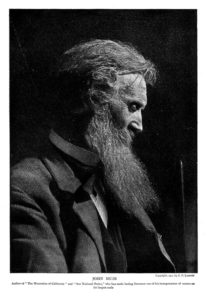

William Garrison

Bill Garrison, one of the leaders of geography’s “quantitative revolution” in the 1950s and an outstanding transportation geographer, passed away on February 1, 2015, at the age of 90.

William Louis Garrison was born in April 1924 and raised in Tennessee. During the Second World War he did meteorological work for the US Army. He received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Peabody College in Nashville and a doctorate in geography from Northwestern University.

In 1950 Garrison moved to the University of Washington and, as a young faculty member, led the way in revitalizing the field of geography through the use of scientific methods. In particular, he came up with the idea of using of statistics and computers to study and better understand spatial problems. Thus began an immensely exciting and important period in the history of geography, the so-called “quantitative revolution.”

Under Garrison’s supervision at the University of Washington were a number of doctoral students who were also interested in scientific approaches to spatial problems. They included Brian Berry, William Bunge, Michael Dacey, Arthur Getis, Duane Marble, Richard Morrill, John Nystuen and Waldo Tobler, and were dubbed the “space cadets.” Starting with computing systems such as the IBM 604 and IBM 650 they went on to be instrumental in the evolution of geographic information systems.

In 1960 Garrison moved to Northwestern University and subsequently had stints at University of Pennsylvania, University of Illinois and University of Pittsburgh, before moving to University of California, Berkeley in 1973 as a Professor in the Civil Engineering Department.

By this time Garrison’s interests had shifted to transportation. His work at Berkeley focused on how innovation and technological change occurs in large transportation systems. This included an interest in alternative vehicles and the future of the car. He was genuinely able to ‘think outside the box’ in envisioning a better and more efficient transportation future; for example, he organized the first ever U.S. conference on Intelligent Vehicle-Highway Systems.

Garrison made invaluable contributions to the Transportation Engineering Program in the department, expanding and strengthening the planning and policy elements of the curriculum. From 1973 to 1980 he was also Director of the university’s Institute of Transportation and Traffic Engineering (later renamed the Institute of Transportation Studies). During his tenure he set out to broaden its scope beyond transportation and traffic engineering. He believed in the value of interdisciplinary work and drew in colleagues from the departments of City and Regional Planning, Economics, Geography, Public Policy and Sociology.

He served on numerous national committees advising the Bureau of Public Roads, Department of Transportation, Department of Commerce, and Bureau of the Census, as well as the National Science Foundation, National Science Board, and National Research Council. He also served as consultant to non-profit and business organizations, and had a stint as Chairman of the Transportation Research Board.

Garrison retired from UC Berkeley in 1991 as Professor Emeritus of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Emeritus Research Engineer in the Institute of Transportation Studies but that was by no means the end of his academic career. Post-retirement publications included the book Tomorrow’s Transportation: Changing Cities, Economies, and Lives with Jerry Ward (2000), the report Historical Transportation Development (2003), and two editions of the book The Transportation Experience: Policy, Planning, and Deployment with David Levinson (2005, 2014) which drew on his work in Austria examining the growth trajectories of various transportation technologies.

Garrison was a long-time member of the AAG, having joined in January 1947. His early contributions to the discipline were recognized in 1960 with an award for Meritorious Contributions in the annual honors. In 1994 two of the AAG Specialty Groups also bestowed their highest honors upon him for his outstanding contributions: the Edward L. Ullman Award from the Transportation Geography Specialty Group and the James R. Anderson Medal from the Applied Geography Specialty Group. Beyond the AAG he received the Roy W. Crum Award from Transportation Research Board in 1976 and the Award for Distinguished Contribution to University Transportation from the Council of University Transportation Centers in 1998. In 2000, his “space cadets” reunited to honor his 50 years of inspirational leadership in geographical and transportation sciences.

An AAG award was also established in his name. The biennial William L. Garrison Award for Best Dissertation in Computational Geography aims to encourage students to use advanced computation for resolving the complex problems of space–time analysis that are at the core of geographic science.

Garrison was one of the most important geographers of the twentieth century. When introducing him as the speaker at the 2007 Anderson Distinguished Lecture in Applied Geography, Ross Mackinnon described him as “a true ‘Mount Rushmore’ figure in modern American geography.”

Bill is survived by his wife Marcia and their four children, Deborah, James, Jane and John; his three children from his first wife Mary (who predeceased him), Sara, Ann and Helen; as well as 16 grandchildren, and one great grandchild.

Further reading

Barnes T. J. (2001) “Lives lived and lives told: biographies of geography’s quantitative revolution” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 19 (4) 409–429

Garrison, W. L. (2002) “Lessons From the Design of a Life” in Peter Gould and Forrest R. Pitts (eds.) Geographical Voices: Fourteen Autobiographical Essays Syracuse University Press

DeVivo, M. S. (2014) Leadership in American Academic Geography: The Twentieth Century Lexington Books