The Hills of San Francisco

Unlike the rest of California, San Francisco has a unique geography that shapes its weather and settlement patterns. The city is set on the tip of a peninsula halfway up the coast of northern California, surrounded by bodies of water on three of its sides: the Pacific Ocean, the Golden Gate strait, and the San Francisco Bay. The city is laid out over hills that stretch from coast to coast, reaching heights of nearly 1,000 feet, making the climate similar to coastal areas on the Mediterranean.

The hills of San Francisco define its topography and culture. It’s hard to pinpoint the exact number in the city, but many sources consider there to be more than 50 named hills. As Pulitzer Prize-winning San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen notes in his introduction to the Hills of San Francisco, no one can quite agree on which [hills]. Although it’s debated among locals, there are seven hills that are iconic to the city: Russian Hill, Nob Hill, Telegraph Hill, Twin Peaks, Mount Davidson, Mount Sutro, and Rincon Hill.

So, when is a hill a hill? Self-proclaimed San Francisco explorer Dave Schweisguth claims, “When it’s a lone mountain. That is, if you can walk all the way around it, always looking up to its summit. It’s not so clear cut when hills run together into a ridge, which most of San Francisco’s do. Height alone is not so important: a very small hill may be perfectly obvious, while a string of higher summits may be hard to tell one from the next. It’s easier to call a hill a hill if it’s separated from its neighbors — if, on a topographic map, a contour line or two traces all the way around its summit.”

The Range of Iconography

Originally named Blue Mountain for the wildflowers that cover the hillside, the city’s tallest hill was renamed Mt. Davidson at the urging of the Sierra Club in 1911, after George Davidson, the geographer who surveyed it. It is the focal point of San Francisco’s Mt. Davidson Park, with a forest that accounts for more than 30 of the park’s acres, quietly remaining an oasis in the most densely settled city in California. Defined by a 100-foot cross at its peak, Mount Davidson stands at an elevation of 928 feet. Urban hikers share that despite how small the overall area is, the trails aren’t consistently marked, which causes explorers to get lost in the woods.

Hikers also recommend Mount Sutro, located in central San Francisco, for its role in the city’s cultural and natural history. Its century-old trails are now preserved by the University of California, San Francisco, which guides the long-term restoration of the 61 acres and protects the ecological oasis in the heart of the urban environment, along with the citizen group Sutro Stewards. The city’s elevation and abundant summer fog contribute to the mountain’s microclimates and its plant and wildlife communities.

Originally called “Los Pechos de la Choca” (Breasts of the Maiden) by early Spanish settlers, Twin Peaks is a main landmark of San Francisco’s skyline, reaching elevations of 910 and 922 feet. Similar to Mt. Davidson and Mt. Sutro, Twin Peaks hosts a 64-acre park of coastal scrub and grassland communities that offer an idea of how San Francisco’s hills and peaks looked before development changed them forever.

Early in defining San Francisco’s history, Nob Hill, Russian Hill and Telegraph Hill continue to remain among the most popular neighborhoods to visit.

Russian Hill’s name dates to 1847 when Russian sailors were buried on the hill during the gold rush in the 1800s. The burial sites are long since deeply covered, and it’s now only possible to admire a plaque at the site where the cemetery once stood. This is the same neighborhood home to the famous Lombard Street, that draws tourists from around the world due to its scenic switchbacks and postcard views. Because the slope in this area reaches 27° (51%), 8 hairpin bends were put in the 1300 feet between Hyde Street and Leavenworth Street to allow cars to drive down the street, ultimately creating one of the most winding streets in the world.

Russian Hill borders Nob Hill to the south, one of the city’s most upscale neighborhoods. Originally called California Hill (after California Avenue, which runs right over it), Nob Hill got its name from the word “nabob” that originated from the Hindu word meaning a wealthy or powerful person. This affluent neighborhood was home to the Central Pacific Railroad tycoons known as the “Big Four,” who were among the first to build their mansions here.

Telegraph Hill hosts Coit Tower, an iconic piece of architecture that resembles a fire hose and affords incredible views of the city; its walls are also home to historic artwork. Originally, the Tower was a windmill-like structure created in 1849 to signal ships entering the Golden Gate. Once the trek is completed, the summit provides a breathtaking panoramic view of the city with landmarks like the Golden Gate Bridge, Alcatraz, and the Transamerica Pyramid.

Whether you’re taking a leisurely stroll or hiking the steepest routes, you can recall the words of the iconic San Francisco journalist Herb Caen, who once said, “Take anything from us — our cable cars, our bridges, even our Bay — but leave us our hills.”

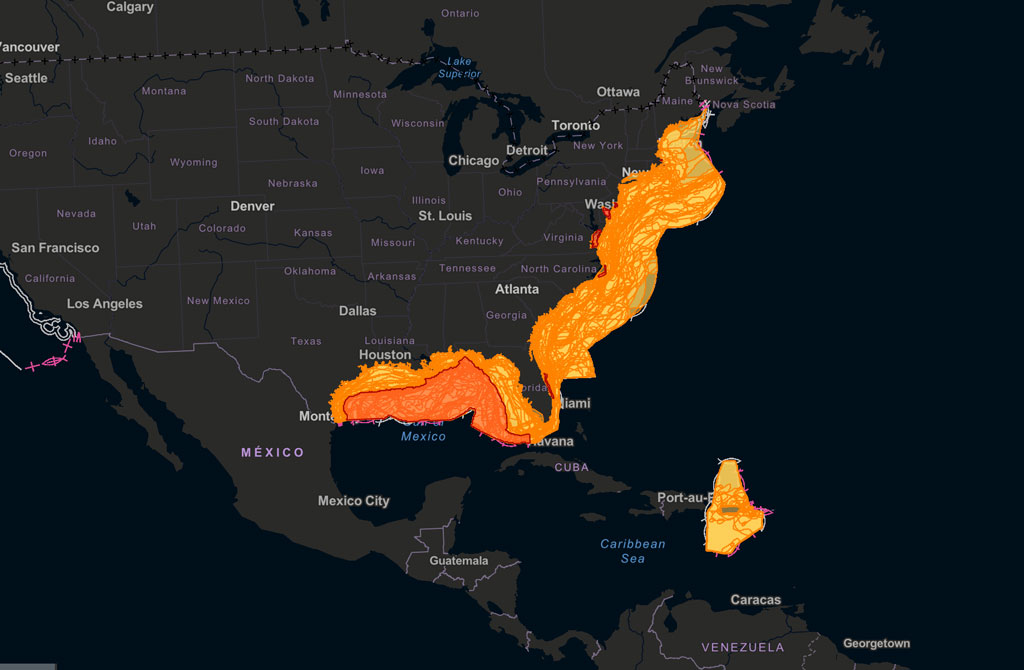

You can hit the trails with a guided tour or explore the city on your own. The SF Gate compiled a list of 11 hikes within the city limits that allow visitors and residents to get to know the landscape. An interactive map created by a UC Berkeley graduate student studying urban planning maps SF’s slopes and uses simple color coding to show where the flattest pockets of land are. If you’ll be attending AAG’s 2026 Annual Meeting in San Francisco, you’ll want to bring your walking shoes!

Geography in the News is an educational series offered by the American Association of Geographers for teachers and students in all subjects. We include vocabulary, discussion, and assignment ideas at the end of each article.

Geography in the News is an educational series offered by the American Association of Geographers for teachers and students in all subjects. We include vocabulary, discussion, and assignment ideas at the end of each article.