Revolutionary Geographical Lessons from Mississippi Freedom Schools

By Derek H. Alderman, University of Tennessee and Joshua Inwood, Pennsylvania State University

The 60th anniversary of Freedom Summer is upon us. In the summer of 1964, several civil rights organizations, with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) often leading the way, carried out a bold campaign uniting volunteers from across the country with oppressed, often forgotten, communities in Mississippi. This effort not only combated racial discrimination but also led to widespread changes, including expanding American democracy. The campaign’s grassroots, participatory approach empowered Black people through voter registration, community organizing, and education.

The 60th anniversary of Freedom Summer is upon us. In the summer of 1964, several civil rights organizations, with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) often leading the way, carried out a bold campaign uniting volunteers from across the country with oppressed, often forgotten, communities in Mississippi. This effort not only combated racial discrimination but also led to widespread changes, including expanding American democracy. The campaign’s grassroots, participatory approach empowered Black people through voter registration, community organizing, and education.

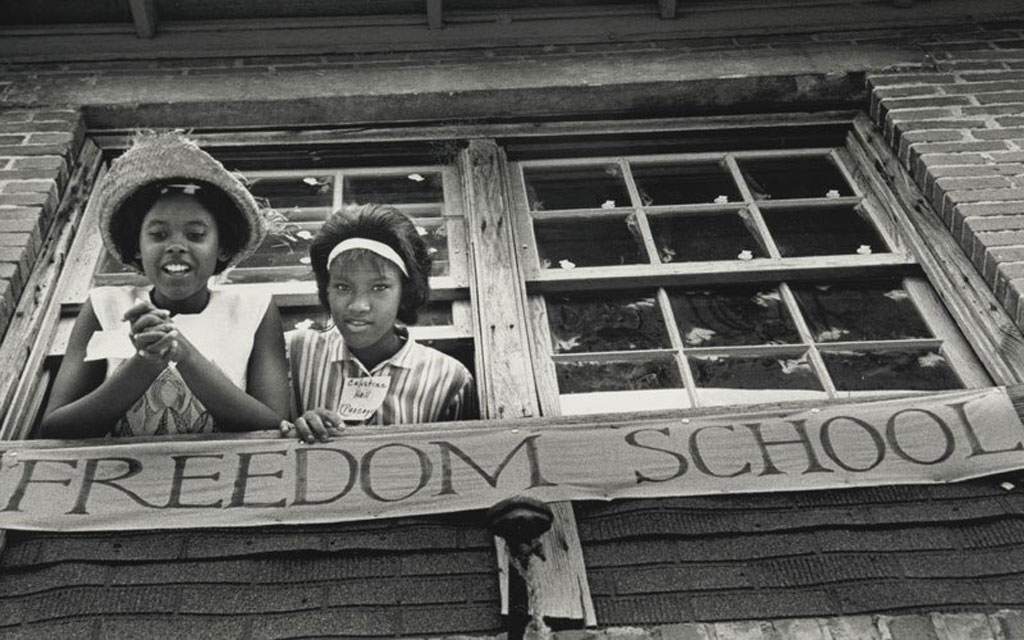

Freedom Schools were a transformative innovation of the Mississippi Freedom Project. SNCC workers and their local allies transformed churches, backyards, community centers, and other meeting places in Black communities into 41 Freedom Schools that served over 2,500 students of color. These schools provided a powerful alternative to a segregated and poorly funded state-run school system that sought to reproduce passive and demoralized Black communities—what SNCC organizer Bob Moses called the “sharecropper education.” Freedom Schools have their origin in the history of Black citizenship schools and a tradition of educational self-determination and “fugitive pedagogy” in the face of severe oppression dating back to the days of enslavement.

