By Mike DeVivo

Grand Rapids Community College

Often underemphasized in higher education is the important role played by community colleges, which continue to be responsible for the education of 38% of all American undergraduates enrolled in public colleges and universities. Although David Kaplan’s presidential address and the AAG strategic plan have accentuated their importance, two-year institutions largely remain an untapped resource for our discipline. Enlisting community college faculty as fellow partisans engaged in the fight to keep geography as an imperative discipline on the higher education landscape has merit, for enrollment declines have occurred across the U.S. and geography programs remain at risk of termination; in many regional institutions, which nationwide have seen a 4% drop in enrollment during the past decade, this is a critical issue. Moreover, community colleges do much in contributing to the mission of advancing justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Often underemphasized in higher education is the important role played by community colleges, which continue to be responsible for the education of 38% of all American undergraduates enrolled in public colleges and universities. Although David Kaplan’s presidential address and the AAG strategic plan have accentuated their importance, two-year institutions largely remain an untapped resource for our discipline. Enlisting community college faculty as fellow partisans engaged in the fight to keep geography as an imperative discipline on the higher education landscape has merit, for enrollment declines have occurred across the U.S. and geography programs remain at risk of termination; in many regional institutions, which nationwide have seen a 4% drop in enrollment during the past decade, this is a critical issue. Moreover, community colleges do much in contributing to the mission of advancing justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion.

The demographic attributes of community college students contrast sharply with those in traditional institutions of higher learning; 30% are first generation, 16% are single parents, 5% are veterans, and 21% have disabilities. In terms of undergraduate underrepresented populations overall, community colleges enroll 52% of Native Americans, 48% of Hispanics, 39% of Blacks, and 34% of Asian Pacific Islanders. For a majority of community college students, working one or two jobs while pursuing studies is a way of life.

Community college transfer students make up 20% of the overall undergraduate enrollment in public four-year institutions; in California, it is 25%, and in Florida, it is 33%. Once community college students have transferred to four-year institutions, their retention rate of 81% is higher than that of other transfer students, as well as those who began as freshmen; 68% of associate degree recipients are awarded bachelor’s degrees within four years of entering their selected transfer institution.

Although the average student in a two-year institution is 28 years of age, community colleges are also responsible for the education of many high school students; 34% of secondary school students complete college courses prior to their high school graduation. The number taking geography courses at community colleges is not small, and their interest in pursuing geography as a major at four-year institutions is growing. Certainly, their exposure to the discipline contributes to an expansion of geography majors in transfer institutions, as does the exposure of our field to the non-traditional students making up the lion’s share of enrollment in community colleges.

Non-traditional students are increasing in importance as traditionally aged college students are declining. The National Center for Education Statistics has forecasted a 2.1% decrease in high school student enrollment between 2020 and 2030; further declines are likely in the following decade. Geography programs in both two-year and four-year institutions stand to benefit much from establishing close partnerships, which is likely to increase undergraduate enrollments in each; but it is more than just a numbers game. Expanding the presence of geography enhances opportunities to diversify the discipline, demonstrate its value to society, and educate knowledgeable public citizens. As the onus of responsibility in building these relationships must be placed equally upon the shoulders of the faculty at both two-year and four-year institutions, discussed below are some prudent considerations.

General Education and Transfer. Geography can play an important part in the general education curricula of the institutions in which the discipline persists, for unlike most disciplines, geography courses can be listed among those meeting Social Sciences, Natural Sciences, and Diversity requirements. Moreover, general education course enrollments often validate the presence of geography programs and provide opportunities for attracting majors. Expanding the number of general education geography courses at four-year institutions increases the discipline’s exposure, and developing corresponding courses at two-year institutions does the same. Ensuring their transferability is imperative.

Distance Education. Enhancing distance education at both community colleges and their corresponding transfer institutions is a must; creation of online, hybrid, and short-term residency courses can accommodate student needs. More than 40% of community college students complete most of their coursework online, and for some it is a necessity; 12% do not have the means to commute to the classroom and 9% must care for a family member. As bachelor’s degree distance education programs in geography are limited, developing affordable options to meet the needs of community college transfer students brings considerable benefit to the discipline.

Teaching and Mentoring. Not only is interactive engagement expected, but teaching and mentoring are also attributes that enhance learning, such as empathy, understanding, and compassion. Likely, most college students are characterized by three or more adverse childhood experiences, which can markedly affect academic performance. Faculty are tasked with adopting some level of flexibility while also maintaining academic rigor. By establishing mutually respectful academic relationships, geography faculty in community colleges can assist promising students to gain awareness of the opportunities the discipline has to offer, which should not only include entry-level employment prospects, but also graduate school assistantships and fellowships. Of course, collaboration with transfer institutions does much to facilitate success.

