Geography wasn’t the only major Natasha Rivers had in mind. In fact, it wasn’t even her first choice. “I originally thought I was going to study business or become a veterinarian,” she explains. It was a course on globalization that caught her attention, however, where for the first time she really learned about the core periphery of inequality and relative inequality in America. “I was interested in the people I was learning about, not just why they move and transform places that they inhabit, but the history of these people. What’s the language with the culture? What culture do they have to get rid of in order to assimilate?”

Understanding the interconnectedness of people and places has stuck with Natasha throughout her education and into her career. “It’s like, oh, okay, we’re all connected. It’s all relative,” she says. She continues on, emphasizing to this point. “But also, what can we do?”

How to create opportunity after getting a foot in the door

Natasha’s current position is the Sustainability and Measurement Director at BECU, a not-for-profit credit union, having worked her way up after originally being hired as a Program Manager. This original position initially entailed calculating the company’s carbon footprint, but that was where the environmental sustainability responsibilities ended. She quickly realized that there were so many other opportunities associated with the role, whether through expanded staff collaborations or providing members with resources. By asking questions, assessing what was needed and what was possible, while also not being afraid to make recommendations, Natasha elevated her role and presence within the organization.

How does geography play a role in your current position?

“Geography gave me a good idea of understanding people and places, of understanding the natural environment and the built environment. I’m thinking about all of these systems and how they play together with the economy. When thinking about our members, I asked for their demographics. Can we understand more about their race, education, background so that we can really deal with those different segments of the population that might need more resources or financial education?”

Using an understanding of spatial relationships to create effective initiatives in the workplace

What’s been a constant is the importance of understanding people in places. Natasha gives the example of Seattle, a place that has experienced a lot of change and growth in recent years. As a native of the city, she’s seen how the dot com and tech booms have impacted the region. “I grew up in Seattle. But Seattle’s unaffordable for most of the people in my family. So, a lot of them live in South King County.”

This diasporic movement impacts not just Natasha’s own family but the members at BECU. With her background in geography, she’s asking important questions about forced versus chosen migration and seeking answers about why and how people congregate in certain enclaves. By doing so she can better provide short- and long-term sustainability and financial health initiatives that educate members as well as staff on the connection between environmental sustainability and a financial institution.

What was your educational path? What did you study?

Natasha’s geography journey began at the University of Washington, where she double majored in Geography and American Ethnic Studies with a focus on Gender Studies. She continued on to get her PhD in Geography from University of California Los Angeles, where she built upon her interest in demography, followed by two post-docs, one at the University of Minnesota Population Center and the other at University of Washington.

“I had goals of just being an academic, publishing papers, teaching, going to conferences,” Natasha says. “That was my actual first goal. But there wasn’t a lot of opportunity at the time. This was 2010, so our country was still in the process of recovering from the Great Recession of 2008 and jobs were limited.”

If I get a Ph.D., I have to stay in academia? Right?

“So, I have this Ph.D. and it has not worked out for me and I need to figure out what my transferable skills are. I need to tap into my network and luckily my connections at the University of Washington introduced me to someone at the Seattle School District. They had just opened a new role, a Demographer role, and that was exactly my track in undergrad, grad, and my postdoc as well.”

But moving into industry from a perceived career in academia is a difficult transition. “I had to accept that and then adjust,” says Natasha. “That was the biggest adjustment: it was realizing I’m not going to have this current path, so what else is out there for me.”

How does one transition out of academia and into industry?

The key to transitioning out of academia was investing in her own professional development. Natasha had been networking for years with others in her community, from volunteering on boards to working with nonprofits, and she learned how to market herself in a non-academic way by speaking their language. Humility also played a big role in this transition. “I think a lot of times people with PhDs might go into industry and think they should be director right away or VP because of what they’ve achieved in the academic space. But I think it’s humbling to go in as a project or program manager and work your way up.”

What is your favorite part about where you work and what you do currently?

In Natasha’s current role, her favorite aspect of the job is getting to be curious and innovative. “There was no blueprint, this role was the first of its kind,” she explains. “I’m trusted to create these initiatives and do a lot of research, see what other people are doing.”

How Natasha came to work at BECU is a valuable lesson for all of us. Her previous position as a Demographer with the Seattle School District offered no opportunity for growth, and while it served her for a while, there came a time when she felt like she needed to do something more.

“A valued member of my expanded network had an opening at BECU and she had opened the role of Sustainability and Measurement,” Natasha says. “I didn’t think a financial institution would need someone thinking about the environment or sustainability. I could totally do that! So, I went for it, and I got the job.”

How does geography and its components impact not just your professional life, but your personal life?

Geography is more than a profession for Natasha, it factors into her day-to-day life as well. “There’s always the question of why was this made, or where? Where is this coming from? There are different languages being spoken here. I wonder where they came from, or what’s their journey to the U.S. It keeps me alert. It keeps me connected. It keeps me curious.”