Freedom Schools met the basic educational needs of Black youth long denied an adequate education under racial apartheid. These schools also fostered African American creative expression, critical thinking, and appreciation for Black history and literature. These insurgent classrooms were spaces of open dialogue, encouraging students to question and challenge the ideologies and effects of racism, white supremacy, and inequalities in U.S. society. They built the self-esteem and activist skills necessary for students to participate in their own liberation. Historian Jon Hale notes that many Freedom School students worked to integrate public spaces and businesses, organize demonstrations and boycotts, and canvass communities to encourage voter registration. Although these schools operated for just six weeks in the summer of 1964, they proved influential in creating a revolutionary cadre of young Black Mississippians ready to take on the role of citizen leaders in their communities. Freedom Schools have continued to inspire educational models of social justice that are still found today.

Although scholars have often overlooked this fact, Geography was a pivotal part of the Freedom School curriculum. Freedom Schools offered revolutionary spatial learning and inquiry, focusing on Black students and their families’ often-ignored struggles and needs. Though not explicitly stated, the curriculum developers sought to spur students to develop an ‘anti-racist regional knowledge.’ This regional knowledge was not just a collection of facts and figures but a tool for understanding and challenging the power relations undergirding the building of the Deep South as a racially unjust region. It was an embodied and visceral form of geographic learning in which SNCC empowered students to reflect on their personal experiences with Jim Crow discrimination and identify the social and geographic forces behind their oppression. Running through the Freedom School curriculum was an idea made popular many years later by Clyde Woods, who argued that racialized underdevelopment in the South did not simply happen. It resulted from a monopoly of white power, what Woods called the “plantation bloc,” arresting the development opportunities of Black people – even as these oppressed communities found ways to survive and create.

Clyde Woods…argued that racialized underdevelopment in the South did not simply happen.

In our National Science Foundation-funded research, we have examined the Freedom School curriculum closely regarding geographic education, finding that these pedagogical ideas went beyond how Geography was taught in many schools and universities at the time. While top academic geographers in 1964 debated how to make the field more scientifically precise and the merits of systematic versus regional approaches, SNCC was in Mississippi creating course content that directly connected U.S. racism and segregation to broader regional and national analysis and putting its organic geographic intellectualism in the service of racial equality. The disconnect between Geography in Freedom Schools and what was practiced by ‘professional geographers’ speaks not just to the path-breaking nature of Freedom Summer but also to the complicity of our disciplinary spaces and practices in historically ignoring and excluding Black communities.

Along with colleagues Bethany Craig and Shaundra Cunningham, our paper in the Journal of Geography in Higher Education delves into Freedom Schools as a neglected chapter in geographic education. We highlight the curricular innovations they deployed in producing geographic knowledge accountable to Black experiences, communities, and places. Freedom School curriculum called on students to critically use geographic case studies to conduct regional comparisons — both within the U.S. and internationally — to situate Mississippi and the South within broader racial struggles and human rights geographies to raise the political consciousness and expand students’ relational sense of place.

At Freedom Schools, students developed skills using data from the U.S. Census and other sources to understand racial disparities in income and housing across communities in Mississippi and concerning their own families. Freedom Schools engaged students in interrogating the material landscapes of inequality to ask probing questions about the unjust distribution of resources from place to place. The curriculum frequently used maps, not just as passive locational references. Black students were given opportunities to produce “power maps,” which charted the social and spatial connections and networks between institutions and influential people undergirding the oppressive conditions in their community. Plotted on these unconventional but important cartographies were the larger geographic scales of power driving white supremacy—from the local to the national.

The disconnect between Geography in Freedom Schools and what was practiced by ‘professional geographers’ speaks not just to the path-breaking nature of Freedom Summer but also to the complicity of our disciplinary spaces and practices in historically ignoring and excluding Black communities.

As the nation remembers Freedom Summer, we encourage colleagues to delve into the revolutionary Geography lessons at work in Freedom Schools. This curriculum offers a window into the Black Geography knowledge production that always undergirded the Civil Rights Movement. It is an essential counterpoint to popular treatments that give too little attention to the intellectual labor and sophisticated planning behind the Movement. Black geographies of education, such as those found in Freedom Schools, provide an important avenue for recovering too easily forgotten activists and activism and how educational reform remains unfinished civil rights work.

