduate committees located across multiple departments and universities. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Robert Stewart as an AAG Fellow.

Fahui Wang

Dr. Fahui Wang, renowned GIScientist, has made seminal contributions to the development and application of spatial analysis methods for understanding spatial and social injustices in health, well-being, and access to services. He pioneered, and continues to advance, the field of spatial accessibility modeling through his work on ‘floating catchment’ methods, and their variants, that have become the gold standard in the field. Adopted by planners and analysts who evaluate health care workforce inequalities and disparities in access, his modeling approaches stand out for their policy relevance and broad impacts. Dr. Wang’s rigorous empirical research identifies communities lacking access to essential health services and informs where and how access can be improved. Organizations that have benefited from his leadership and his energy and passion for the discipline include the AAG’s Spatial Analysis and Modeling & Health and Medical Geography Specialty Groups and the International Association for Chinese Professionals in GIScience. As department chair, he led initiatives that have greatly increased the diversity of departmental faculty and provided supportive mentorship to students from underrepresented backgrounds who faced significant obstacles to success. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Fahui Wang as an AAG Fellow.

Dr. Fahui Wang, renowned GIScientist, has made seminal contributions to the development and application of spatial analysis methods for understanding spatial and social injustices in health, well-being, and access to services. He pioneered, and continues to advance, the field of spatial accessibility modeling through his work on ‘floating catchment’ methods, and their variants, that have become the gold standard in the field. Adopted by planners and analysts who evaluate health care workforce inequalities and disparities in access, his modeling approaches stand out for their policy relevance and broad impacts. Dr. Wang’s rigorous empirical research identifies communities lacking access to essential health services and informs where and how access can be improved. Organizations that have benefited from his leadership and his energy and passion for the discipline include the AAG’s Spatial Analysis and Modeling & Health and Medical Geography Specialty Groups and the International Association for Chinese Professionals in GIScience. As department chair, he led initiatives that have greatly increased the diversity of departmental faculty and provided supportive mentorship to students from underrepresented backgrounds who faced significant obstacles to success. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Fahui Wang as an AAG Fellow.

Michael Widener

Dr. Michael Widener, professor of Geography and Planning at the University of Toronto, has made original and ground-breaking contributions to health and transportation geography and provided visionary leadership and disciplinary and community service. His research has significantly shaped understandings of the social, spatial, and temporal dimensions of inequalities in food access. Combining rigorous quantitative modeling with thoughtful critical analysis, his research challenges well-worn concepts in the food access literature such as “food deserts.” He has engaged students and researchers with community partners to improve food access and health outcomes for equity-deserving populations in Toronto and across Canada. In his university leadership positions, Dr. Widener has spearheaded initiatives to support and mentor junior faculty; developed innovative curricula in key areas; tackled barriers faced by underrepresented students; and expanded research and educational ties with diverse communities. His international leadership is reflected in his service to the AAG’s Health and Medical Geography Specialty Group; co-editorship of Health and Place; and extensive committee service. An engaged and passionate mentor, Dr. Widener has worked tirelessly to build community among his students, in his department, and across the discipline of geography. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Michael Widener as an AAG Fellow.

Dr. Michael Widener, professor of Geography and Planning at the University of Toronto, has made original and ground-breaking contributions to health and transportation geography and provided visionary leadership and disciplinary and community service. His research has significantly shaped understandings of the social, spatial, and temporal dimensions of inequalities in food access. Combining rigorous quantitative modeling with thoughtful critical analysis, his research challenges well-worn concepts in the food access literature such as “food deserts.” He has engaged students and researchers with community partners to improve food access and health outcomes for equity-deserving populations in Toronto and across Canada. In his university leadership positions, Dr. Widener has spearheaded initiatives to support and mentor junior faculty; developed innovative curricula in key areas; tackled barriers faced by underrepresented students; and expanded research and educational ties with diverse communities. His international leadership is reflected in his service to the AAG’s Health and Medical Geography Specialty Group; co-editorship of Health and Place; and extensive committee service. An engaged and passionate mentor, Dr. Widener has worked tirelessly to build community among his students, in his department, and across the discipline of geography. The AAG is very proud to recognize Dr. Michael Widener as an AAG Fellow.

Presidential Achievement Award

Chosen by the AAG Past President recognizing individuals who have made long-standing and distinguished contributions to the discipline of geography.