One example came from a recent snowstorm in the Seattle area earlier this year. “Our trash wasn’t picked up for two weeks and the trash guys went on strike. So, we got these automated calls about where you can drop your trash off, but most people didn’t know where it was, even though it might be a block or two blocks from their house. Once your trash is picked up, you don’t think about it. You don’t think about where it’s going or how it’s taken care of. You just put your bin out. But when you have to take your bin TO the trash, you see all the trash there.

“I think that is what is so fascinating to me, that there are two types of people: ones that ask questions and people who don’t. Some people just want their trash picked up. But there’s others that think about the impact on the environment or how their trash is being disposed of.”

What advice do you have for geography students and early career professionals?

“Learn a lot from people, learn what you can. Don’t have such a strict view of your life, or what your career is going to look like. Be open. Keep your heart open as well. This life does surprise you, and there’s new roles that will fit exactly what you’re looking for.

“I do think that geography is relevant today, just as it was yesterday, and will be, so don’t be discouraged. There’s so much to do, so much work to be done.”

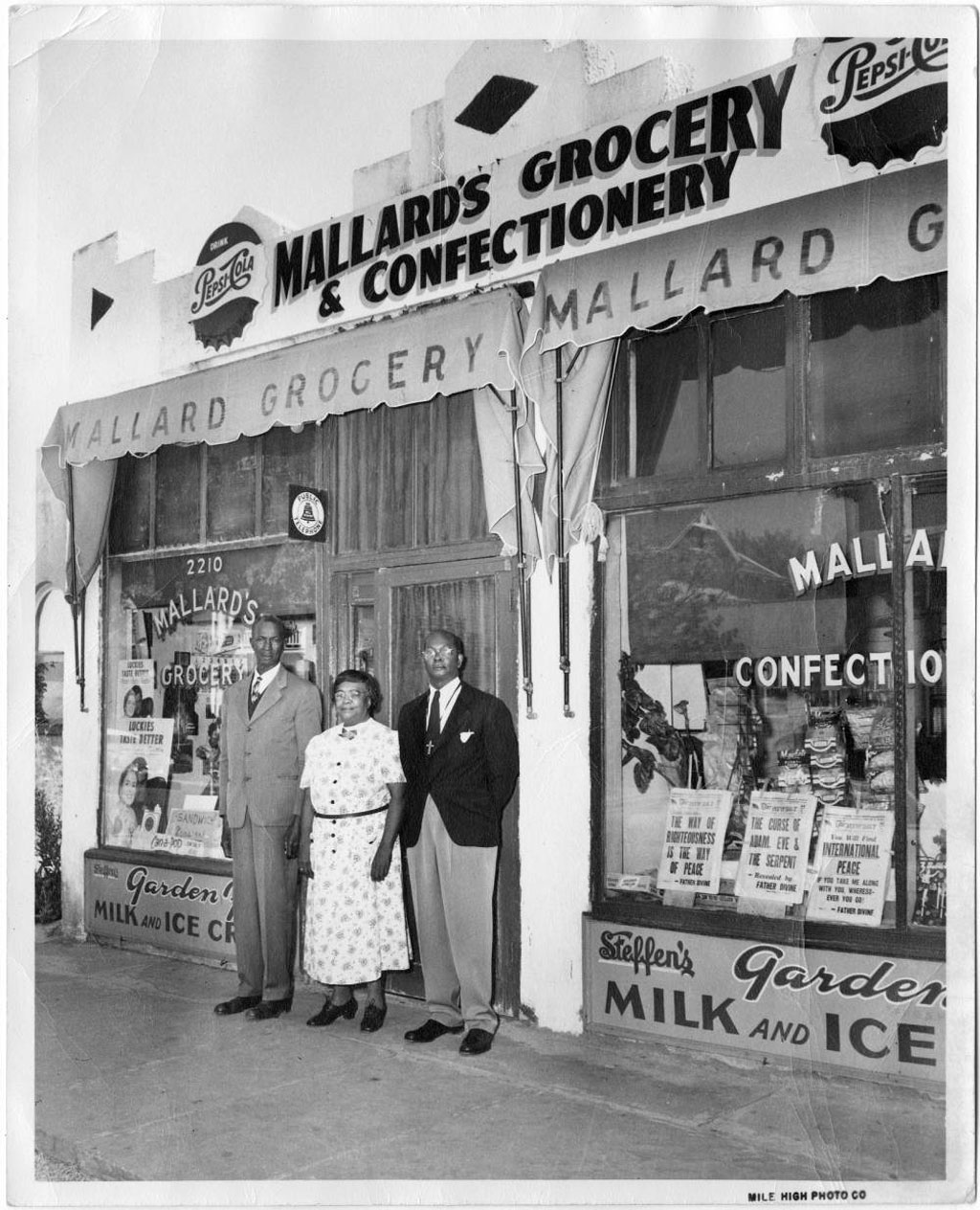

Kinkaid’s

Kinkaid’s