Harlem of the West: Jazz, People, and Place in the Fillmore

By Mirembe Ddumba

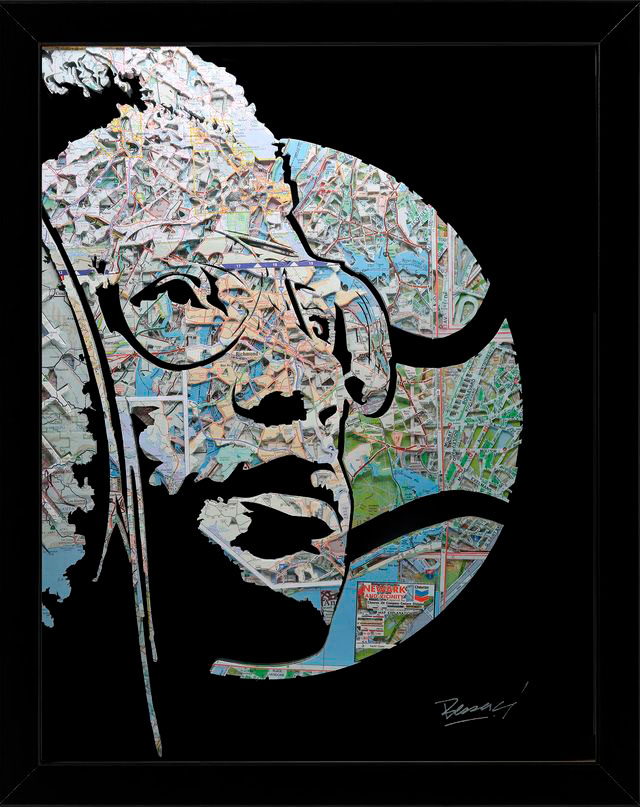

Stand on Fillmore and Geary streets on a Saturday evening, and you can almost hear it. Neon humming against the dusk, a saxophone warming up behind a church door, the ghost of Billie Holiday’s voice floating between the streetlights. In these few streets, jazz wrote itself onto San Francisco’s grid.

The sound arrived by train.

The Sound of Migration

During World War II, African Americans from Louisiana, Texas, and across the South boarded trains bound for San Francisco’s shipyards. Between 1940 and 1950, the city’s Black population grew tenfold, from 4,800 to 43,000, filling apartments left empty when Japanese American families were forced into internment camps.

Musicians arrived with guitars slung over shoulders, horns wrapped in cloth. They transformed twenty blocks into the “Harlem of the West.” By the late 1940s, you could walk Fillmore Street on any night and hear Dizzy Gillespie bleeding through one door, smell barbecue from the next, watch Cadillacs pull up to drop off couples dressed for Jimbo’s Bop City.

Bop City at 1690 Post Street ran after-hours sessions until sunrise. Charlie Parker traded choruses with Dexter Gordon while Billie Holiday sat in a corner booth. Down the street, Ella Fitzgerald sang at the Champagne Supper Club and tried on hats between sets. The Blue Mirror. Club Flamingo. Jack’s Tavern. Two dozen venues within one square mile, each separated by a five-minute walk.

John Coltrane, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Louis Armstrong, and Thelonious Monk rented rooms above the clubs, ate at soul food diners, bought records at local shops, and shaped the neighborhood’s sonic identity night after night. This wasn’t accidental. The grid itself made it possible.

Geography as Destiny

The Fillmore’s layout made this density possible. Narrow Victorian storefronts, twenty feet wide, meant multiple clubs per block. Short blocks with corner entries created constant foot traffic. The 22-Fillmore streetcar brought audiences from downtown, turning the neighborhood into one continuous jazz experience.