Max Liboiron

Max Liboiron is recognized for their extraordinary work in developing participatory and anticolonial environmental science practices. Via careful critique of current academic norms and concrete examples of how we can do better, Dr. Liboiron has inspired students and scholars across Geography and the environmental sciences to change their lab manuals, citation practices, collaboration protocols, and research methods. Rather than simply calling researchers out for extractive science, Dr. Liboiron calls researchers in to participatory and reciprocal mentorship and research practices through academic publications, such as Pollution is Colonialism (2021, Duke University Press), online resources such as the CLEAR Lab Manual, and short films made in collaboration with Couple3 that “open the black box of what seem like mundane laboratory practices… that are the main vehicles for equity, humility, accountability, and the creation of a lab collective. Our goal: to do science differently, in ways that do not replicate existing power dynamics.”

Max Liboiron is recognized for their extraordinary work in developing participatory and anticolonial environmental science practices. Via careful critique of current academic norms and concrete examples of how we can do better, Dr. Liboiron has inspired students and scholars across Geography and the environmental sciences to change their lab manuals, citation practices, collaboration protocols, and research methods. Rather than simply calling researchers out for extractive science, Dr. Liboiron calls researchers in to participatory and reciprocal mentorship and research practices through academic publications, such as Pollution is Colonialism (2021, Duke University Press), online resources such as the CLEAR Lab Manual, and short films made in collaboration with Couple3 that “open the black box of what seem like mundane laboratory practices… that are the main vehicles for equity, humility, accountability, and the creation of a lab collective. Our goal: to do science differently, in ways that do not replicate existing power dynamics.”

Dr. Liboiron, a Red River Métis/Michif and settler raised in Lac la Biche, Treaty 6 territory, is a member of the Geography Department at Memorial University in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Their interdisciplinary, deeply community-engaged research brings together discard studies, environmental science, Geography, Indigenous Studies and Science and Technology Studies (STS) in the study of plastics.

Chérie Rivers

Chérie Rivers is recognized for her radical interdisciplinary and participatory geographic work, which weaves together Black and Indigenous ecologies, decolonial pedagogy, and Africana studies. A scholar of many talents, Dr. Rivers has produced two monographs—To Be Nsala’s Daughter: Decomposing the Colonial Gaze (Duke University Press 2023), and Necessary Noise: Music, Film, and Charitable Imperialism in the East of Congo (Oxford University Press, 2016), as well as an edited volume, The Art of Emergency: Aesthetics and Aid in African Crises (Oxford University Press, 2020). She also founded and runs an educational biodynamic farm, Dandelions’, that integrates the legacy of freedom farming with Black and Indigenous earth practices. To integrate her work as a scholar and a farmer, she has developed important tools for decolonial pedagogy and land-based learning, including an interdisciplinary curriculum entitled Decomposing the Colonial Gaze. Throughout, her goal is to “interrupt… modern colonialism with the transformative power of imagination” asking both what sustains us, and what we want to sustain.

Chérie Rivers is recognized for her radical interdisciplinary and participatory geographic work, which weaves together Black and Indigenous ecologies, decolonial pedagogy, and Africana studies. A scholar of many talents, Dr. Rivers has produced two monographs—To Be Nsala’s Daughter: Decomposing the Colonial Gaze (Duke University Press 2023), and Necessary Noise: Music, Film, and Charitable Imperialism in the East of Congo (Oxford University Press, 2016), as well as an edited volume, The Art of Emergency: Aesthetics and Aid in African Crises (Oxford University Press, 2020). She also founded and runs an educational biodynamic farm, Dandelions’, that integrates the legacy of freedom farming with Black and Indigenous earth practices. To integrate her work as a scholar and a farmer, she has developed important tools for decolonial pedagogy and land-based learning, including an interdisciplinary curriculum entitled Decomposing the Colonial Gaze. Throughout, her goal is to “interrupt… modern colonialism with the transformative power of imagination” asking both what sustains us, and what we want to sustain.

Dr. Rivers is a member of the Department of Geography and Environment at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. She earned a B.M. in film scoring from the Berklee College of Music, and an A.M. in Ethnomusicology and Ph.D. in African Studies from Harvard University.

AAG Honorary Geographer

Recognizes excellence in research, teaching, or writing on geographic topics by non-geographers.

