Education: MS in Geographic Information Science (San Diego State University), BS in Architecture (University of Colorado Denver)

The following profile was compiled by Jessica Embury (San Diego State University) for the Encoding Geography initiative. To learn more, visit: https://www.ncrge.org/encoding-geography/

Please describe your job, employer, and the primary tasks that you perform in your position.

I am currently a GIS web developer for a mid-sized engineering firm of about 600 people that has offices in Minnesota, Texas, and Colorado. My primary tasks are geospatial scripting for various locations and tracking different types of assets, like cranes and street sweepers. I also work on web mapping applications that are generally used by cities and counties to manage tax data, parcel data, or stormwater information. I work on other applications for the oil and gas industry, like helping manage location audits and tracking different types of surveys on job sites throughout Texas.

Previously, I’ve worked on EPA projects, like a common operating picture, which was essentially an emergency response platform. It had various assets and information brought into it regarding wildfires and other things. I’ve also worked on geospatial scripting for generating time enabled smoke imagery mosaics where I took cams and files from the Forest Service’s Blue Sky platform and translated that into a time enabled hosted and managed service.

Other projects I’ve worked on were Native American tribal nations software, like central data management systems for managing water quality, collecting surveys from research scientists, and managing environmental cleanup.

What is your educational background? How did you initially discover geocomputation and why did you ultimately choose a career that uses geography and computer science?

My bachelor’s degree is in architecture and that’s where I was first introduced to GIS, in a natural hazards course. It’s how I got interested in wildfires and learning about GIS and what I could do with it. I also took an architectural cartography course which covered using GIS data to visualize changes in Denver, where I went to school.

After working in architecture for a couple years, I just didn’t enjoy it and I always loved geography so I was hoping I could use some of my experience regarding planning, knowledge of fire, and building codes and somehow apply GIS to work with wildfires. Then, I completed my masters at San Diego State University and did my thesis on geovisualization and descriptive analysis of landscape level wildfire behavior using repeat pass airborne thermal imagery.

During that time, I developed web applications for visualizing different attributes of landscapes and wildfire behaviors, such as reduced spread. I also did a descriptive analysis and worked on a couple other projects using GIS.

I ultimately chose a career in geocomputation because I really liked the programming side of it. I thought it was an interesting and powerful skill set for being able to work with GIS data that not a lot of people have. I felt it also helped to have programming skills when I graduated and got into the job market.

Is GIS usage widespread in architecture education and the industry?

No, it is primarily used by planners but not really in architecture. If you work with site plans for master planning communities then you might get a little more experience. I worked in multifamily architecture so I got some experience using GIS to edit line work for a community master plan in Colorado, but that was the extent of it. Most architects I’ve met never use GIS. They do a lot of 3D modeling and data information modeling, but that’s about it.

When you think about geography, what specific background knowledge and conceptual ideas are important and useful to know?

Something that I feel is really under-represented in geographic education is learning how to work with coordinate systems and geographic versus projected coordinate systems. I run into a lot of issues in my job where people aren’t familiar with those concepts and then they don’t understand why certain tools aren’t working or what data processes are happening.

Working with different data types and understanding how a database is structured is really helpful, but that’s more specific to a development role. Also, being familiar with common tools and processes for editing vector data and evaluating the accuracy of GPS data. I think having familiarity with GIS and data standards are the most important for a geospatial developer.

When thinking about computer science, what specific background knowledge and conceptual ideas do you think are important and useful to know?

For a web GIS developer, understanding how websites work is important, like what happens when you type in a URL and how data is tasked between different services. For example, if you have a GIS server instance, how do you get data from that? A broad level of knowing how a REST API works is really important and critical for using geospatial data in websites. Also, having a general understanding of relational databases and becoming comfortable with certain programming languages are big skills.

What procedural knowledge do you think is important and useful to know, from either geography or computer science?

From geography, or the computer science side of geography, I think it’s really important to be familiar with Esri products like ArcGIS Pro or ArcDesktop, because those are widely used, especially in cities and municipalities. Then, understanding what Esri portal and enterprise are and how to use ArcGIS Online. Even as a developer, I use those tools all the time.

Getting a little more into the computer science part, it is important to know how to use ArcPy and the ArcGIS Python API, as well as open source software. I haven’t used QGIS recently but I think that’s a good one to learn if you don’t have access to other GIS. Then, being familiar with libraries such as GDAL and OGR for Python is really helpful. Also, knowing how to set up a PostGIS database is a specific skill that’s really helpful for the computer science part. I mainly work with Javascript, Typescript, Python, a little bit of C# (C-Sharp).

With web development, I also use HTML and CSS. If you’re going to be a web developer, you need to know the basics of vanilla JavaScript, which is what they call using JavaScript without a framework. Understanding how to make a call to a REST endpoint and how to get data from a host or feature service is really important. Generally understanding the life cycle, like a promise in JavaScript is important, so if you get data you’re leaving that response. Then understanding the DOM, the document object model, and how that works. Essentially, how is an html page structured and then, depending on what resources you use, knowing a rest API and how that works. You could also look into a soap API which uses xml. I did run into that a little bit, especially larger scale stuff. We essentially had a big repository for data that was used by Federal Government employees and now it’s translated from xml. So that’s the specific programs stuff.

