As geographers, we all know the value of geography. Right? It is a field that provides a unique perspective, an appreciation for particularity, an opportunity to synthesize. But as much as we affirm geography’s value to each other, we also need to look at how geography is perceived outside of our community.

As geographers, we all know the value of geography. Right? It is a field that provides a unique perspective, an appreciation for particularity, an opportunity to synthesize. But as much as we affirm geography’s value to each other, we also need to look at how geography is perceived outside of our community.

In this regard, the last year or so has been sobering, at least for Geography in the United States. Geography degrees have been closed in some universities, including Boston University, whose Geography Ph.D. program did so well in the last National Research Council ratings. Geography has been threatened (but ultimately spared) at others, despite reorganization and faculty layoffs. Then, to add insult to injury, a recent report in Inside Higher Education (highlighting an even more precipitous drop in History) showed how the number of Geography majors had also declined in the last six years, falling about 7 percent. No matter our research excellence, our success in procuring funding, our prominence in public discussion – if geography loses its majors, the field as a whole is in peril. This was a point expressed many years ago in Ron Abler’s classic column “Five Steps to Oblivion.” Ignoring majors is a sure-fire path to program destruction and, as we know full well, we can never take geography’s position in the curriculum for granted.

So should we be worried? We should at least be guarded. The trends of major loss in the last few years are real, but there are other countervailing forces on which geographers should capitalize.

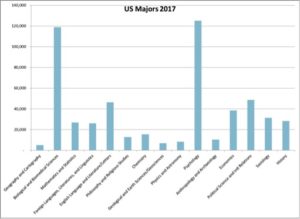

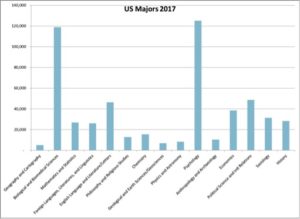

Compared to the other liberal arts, geography in the United States is a distinct underdog. We are the smallest of these traditional disciplines, just a bit under geology, physics and anthropology, and dwarfed by the likes of psychology and biology. Only 1 percent of all liberal arts majors specialize in geography. (By comparison, geography is squarely in the middle of the pack in the United Kingdom, comprising 5 percent of all liberal arts.) Geography has not been commonly taught in U.S. high schools. It is further hamstrung by its absence in most colleges and universities, relying on the larger state schools, some community colleges, a sprinkling of private colleges, and a very few private universities to provide the courses. Where geography is present, the departments tend to be small and most student majors arrive after their sophomore years.

Yet as a discipline, we punch far above our weight. Much of this is thanks to the AAG. Our membership of 12,500 rivals fields such as history, sociology, and political science. Our activities involve collaboration with geographers and other scientists around the world, many of whom look to American geography as a beacon, to the AAG as the one necessary organization, and to our annual meeting as the place to convene. About one-third of our membership is international, buoying our disciplinary footprint. Other strong organizations, like the American Geographical Society, the National Council for Geographic Education, and the Society of Women Geographers also help lay a foundation for geography outside the academy and in the schools.

A closer examination of the major numbers in the United States also shows that our recent decline may be a short-term phenomenon. Between 2007 and 2013, the number of geography majors grew 22 percent, and even with the decline in the last four years, we are still up nearly 10 percent over the last decade. But we may still look at how these recent trends could be reversed — a project that could involve seeing where the declines were sharpest and identifying possible areas of growth. (Liberal Arts as a whole has also suffered small declines). That we are in a better position in regard to majors than we were 11 years ago is a positive sign, but still worrisome.

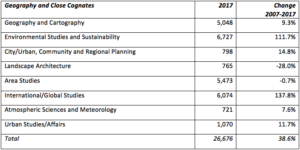

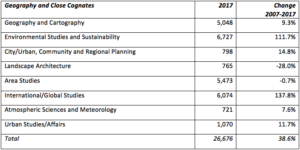

One very encouraging sign is in the expansion of some of geography’s closest cognates — fields like meteorology, environmental studies, area studies, and the like. These are fields commonly folded within geography departments and so almost always can count as a “geography” major. The table below shows the most important of these:

Pursuing such strategies entails the teaching of geography by other means. Students want geographical knowledge, they gain this by taking classes in these close cognates — often with geography professors — and they come out with much greater exposure to geography than would have otherwise been the case. Some of these incorporations may be acknowledged by renaming and Five Steps to Oblivion; other times the department may keep its name and just promote its diversity of offerings. To be sure, some of the traditional quasi-geographical specializations such as landscape architecture and area studies have declined. But there has been an explosion in environmental studies and global studies, with more modest growth in some of the other close cognates. If geography departments can capture those majors, the path toward sustainability becomes much clearer. At my department for instance, we were able to create an environmental studies major precisely because there was nothing like this available on campus. As a result, we have tripled our “geography” major numbers within the last two years. Other departments may pursue other strategies. Middle Tennessee State University, for instance, has a vibrant Global Studies major.

The last point I want to make also has potential to be the greatest opportunity. Since its inception, the Advanced Placement Human Geography high school course has exploded. Thanks to geographers like past President Alec Murphy, David Lanegran, and others, we were able to create this AP course in the 1990s and it has continued to defy all expectations. Out of the 38 AP exams given, AP Human Geography ranks in 10th place. (Environmental Science ranks 13th). The most striking aspect is its growth. Human Geography has grown by about 450% since 2008, far ahead of any other subject. And all signs indicate that this expansion will continue, as AP Human moves into other parts of the country.

Unfortunately, this phenomenal growth has yet to translate into major gains in college majors. AP courses/tests should make a positive difference in later specialization. Whether they just confirm existing intentions or open up new possibilities is still in question. But some worry that they end up eating into introductory course offerings. But there can be no doubt that this is a city-sized opportunity available to us. We need to devise ways as a discipline to turn these high school learners into college majors. The AP Human Geography exam and other AP possibilities will be the subject for a future column.

So despite some reason to worry, longer-term trends in the last decade are still positive, some of our closest cognates are growing briskly, and the expansion of AP Human Geography has been nothing short of phenomenal. The long-term health of the discipline is not assured, but it is within reach. We must exploit our advantages.

If you have gotten this far, let me extend my gratitude to all of you for giving me the chance to serve as president of the American Association of Geographers. I am humbled in succeeding people like Glen MacDonald, Derek Alderman, and Sheryl Luzzadder-Beach, not to mention all the luminaries who served before them. I look on these columns as an opportunity to shine light into some of the various features and problems of our discipline. Among these will be columns on creating a more inclusive academic culture, the internationalization of the AAG, the explosion of metrics in our discipline, publishing paradoxes, encouraging great writing, managing mental health, promoting opportunities beyond academia, and rethinking the regions. I hope that each column helps to further a dialogue, as there are rarely easy answers. We just need to keep trying. Please email me at dkaplan [at] kent [dot] edu with your thoughts.

— Dave

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0056

Source for this data comes from IPEDS Access Database for Integrated Postsecondary Education Data (IPEDS) Collection, https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds.

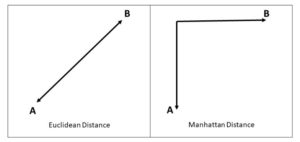

Savvy spatial thinkers recognized that the Euclidean distance calculation offered no insight into the actual distance one might travel along a road network to get to a destination, and they chose instead to employ the Manhattan distance calculation as a simulation. The method offered N–S or E–W movements in a stair-step pattern. While the resultant distance was likely more appropriate in most cases, there was no question that it was a substandard approach to calculating distance along a road network. Until recently, understanding access to care from the patient perspective has been a daunting technological challenge.

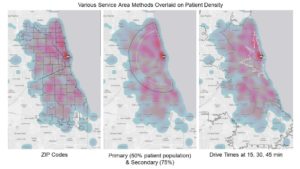

Savvy spatial thinkers recognized that the Euclidean distance calculation offered no insight into the actual distance one might travel along a road network to get to a destination, and they chose instead to employ the Manhattan distance calculation as a simulation. The method offered N–S or E–W movements in a stair-step pattern. While the resultant distance was likely more appropriate in most cases, there was no question that it was a substandard approach to calculating distance along a road network. Until recently, understanding access to care from the patient perspective has been a daunting technological challenge. Healthcare administrators have also been interested in the issue of access. The concept has broad implications for planning services, managing populations, and preventing hospital readmissions. Initial GIS methods for access calculations from this perspective included the use of buffers or pre-defined service regions. It’s a very simple prospect to drop a point representing a hospital and create a 10-mile circular buffer to represent an area of general accessibility to the facility. From the hospital perspective, this method is roughly equivalent to the Euclidean distance calculation.