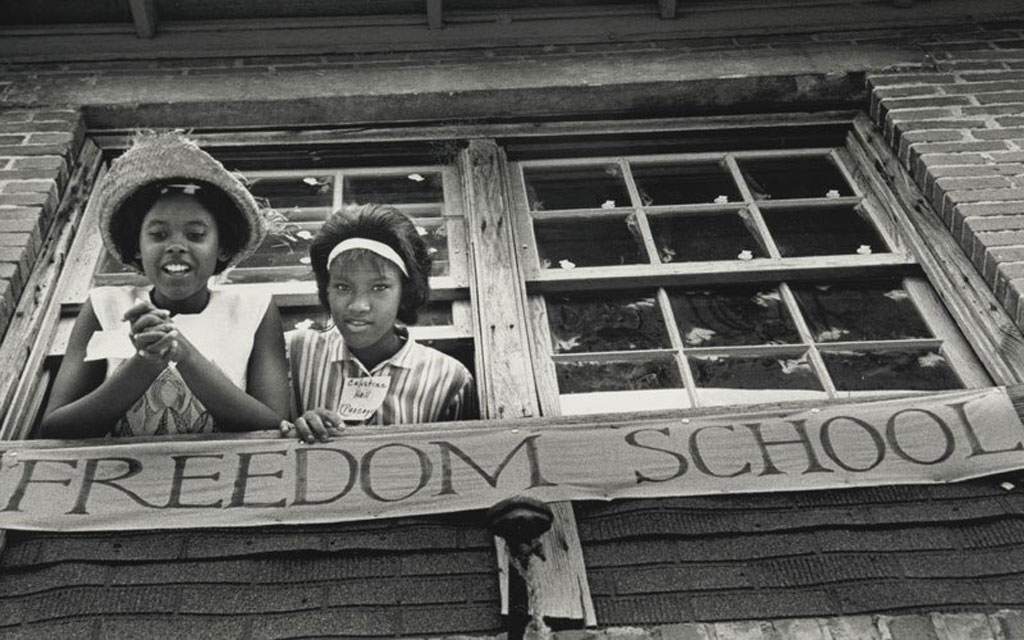

Gwendolyn C. Warren

She is recognized for her lifelong excellence in applying spatial thinking to the challenge of creating better lives and opportunities for people, starting in Detroit in the late 1960s.

She is recognized for her lifelong excellence in applying spatial thinking to the challenge of creating better lives and opportunities for people, starting in Detroit in the late 1960s.

At the age of 18, Warren was already a dedicated community activist when she became the co-director of the Detroit Geographical Expedition and Institute (DGEI). Founded in Detroit in 1968, DEIG was a radical geography research and education initiative that investigated the health, safety, and lived experiences of Detroiters, and became an enduring example of community-based and collaborative mapping for change.

Warren’s work shaped many of the DGEI’s mapping projects and led its extraordinary educational component, which made possible the training of more than 500 young women and men in applied geography with the collaboration of the Michigan State University and the State of Michigan. These “people’s geographers” then went into the field with mapping skills and tools, seeking to understand, document and map the spatial logics at work in Detroit.

As a community organizer and longtime public sector administrator, Warren has led efforts in the areas of education, health, social and community services for over 35 years. She has worked in executive-level capacities in city and county government in California, Florida, and Georgia with diverse populations that add unique and challenging issues to the provision of quality government services. She is known for her ability to leverage limited resources for innovative programs, services, and initiatives that can help people improve their wellness and self-sufficiency by accessing necessary services and building and supporting sustainable and safe neighborhoods. Her passion is to connect people, place, and resources creatively and effectively. We commend Ms. Warren for her career and this well-deserved recognition.

Previous AAG Honorary Geographer awardees have included authors Rebecca Solnit and N.K. Jemisin, philosopher Judith Butler, architect Maya Lin, Nobel Laureate in economics Paul Krugman, sociologist Saskia Sassen, economist Jeffrey Sachs, among others.

Learn more about the AAG Honorary Geographer Award

AAG Stanley Brunn Award for Creativity in Geography

Presented annually to an individual geographer or team who has demonstrated originality, creativity, and significant intellectual breakthroughs in geography.

Katherine McKittrick

As a foundational voice for Black geographies and Black methods of knowledge creation, Dr. McKittrick has re-imagined scholarship to be both documentation and instigation in modes that are poetic, sonic, material, and rhetorical. In every new, surprising iteration, her work offers “curiosity, wonder, citations, numbers, playlists, friendship, poetry, inquiry, song, grooves, and anticolonial chronologies as interdisciplinary codes that entwine with the academic form,” according to Duke University Press.

