Regional Meeting Lollapalooza: Remarkable Spaces for Grassroots Innovation and Discussion

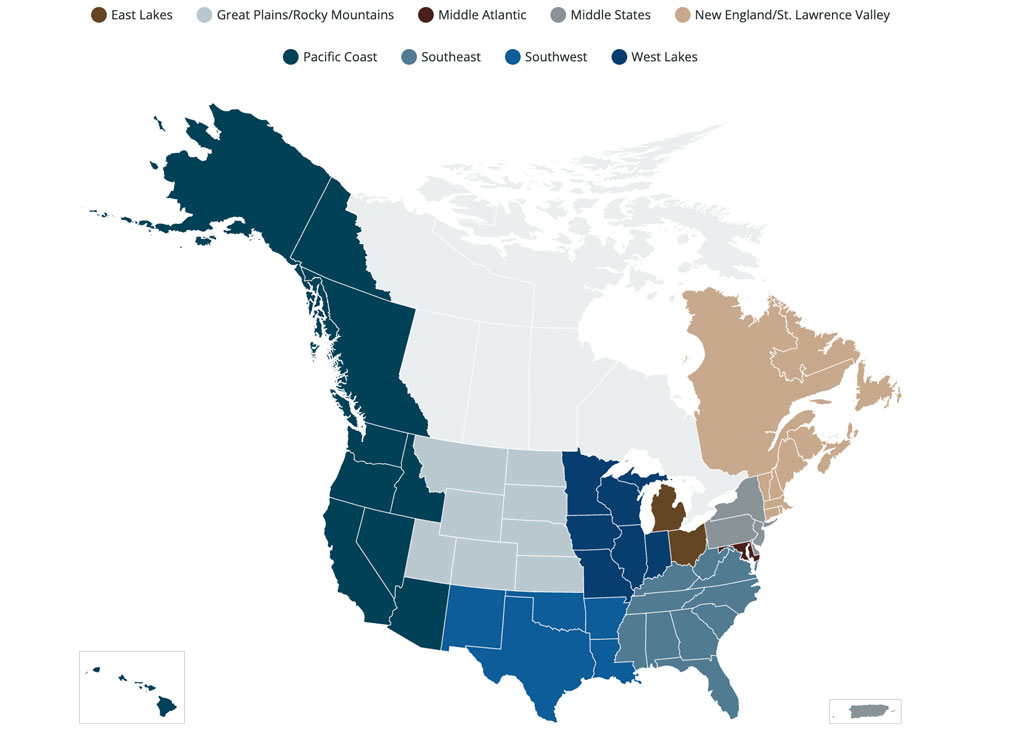

I grew up in the Chicago area, where we have an annual lakefront, summer music festival known as Lollapalooza, featuring an eclectic collection of genres and artists. This event is fun, experimental, inflected with regional traditions, and brimming with youthful, creative energy. More generically, lollapalooza refers to something extraordinary and a way I have come to think about our AAG regional meetings. This fall I had the pleasure of attending four AAG regional division meetings: Pacific Coast, Great Plains and Rocky Mountains, Southwest, and Middle States (see figure). These encounters have been tremendous opportunities for me to meet and learn from our members. Here I reflect on some broad themes across all of the meetings, as well as some key take home messages that I gleaned from each region.

Cutting across all of the regions, I was deeply impressed by the presence, energy and insights of geography students, both graduate and undergraduate. If you are ever feeling down about the headwinds facing our discipline, just spend time with our students and you will come away feeling inspired and optimistic about the future. From their scholarly endeavors shared in talks and posters, to their competitive zeal at geography bowls, to their willingness to engage in hallway conversations, I was captivated. I also have even greater appreciation for the contributions of international students to our discipline (even beyond what I have written about previously). Their presence was notable in all of the regional meetings and they help ensure that a broad range of life experiences are brought to bear on the emerging research produced by our discipline.

I also continue to be struck by the limited presence of R1 faculty at many regional meetings. Of course, there are notable exceptions to this broader trend and I also understand that this is a not a new phenomenon. I further understand some of the reasons for this (and I am also guilty of such transgressions). Many faculty are stretched in terms of time and/or resources to attend a second or third academic conference. As such, they prioritize a national meeting where the largest number of people in their subfield are sharing their latest research findings. What is lost is stronger bonds between different types of institutions in a region as well as an opportunity for undergraduate and master’s level students to potentially meet a future advisor.