Yet, examining the Freedom School curriculum is of more than historical importance. It directly inspires a question of importance to contemporary geography educators: How can we design a curriculum that serves not just the intellectual debates and interests of the field but responds directly to the everyday experiences, needs, and well-being of students and others from historically marginalized groups? When we publish critical research on equity and social justice, do we actively consider how that scholarship could translate to and impact educational praxis? As our field struggles with addressing issues of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) and broadening participation as well as the relevance of Geography in an environment of education retrenchment, it is essential to note that students of color yearn for an educational experience that responds to their humanity and daily struggles.

Toward a Geography of Freedom

Freedom Schools provoke us to ask: Are we doing enough to articulate a vision of geographic education that addresses and intervenes in the struggle for freedom? Do we project within our classrooms a geographic perspective that helps historically excluded student groups make sense of and challenge their oppression and recognize their historical and contemporary contributions to building the nation and the wider world? As a discipline, are we doing what Freedom Schools did in helping our students develop the skills to identify and resist structural inequalities?

More and more geographers are committed individually and departmentally to these questions. Still, Freedom Schools provokes us to consider whether a more systemic approach is needed to rebuild Geography education and curriculum. Freedom Schools provide a moment for our field to re-evaluate and broaden what counts as geographic learning, whose lives matter in our curriculum, and what social and political work geographic pedagogy should accomplish. Several years ago, a group of educational specialists developed a set of widely distributed National Geography Standards called Geography for Life, which stops short of prominently promoting peace, social and environmental justice, and anti-discrimination. Don’t we need a new set of curricular standards borrowed from 1964 Mississippi, called Geography for Freedom?

Black geographies of education, such as those found in Freedom Schools, provide an important avenue for recovering too easily forgotten activists and activism and how educational reform remains unfinished civil rights work.

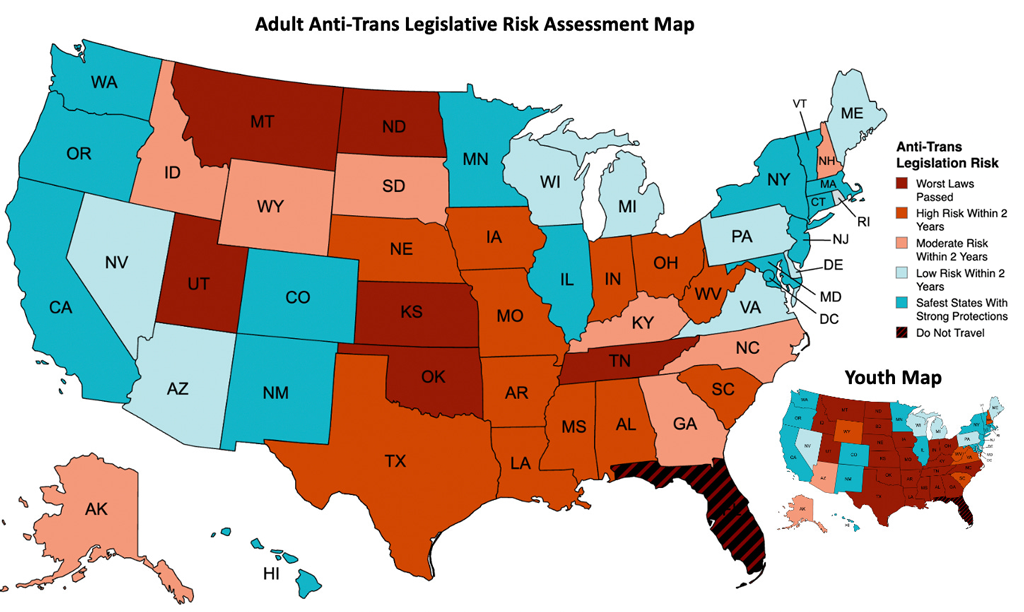

Crafting a Geography for Freedom curriculum should be a shared responsibility and involves collaborating with K-12 educators. Our K-12 colleagues have been hit especially hard by growing pressure from states, school districts, and parents to limit the very kind of discussions about racial injustice once held sixty years ago in Freedom Schools. Many university professors wrongly assume that their jobs and programs in higher education are somehow separate from and not impacted by Geography at the primary and secondary levels. The chilling, if not the absolute loss, of the right to tell and teach truths in classrooms can spread to higher education, and there are signs that it already has done so.