Then, for Python, you should know some of the big geospatial libraries and know when it’s appropriate to use certain things and that just takes time. Then, if you want to get a job, it’s helpful to know a framework and have something that you’ve built, have examples of work that you’ve done, no matter how small they are, but have examples of a small portfolio and if you can explain what’s happening behind the scenes – then that’s pretty critical to getting a job in the field.

What is an example of a social, economic, environmental or other issue that you recently investigated in a project at work?

We work mostly with environmental issues. I’m currently working on a stormwater asset management program so it uses some hydrological modeling that’s above my head, but essentially it’s a program which can forecast when stormwater basins and ponds will need maintenance, so preserving stormwater ponds in different communities throughout Minnesota.

Another project I worked on is the EPA common operating picture, and for that I worked on a few different widgets and a web map and one of them, for environmental data, was that smoke mosaic data. We set up a script to run every 24 hours and update daily [to] provide information on particle density for smoke over California, Nevada, and a couple other states in the southwest US. Another component of that was tracking active fire perimeters and if there were active fire parameters within 10 miles of an EPA facility, [then] that would notify people.

What kind of geographic or computational questions did you ask and think about during your project?

I’ll talk about the smoke data because that’s really interconnected with air quality, which can be interconnected to a lot of other social and environmental issues related to people who are disproportionately affected by that. The question is, from a technical standpoint, how do we transform these cams and the files into something that’s useful and time-enabled? Then, how do we convey that knowledge to somebody who doesn’t have a GIS background? And how can we make it useful at the scale? So the scale of this data is multiple states, the lower 48 states of the contiguous U.S..

Knowing how to resample that imagery was important, so how do we make sure that it’s an appropriate scale and spatial resolution for the task at hand? Then, that kind of blended into programming, so this would be kind of a classic geospatial scripting – You’re transforming the data, so you first need to get the data, so you make a request to that site and get the data, unzip it, then you need to organize it. For that dataset we had times in each image file name, so you could just use Python to pull out the dates, and then you need to transform it into the correct projection. You need to reproject those rasters and then, once you do that, you can look at the different types of resampling that you can do. Then, once you have all your data finished and you finished the processing of your data, you then need to work on the final product. So you kind of have these iterative steps to clean the data, get it in a format you want, and make sure it’s displaying correctly at an appropriate spatial resolution or appropriate coordinate system.

And then, once that’s done, you can do the final task, which is essentially creating an image service that you can just put in a web app that has time enabled on it, which is an Esri specific thing, because if you enable time on this image layer, then you can use all these different filtering tools to visualize the data.

What types of data did you acquire to support your project? If possible, please identify up to three data sets you utilize the most.

So we used the BlueSky daily runs from the WebSky platform from the United States Forest Service, which is a research model that they generate for different regions in the U.S..

https://tools.airfire.org/websky/v2/#status

For the EPA, we used a couple different datasets. I don’t know how much I can talk about that, but we did use the classic U.S. main fire perimeter data: the NIFC current wildfire perimeters data set. Currently, we use a lot of parcel tax data, so that’s more specific to city and county level, but I would say we work with that the most.

What type of content knowledge and skills did you use to evaluate, process, and analyze the data that you gathered for your project?

For the remote sensing part of that project, it was about understanding the different types of interpolation, such as nearest neighbor, and resampling methods for raster data. Also, being able to identify your destination coordinate system and apply any projections that you need.

Content knowledge and skills specifically for programming would be understanding how to use Open Source geoproducts, so in that case it was GDAL to work with raster data. Then principles for more general types of skills like Python programming and using Jupyter notebooks or ArcGIS notebooks to schedule a task to run every 24 hours to get new data and republish the image service.

As a developer, I get a lot of hard skills but the soft skills can be ignored a little bit. The most important thing I’ve learned is being able to explain to somebody why something is important if they don’t have a background in GIS and being able to distill the work you’re doing and provide a high level summary. That’s something we have to do all the time. An example of this would be when I built a continuous integration continuous development pipeline for a client. What this does is it builds their application tests and it deploys it to wherever they want automatically. So I had to be able to distill this really technical process of backing up and restoring databases and running certain types of integration tests to a client that doesn’t really have a strong computer science background and I’m just a GIS technician. That was for a Tribal Nations organization. So how you distill that knowledge upwards and explain what you’re doing and why it’s meaningful is the most important part of this process.

How did you apply geography and computer science to communicate the results of your project? Do you have a recent product or publication that you can share as an example?