As a foundational voice for Black geographies and Black methods of knowledge creation, Dr. McKittrick has re-imagined scholarship to be both documentation and instigation in modes that are poetic, sonic, material, and rhetorical. In every new, surprising iteration, her work offers “curiosity, wonder, citations, numbers, playlists, friendship, poetry, inquiry, song, grooves, and anticolonial chronologies as interdisciplinary codes that entwine with the academic form,” according to Duke University Press.

Katherine McKittrick is professor of Gender Studies and Canada Research Chair in Black Studies at Queen’s University in Kingston, Canada. She is the author of Dear Science and Other Stories (Duke University Press 2021), which both analyzes and challenges scientific practice for its inherent ties to colonialism and anti-Blackness. Her 2006 book Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle has had a lasting impact on both Black and feminist studies since its publication by University of Minnesota Press. She has also contributed dozens of scholarly articles and edited and contributed to Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis (Duke University Press, 2015).

McKittrick continually probes the boundaries and possibilities between scholarship and imagination, challenging conventionalized methods and demonstrating the range and collective power of all ways to knowledge creation, particularly Black knowledge creation. In 2023, McKittrick published Trick Not Telos, a boxed set of texts that takes its initial inspiration from Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s reading of McKittrick’s “Plantation Futures” (Small Axe 2013, 17: 3). Although the project was initially conceived as a modest response, it grew into a creative meditation—with designer Cristian Ordóñez, project curator Liz Ikiriko, and French translator Lyse Hébert—on the nature of reiteration, revision, bibliography, and translation. In 2024, she published Twenty Dreams (2024), a limited-edition hand-made book; and is preparing an installation honoring nourbeSe philip, A Smile Split by the Stars (2025).

Learn more about the AAG Stanley Brunn Award

AAG Harold M. Rose Award for Anti-Racism Research and Practice

Honors geographers who have served to advance the discipline through their research and had on impact on anti-racist practice.

Bronwen Powell

Dr. Bronwen Powell, associate professor in the Department of Geography at Penn State University, has an exceptional record in scholarship focused on Indigenous agrobiodiversity, food and nutrition systems, and international development, grounded in the principles of social justice and anti-racism. She’s been a strong public advocate for Indigenous food sovereignty through her interdisciplinary collaborations and scholarship engagement. As the associate head for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in her department, Dr. Powell spearheaded new initiatives that were centered around Indigenous geographies and was recognized for her leadership and commitment to promoting an inclusive academic environment for students and faculty. Dr. Powell has distinguished herself through her strong dedication to anti-racism scholarship and praxis that seems to center Indigenous and African voices and perspectives. The AAG is pleased to honor Dr. Powell with the Harold M. Rose Award for Anti-Racism Research and Practice.

Dr. Bronwen Powell, associate professor in the Department of Geography at Penn State University, has an exceptional record in scholarship focused on Indigenous agrobiodiversity, food and nutrition systems, and international development, grounded in the principles of social justice and anti-racism. She’s been a strong public advocate for Indigenous food sovereignty through her interdisciplinary collaborations and scholarship engagement. As the associate head for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in her department, Dr. Powell spearheaded new initiatives that were centered around Indigenous geographies and was recognized for her leadership and commitment to promoting an inclusive academic environment for students and faculty. Dr. Powell has distinguished herself through her strong dedication to anti-racism scholarship and praxis that seems to center Indigenous and African voices and perspectives. The AAG is pleased to honor Dr. Powell with the Harold M. Rose Award for Anti-Racism Research and Practice.

Diversity & Inclusion Award

Honors geographers who have pioneered efforts toward or actively participated in efforts toward encouraging a more diverse discipline over the course of several years.

Jieun Lee

Dr. Jieun Lee, Associate Professor of Geography, GIS, and Sustainability at the University of Northern Colorado, is recognized for her deep and sustained commitment to increasing diversity and equity in geography at the departmental, institutional, and national levels. Dr. Lee is explicitly recognized for empowering foreign-born women working in U.S. academic institutions in geography and the geospatial sciences. Dr. Lee played a leadership role in creating the Golden Compass program, which provides a safe and supportive environment for international women scholars to share their experiences, build networks, and receive mentoring. Building on the early success of an inaugural workshop, she secured grant funding from the National Science Foundation, in partnership with the Association of American Geographers and the University of Consortium for Geographic Information Science (UCGIS), to expand the reach and impact of the program over the next four years. Her visionary initiative is putting inclusive excellence into practice and opening new leadership opportunities for diverse scholars in the discipline.