The Bully Pulpit

I begin my first column by thanking you for electing me president of the AAG, a decision I hope you do not regret. I am simultaneously very excited and nervous about this opportunity but I know that I have excellent support from my in-house colleague, Bob Bednarz, from Doug Richardson and a terrific staff at Meridian Place, and from a superlative Council. And I will lean on the wisdom of many Past Presidents who guide me, notably Julie Winkler, Mona Domosh, Dick Marston, Alec Murphy, and Ken Foote.

I begin my first column by thanking you for electing me president of the AAG, a decision I hope you do not regret. I am simultaneously very excited and nervous about this opportunity but I know that I have excellent support from my in-house colleague, Bob Bednarz, from Doug Richardson and a terrific staff at Meridian Place, and from a superlative Council. And I will lean on the wisdom of many Past Presidents who guide me, notably Julie Winkler, Mona Domosh, Dick Marston, Alec Murphy, and Ken Foote.

I now have the bully pulpit. Theodore Roosevelt coined this phrase at a time when bully meant something quite different from today. To TR, everything good was bully. But its current meaning of speaking from a point of authority, of being a little bossy, or pedantically instructive attracts me to the term. I hope to be more instructive than bossy; I know you will let me know if I am achieving this tone by commenting on my columns.

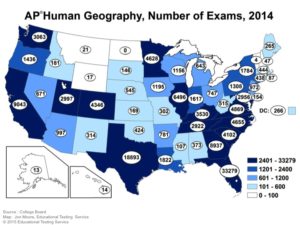

Earlier this month when I began to think about the content for this column I was in Cincinnati with 660 geography teachers and college and university faculty reading Advanced Placement Human Geography (APHG) exams. In Advanced Placement (AP) language, the people who evaluate the written portion of the test are called readers. The multiple choice questions are machine scored, but it takes many skilled professionals to assess the three brief constructed responses students write. This year more than 162,000 students took the introductory human geography class and exam; the distribution of those test takers is an interesting geography as shown on the accompanying map. Of that group, more than half (53.8%) received a score of 3, 4, or 5, the marks needed to qualify for college credit.

Earlier this month when I began to think about the content for this column I was in Cincinnati with 660 geography teachers and college and university faculty reading Advanced Placement Human Geography (APHG) exams. In Advanced Placement (AP) language, the people who evaluate the written portion of the test are called readers. The multiple choice questions are machine scored, but it takes many skilled professionals to assess the three brief constructed responses students write. This year more than 162,000 students took the introductory human geography class and exam; the distribution of those test takers is an interesting geography as shown on the accompanying map. Of that group, more than half (53.8%) received a score of 3, 4, or 5, the marks needed to qualify for college credit.

The Advanced Placement (AP) program is considered the gold standard of American high school education. According to conventional wisdom, taking an AP course affords students with myriad opportunities: experience in an academically rigorous class; an enhanced grade point average essential for college admission; college credit if successful in the examination; access to the best teachers; and preparation for college. Taking AP classes is prestigious for students just as teaching them is for teachers. A number of highly qualified high school teachers have become avid geographers through teaching the class. APHG has become a cornerstone of geography education and offers us a large and vibrant high school presence.

Criticisms of the AP program abound, focusing largely on student learning, rigor, access, and curriculum. One sweeping claim made for AP is that it prepares students for success in college. There is no evidence to support that assertion; simply taking an AP course does not guarantee college readiness or preparation to perform at a college academic level. However, a recent study conducted by independent researchers did find that students who received college-credit for AP exams (typically a score of a 3, 4, or 5) were more likely to complete their college degrees on time. In terms of rigor, it must be remembered that AP programs across subjects are not uniform, despite some effort on the part of College Board, the organization that sponsors AP, to audit course syllabi. Teachers are often assigned to teach an AP course without adequate academic preparation. And professional development in AP subjects is limited. Thus, there is tremendous range in the nature of AP courses. Simply having a “rigorous” course outline does not mean that the class will match it. This is compounded by concerns that the courses to many teachers are largely about test preparation and sometimes not about deep learning for understanding and transfer.

With regard to access, the AP program has seen phenomenal growth in the last 15 years, largely because AP is being used as a strategy to increase the quality of instruction in high schools. Schools everywhere are being urged to offer AP classes; what was once an opportunity only for wealthy suburban students is now an opportunity for urban students as well. This has led to growth in the numbers of African American and Hispanic AP students; from 2013 to 2014 there was a seven percent increase in traditionally underrepresented students taking an AP exam. Yet, gaps exist in both participation and performance on the tests, serious concerns, particularly to College Board.

Nonetheless, while geography as a discipline is finding new strength and vigor through interdisciplinary research, growing interest in things spatial, the geospatial revolution, and by its ability to address significant global issues in meaningful and generative ways, the discipline faces challenges to maintain its unique and singular identity. We need to grow, to capture new young minds, from across our diverse population. In the last five years, more than 230,000 students scored well enough to be eligible to receive college credit for introductory human geography. They have been supervised and coached by a large and growing number of teachers, most of whom are coming to geography as converts, not college majors. I urge us to reach out to APHG teachers and their classes. About a fifth of students who take APHG indicate they are interested in taking another geography course in college. Some are your future geography majors. Adopt them; nurture them; use them as your pipeline to your majors; engage your senior majors to mentor AP students. You will find that you learn a lot about innovative teaching from interacting with APHG teachers and they can hone their geographic perspective by talking with you.

Thanks, and I look forward to your comments. Really.