Reforming and rewriting the geographic curriculum taught at educational institutions is crucial. Yet, the Freedom Schools’ legacy of operating independently of and in opposition to the state should provoke us to expand the spatial politics of where teaching and learning happen. It is necessary to move beyond the traditional classroom to develop a Geography for Freedom curriculum within what Jacob Nicholson calls “alternative, non-formal educational spaces” — whether that be teach-ins, reading and writing groups, afterschool and summer programs, teacher advocacy workshops, people’s schools or assemblies, mobile geospatial/citizen science labs, community radio shows, film screenings, or producing zines, infographics, and pamphlets.

Looking back upon Mississippi’s Freedom Schools and ‘discovering’ the role that Geography played in its educational activism should not be a feel-good moment for us in academic or professional geographic circles. Instead, it should push us to engage in a sober reckoning about what more our field can and should do to embrace the ideals and spatial imagination of Freedom Summer. We are 60 years behind, and it is time to catch up.

Perspectives is a column intended to give AAG members an opportunity to share ideas relevant to the practice of geography. If you have an idea for a Perspective, see our guidelines for more information.

Often underemphasized in higher education is the important role played by community colleges, which continue to be responsible for the education of 38% of all American undergraduates enrolled in public colleges and universities. Although

Often underemphasized in higher education is the important role played by community colleges, which continue to be responsible for the education of 38% of all American undergraduates enrolled in public colleges and universities. Although

This column is the second in a series from the AAG Healthy Departments Committee that is focused on ways to ensure higher education futures include robust, healthy geography programs. In this column, Risa Palm and Jon Harbor, two geographers who have served as deans and provosts across several types of institutions of higher education, provide their perspectives on positioning an academic unit for success. In the previous column, David Kaplan set the scene with “

This column is the second in a series from the AAG Healthy Departments Committee that is focused on ways to ensure higher education futures include robust, healthy geography programs. In this column, Risa Palm and Jon Harbor, two geographers who have served as deans and provosts across several types of institutions of higher education, provide their perspectives on positioning an academic unit for success. In the previous column, David Kaplan set the scene with “

Over the next several months, we’ll devote space in this column to the perspectives of JEDI Committee chairs as they continue implementing AAG’s Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) plan through the framework of

Over the next several months, we’ll devote space in this column to the perspectives of JEDI Committee chairs as they continue implementing AAG’s Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) plan through the framework of  The weeks and months following the 2020 murder of George Floyd by police officers in Minneapolis saw an outpouring of public support for racial justice in the United States. America, it seemed, was ready for a long overdue ‘racial reckoning’. American corporations, government agencies, and academic institutions hurried to introduce an array of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) measures designed to address institutional barriers to equality.

The weeks and months following the 2020 murder of George Floyd by police officers in Minneapolis saw an outpouring of public support for racial justice in the United States. America, it seemed, was ready for a long overdue ‘racial reckoning’. American corporations, government agencies, and academic institutions hurried to introduce an array of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) measures designed to address institutional barriers to equality. In many respects this should be a time of rising attention and support for geography. The concerns of the planet — global climate change, geopolitical turmoil, social and spatial justice — are those that speak to geography’s strengths. Geography scholars have been recognized with Guggenheims, MacArthurs, National Academy invitations and other honors. Geospatial technologies are standard throughout business and government, and geographers are best poised to educate geospatial practitioners and develop new technologies. We are also a STEM discipline, which puts us at a strategic advantage given the priorities of many universities these days.

In many respects this should be a time of rising attention and support for geography. The concerns of the planet — global climate change, geopolitical turmoil, social and spatial justice — are those that speak to geography’s strengths. Geography scholars have been recognized with Guggenheims, MacArthurs, National Academy invitations and other honors. Geospatial technologies are standard throughout business and government, and geographers are best poised to educate geospatial practitioners and develop new technologies. We are also a STEM discipline, which puts us at a strategic advantage given the priorities of many universities these days.