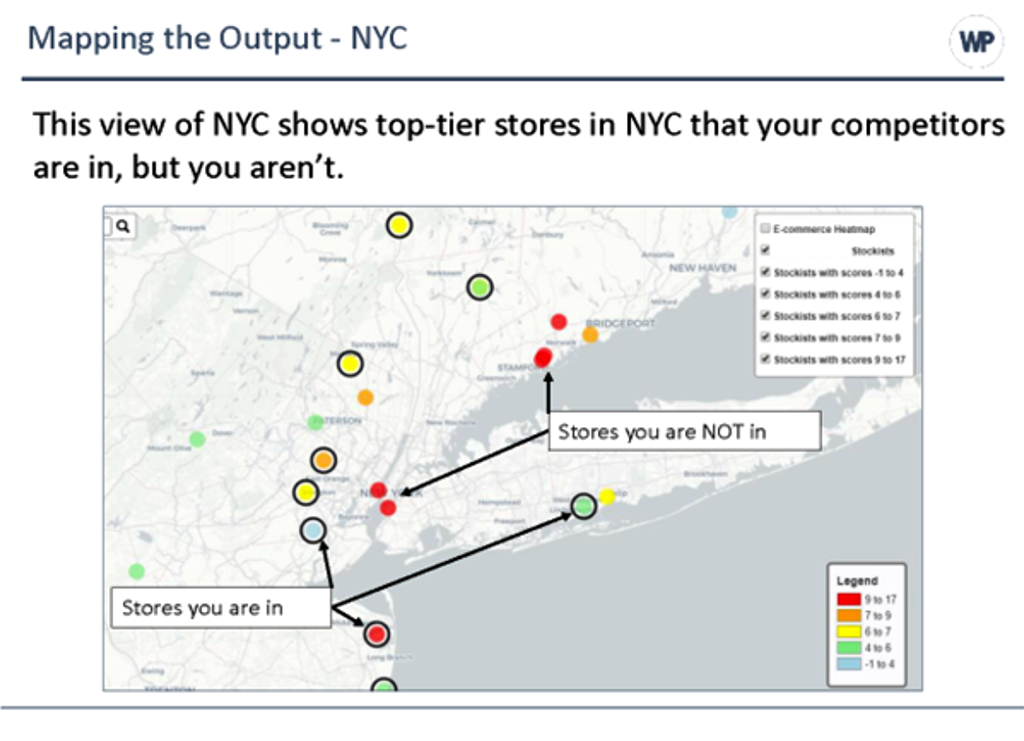

I primarily use web applications. I don’t usually use maps very often, unless they’re embedded in a web application. So I do a lot of mapping applications where geovisualization is an important part of that.

How to display data in a meaningful way is always important, even at city levels, if they have huge data sets, like a lot of utility data sets and storm water and sewer and parcel. A lot of them have tons of data, so how do you display that data in a way that doesn’t get super cluttered or confusing?

For a recent product, we have a public facing web page. This is another product for oil and gas. There is a video on this website that does a little walkthrough:

https://www.wsbeng.com/expertise/technology/solutions/datafi/

WSB Engineering and Innovate! Inc. are the two companies I’ve worked for. I wanted to work in-person. I think it is important to have that in-person mentorship as a developer.

Reflecting on your work, how does it align with your personal values and your community or civic interests?

I’ve been able to explore some environmental issues that generally align well with my personal values. I feel like I get to make a positive impact, and even with fields and sectors of oil and gas that I wouldn’t necessarily see myself working in, I like that I get to help with environmental compliance and making sure that field workers are safe and sticking to appropriate procedures.

I really enjoyed the work I did for the Environmental Protection Agency. That’s probably been the highlight so far – being able to work for an agency that I admire. Being able to work with the Forest Service is great too. Most of my work is related to environmental issues, which I’m passionate about, but it would also be great to use this data for other civic or social justice projects to see how GIS data can be useful for that.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grants No. 2031418, 2031407, and 2031380 (Collaborative Research: Encoding Geography – Scaling up an RPP to achieve inclusive geocomputational education). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation

Bill spent 43 years at UWGB as a Professor of Geography and Department Chair, and postponed retirement to fill the position of Interim Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs. For decades, he hosted the Bill Laatsch Wine and Cheese Classic each fall, where he—dressed as a 6’4” gray mouse (shown at right)—would welcome students back to campus with his signature warmth and good humor. Bill retired in 2009, and became the first faculty member to have a classroom named in their honor. During the course of his career he earned numerous prestigious awards for teaching excellence, both locally and nationally. Bill inspired generations of students to pursue careers in teaching, urban planning, cartography, GIS, remote sensing, and other professions related to cultural geography’s focus on the Earth and how humans interact with it. About his students, he remarked “I don’t expect them all to become geographers. I just expect them to be better stewards of the Earth and its people.”

Bill spent 43 years at UWGB as a Professor of Geography and Department Chair, and postponed retirement to fill the position of Interim Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs. For decades, he hosted the Bill Laatsch Wine and Cheese Classic each fall, where he—dressed as a 6’4” gray mouse (shown at right)—would welcome students back to campus with his signature warmth and good humor. Bill retired in 2009, and became the first faculty member to have a classroom named in their honor. During the course of his career he earned numerous prestigious awards for teaching excellence, both locally and nationally. Bill inspired generations of students to pursue careers in teaching, urban planning, cartography, GIS, remote sensing, and other professions related to cultural geography’s focus on the Earth and how humans interact with it. About his students, he remarked “I don’t expect them all to become geographers. I just expect them to be better stewards of the Earth and its people.” A

A