GTU & VGSP. As one of the few honor societies endorsed by the Association of College Honor Societies that charters chapters in community colleges, Gamma Theta Upsilon’s presence can play a role in elevating the status of geography. A GTU chapter not only enhances the visibility of the discipline, it provides students a forum in which they can plan conference presentations, raise funds for travel, and make contributions to the local community, such as spearheading food drives for children in poverty, and engaging in service in other ways. Moreover, the Visiting Geographical Scientist Program, administered by the AAG and funded by GTU, provides an opportunity for faculty and students in two-year and four-year institutions to collaborate in co-hosting visiting speakers. These kinds of partnerships can be effective in recruitment of majors and showcasing geography to administrative leaders and members of the public. As two-year institutions tend to have close ties to local communities, community college geographers can play an important role in facilitating the town and gown relationships with geography faculty in local four-year institutions.

Academic Conferences. Annual meetings of the AAG in addition to those of its regional divisions, and state geographical societies (e.g., California Geographical Society) provide opportunities for faculty and students from academic institutions of all types to confer, present their research, and engage in the relationship-building that contributes to the success of academic geography.

Indeed, the AAG plays a critical role here, for among other things, elevating the discipline tasks the organization’s leadership to elevate the status of regional division annual meetings. Moreover, the organization must demonstrate both vitality and value to all academic geographers, many of whom have been on the hinterlands of American higher education for years. Urgent action is needed to address some of the 21st century changes in higher education that can adversely impact academic geography and the “health” of departments.” Developing community college-university alliances will not resolve all—or even most—issues facing geography programs; but these kinds of partnerships carry the potential to do a lot in the shaping of healthy departments.

References

American Association of Geographers. 2023. AAG Strategic Plan: 2023-2025. Washington, DC: American Association of Geographers.

American Association of Geographers. 2022. The State of Geography. Washington, DC: American Association of Geographers.

American Association of Community Colleges. 2023. Fast Facts 2023.

Brenan, M. 2023. Americans’ Confidence in Higher Education Down Sharply. Gallup (11 July).

Fry, R & Cilluffo, A. 2019. A Rising Share of undergraduates are from Poor Families, Especially at Less Selective Colleges. Pew Research Center (May).

Gardner, L. 2023. Regional Public Colleges are Affordable—but is that enough to draw students? The Chronicle of Higher Education: 28 July.

Kaplan, D. 2023. Who Are We? Redefining the Academic Community. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 113 (8): 2003-2012.

National Center for Education Statistics. 2024. Digest of Education Statistics, 2022. Washington, DC: US Department of Education.

Velasco, T. et al. 2024a. Tracking Transfer: Community College Effectiveness in Broadening Bachelor’s Degree Attainment. New York: Community College Research Center.

Velasco, T. et al. 2024b. Tracking Transfer: Four-Year Institutional Effectiveness in Broadening Bachelor’s Degree Attainment. New York: Community College Research Center.

The Healthy Departments Committee provides engaged guidance and action that enhances the future health and excellence of academic geography departments across the country. Take advantage of our resources and get your voice heard.

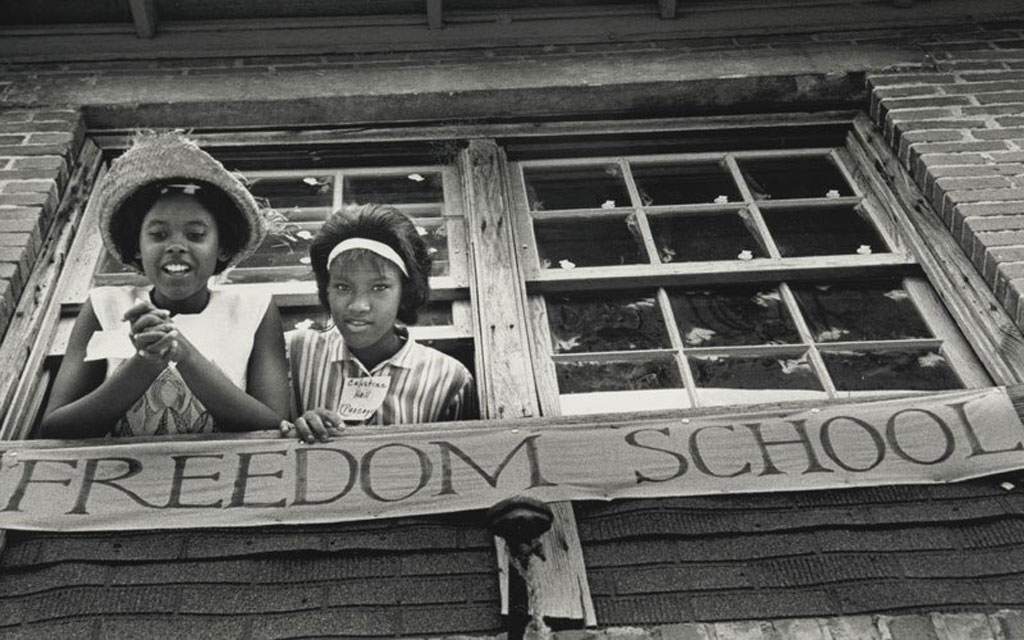

The 60th anniversary of

The 60th anniversary of

Often underemphasized in higher education is the important role played by community colleges, which continue to be responsible for the education of 38% of all American undergraduates enrolled in public colleges and universities. Although

Often underemphasized in higher education is the important role played by community colleges, which continue to be responsible for the education of 38% of all American undergraduates enrolled in public colleges and universities. Although