Beyond these broader themes, I was really struck by the individual character of each region and some unique lessons I learned in each place. The meeting of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers (APCG) took place at the College of the Canyons in Santa Clarita, CA. There our outdoor barbecue on the second evening was graced by the presence of a dancing dinosaur (see Figure 2) and later that night a person in a gorilla costume briefly entered the auditorium for the keynote lecture (attesting to the fun and quirky ambiance of APCG meetings). More seriously, I was really struck by role that community colleges play in this region as a critical pipeline for future geographers (and something the discipline could build on more broadly). Some of the fastest growing geography programs in the region, such as San Diego State University, source many of their majors from surrounding community colleges. The APCG meeting also took place on a community college campus, College of the Canyons.

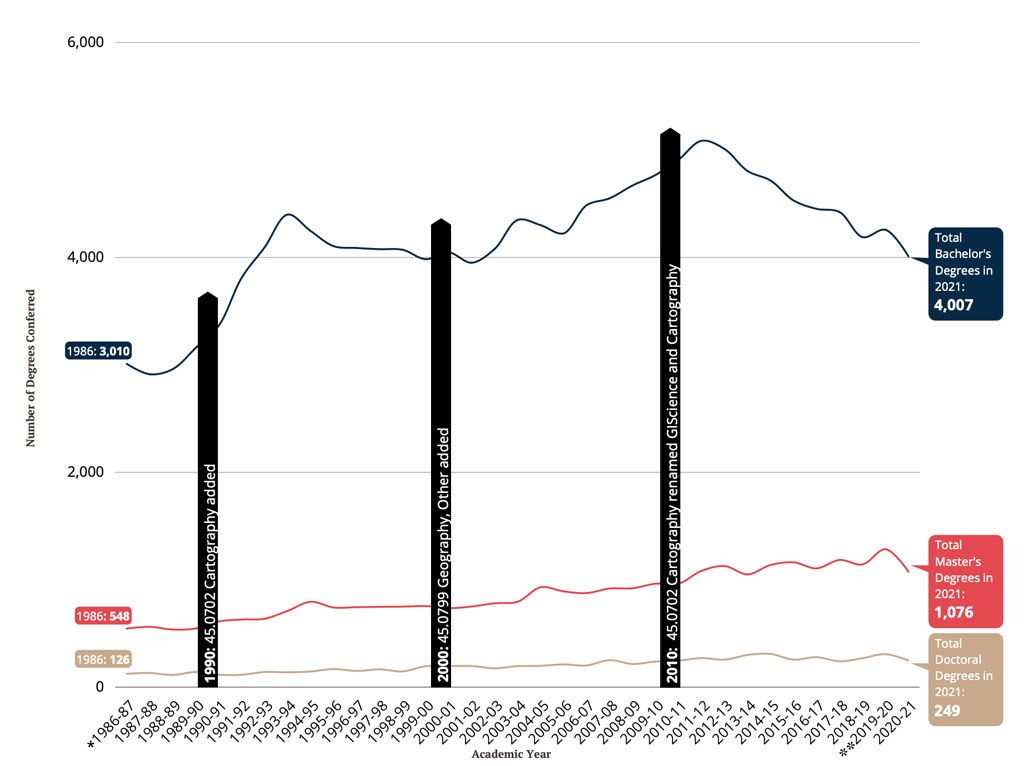

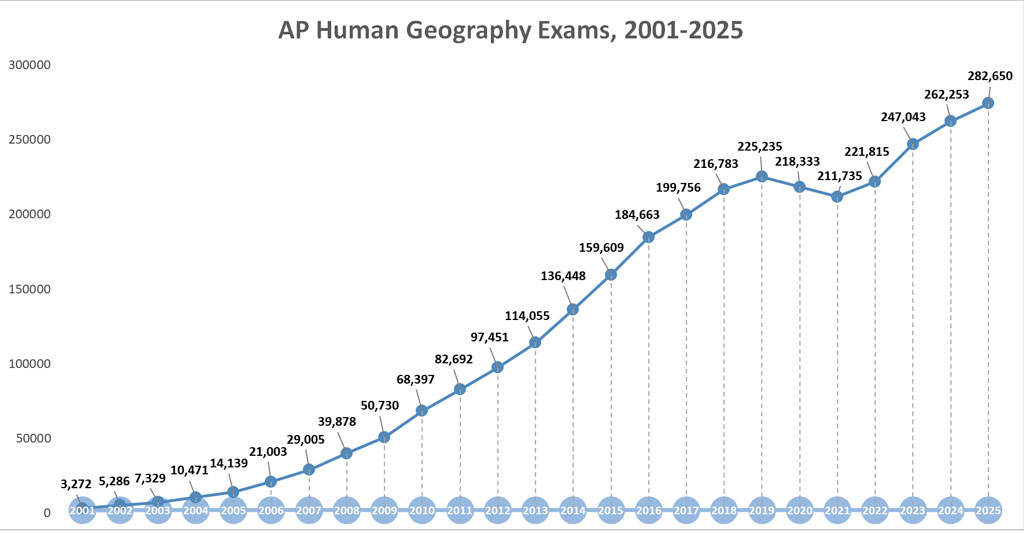

This year’s Great Plains Rocky Mountain (GPRM) regional meeting in Omaha, NE was a joint meeting with the National Council for Geographic Educations (NCGE), our sister organization that counts many high school geography teachers among its ranks. This innovative experiment of two meetings in the same place with some cross over events created a space for bridges to be built between the parallel universes of high school and college geographers. It allowed myself and two members of the AAG taskforce on geography undergraduate education to run a workshop on the high school-to-college geography pipeline for secondary school teachers and university instructors, to speak to a mixed audience at an evening banquet, and to have dinner with the leadership of the NCGE. I could see the NCGE meeting joining with other regions in the future and I believe we could do even more to bring college faculty and high school teachers together.

The meeting of the Southwest Division of the AAG (SWAAG) took place in Las Cruces, New Mexico and was hosted by New Mexico State University. In addition to a keynote address, I participated in several panel discussions, including one on academic freedom. There I learned of state government initiatives in Texas and Oklahoma to audit course syllabi and reading lists. I further came to understand that certain words and topics are being advised against in course titles, such