Healthcare administrators have also been interested in the issue of access. The concept has broad implications for planning services, managing populations, and preventing hospital readmissions. Initial GIS methods for access calculations from this perspective included the use of buffers or pre-defined service regions. It’s a very simple prospect to drop a point representing a hospital and create a 10-mile circular buffer to represent an area of general accessibility to the facility. From the hospital perspective, this method is roughly equivalent to the Euclidean distance calculation. In 2000, Radke and Mu inspired the development of a method offering improved realism for accessibility called the two-step floating catchment area. The technique, derived from gravity models, attempts to capture several spatial variables and their interactions. The model requires the assessment of physician availability (supply) at locations (i.e., hospitals) as a ratio to their surrounding population (within a travel time threshold) and then sums those ratios around each residential (demand) location. Since its development, several enhancements have been made to the method that improve accuracy across different environments (like rural and urban). In 2011, a three-step floating catchment area technique was published that helped to minimize the overdemand estimation caused by the two-step method. The advance further refined the results, offering potential for better resource planning and identification of health professional shortage areas due to limited access.

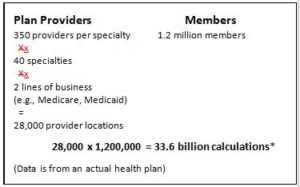

In 2000, Radke and Mu inspired the development of a method offering improved realism for accessibility called the two-step floating catchment area. The technique, derived from gravity models, attempts to capture several spatial variables and their interactions. The model requires the assessment of physician availability (supply) at locations (i.e., hospitals) as a ratio to their surrounding population (within a travel time threshold) and then sums those ratios around each residential (demand) location. Since its development, several enhancements have been made to the method that improve accuracy across different environments (like rural and urban). In 2011, a three-step floating catchment area technique was published that helped to minimize the overdemand estimation caused by the two-step method. The advance further refined the results, offering potential for better resource planning and identification of health professional shortage areas due to limited access. But what about going back to the patient perspective on the question of access to healthcare? There are now regulations in place that attempt to improve access to care by first understanding it from the patient’s perspective. I’m talking about network adequacy requirements, which refer to a health plan’s (including provider/plans) ability to deliver the benefits promised by providing reasonable access to a sufficient number of in-network primary care and specialty physicians, as well as all healthcare services included under the terms of the contract. Given the vast differences in topologies and road networks from one place to another, it makes sense that the regulation is based on driving times and driving distances together to formulate the most accurate picture possible. Depending on the regulatory agency, the standard for what is deemed an “adequate” size for a provider network will differ, but one important aspect remains the same. It is impossible to calculate the geographic network adequacy of a plan without the help of a GIS. Still, this is not a trivial matter when one considers the math involved. The number of calculations for this, from the individual perspective, is daunting, on the order of 34 billion for a medium-sized health plan.

But what about going back to the patient perspective on the question of access to healthcare? There are now regulations in place that attempt to improve access to care by first understanding it from the patient’s perspective. I’m talking about network adequacy requirements, which refer to a health plan’s (including provider/plans) ability to deliver the benefits promised by providing reasonable access to a sufficient number of in-network primary care and specialty physicians, as well as all healthcare services included under the terms of the contract. Given the vast differences in topologies and road networks from one place to another, it makes sense that the regulation is based on driving times and driving distances together to formulate the most accurate picture possible. Depending on the regulatory agency, the standard for what is deemed an “adequate” size for a provider network will differ, but one important aspect remains the same. It is impossible to calculate the geographic network adequacy of a plan without the help of a GIS. Still, this is not a trivial matter when one considers the math involved. The number of calculations for this, from the individual perspective, is daunting, on the order of 34 billion for a medium-sized health plan. As geographers, we all know the value of geography. Right? It is a field that provides a unique perspective, an appreciation for particularity, an opportunity to synthesize. But as much as we affirm geography’s value to each other, we also need to look at how geography is perceived outside of our community.

As geographers, we all know the value of geography. Right? It is a field that provides a unique perspective, an appreciation for particularity, an opportunity to synthesize. But as much as we affirm geography’s value to each other, we also need to look at how geography is perceived outside of our community.