as decolonizing, liberation and resistance. This situation is alarming to me both personally and professionally (e.g., I have publications using several of these ‘trigger’ words). More significantly, maintaining academic freedom is a core value of the AAG and something it fights for on the national level. Nonetheless, at this regional meeting, I was deeply impressed by the way faculty were sharing experiences and advice on how to navigate such challenging circumstances. It also served as a reminder that our local experiences of speech suppression, censorship or freedom can vary greatly (and we need to be sensitive to the fact that the actions and decisions of the AAG might play out differently across regional contexts).

Lastly, the Middle States Division of the AAG (MSAAG) met at Montclair State University in Montclair, NJ. There I was impressed by the presence of deeply engaged high school teachers and their students, many of whom presented research posters. The quality of their research was striking and I believe this is an innovation that could be experimented with in other regions. What could be a better recruitment tool than to have high school students attend research presentations by grad students, or to have a professor engage with a high schooler about their project and encourage them to think about a geography degree in college.

My journey across these events left me feeling inspired by the energy and insights of our students, encouraged by the experimentation in each division, and better in-touch with political currents and challenges. This is not to say the fall AAG regional meetings are flawless, some suffer from low attendance or limited organization, but I see these as vital encounters to be improved up, not dismissed or marginalized. Fortunately, the support of AAG staff for the regions has begun to bear fruit, building on the recommendations of an AAG task force report released on the topic some five years ago. Just like a summer music festival, these are fun spaces to experience the diversity, energy and creativity of our discipline.

Please note: The ideas expressed in the AAG President’s column are not necessarily the views of the AAG as a whole. This column is traditionally a space in which the president may talk about their views or focus during their tenure as president of AAG, or spotlight their areas of professional work. Please feel free to email the president directly at [email protected] to enable a constructive discussion.