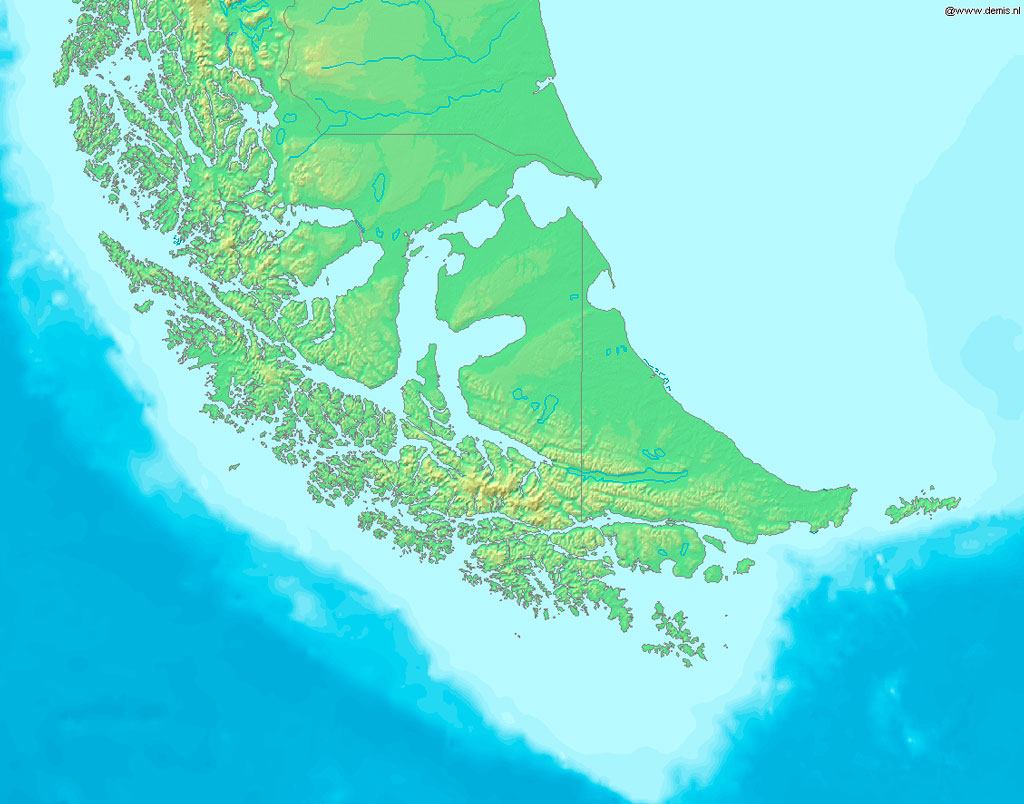

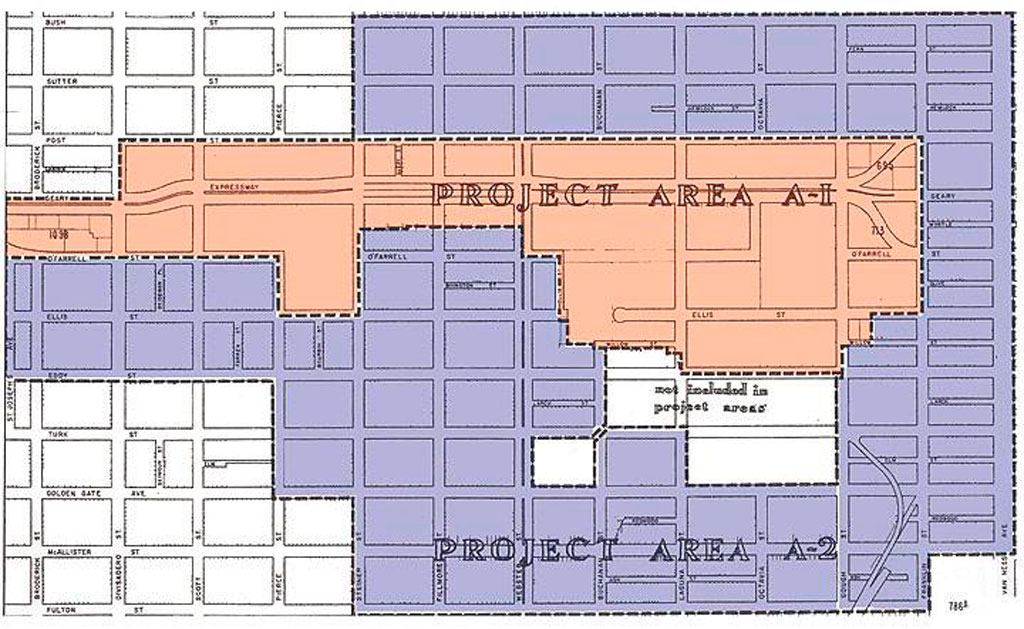

In 1948, city planners declared the Fillmore “blighted.” Under Redevelopment Agency director M. Justin Herman, bulldozers arrived. The Western Addition A-1 and A-2 projects demolished Victorian homes and shuttered clubs across 104 blocks. Geary Street, once lined with music venues, became Geary Boulevard, a four-lane expressway cutting the neighborhood in half.

By 1964, authorities had displaced 4,000 residents from A-1 alone. Jazz musicians scattered to Oakland, the East Bay, and Los Angeles. Residents gave urban renewal a different name: “Negro Removal”.

You could go out on Friday night and not come home until Sunday night because there is so much to do.”

—Elizabeth Pepin Silva, filmmaker and author of Harlem of the West

The clubs closed. The musicians left. But the music never completely died.

Still Playing

Walk Fillmore Street now, and commemorative plaques mark where Bop City stood, where the barbershop was, where musicians bought their reeds. Listen closely, though. The Fillmore Auditorium still books acts, its walls papered with decades of concert posters. Calvary Presbyterian Church hosts Sunday jazz services. Jones Memorial United Methodist Church opens its doors for Friday night sessions.

Every July since 1986, the Fillmore Jazz Festival closes twelve blocks to cars. Over 50,000 people flooded the streets for two days. Five stages. Artisan booths. The smell of Ethiopian food mixing with New Orleans-style barbecue. For one weekend, the neighborhood becomes what it was, pedestrians moving from stage to stage, music echoing off Victorian facades.

On other nights, the music lives in smaller rooms. 1300 on Fillmore books jazz acts in an intimate room with velvet couches. The Boom Boom Room sits on the corner where John Lee Hooker used to own a club. Rasselas Ethiopian Restaurant serves injera and hosts live music Thursday through Sunday. The building that housed Jimbo’s Bop City was literally picked up and moved two blocks west. It’s Marcus Books now, an Afrocentric bookstore that archives what redevelopment tried to erase.

Stand at Fillmore and Geary on Saturday evening. Close your eyes. Past the bus engines and car horns, you can still hear it. A saxophone warming up. The ghost of a neighborhood that jazz built, that policy tried to destroy, and that memory refuses to let die.

Learn More

- Harlem of the West: The San Francisco Fillmore Jazz Era by Elizabeth Pepin Silva and Lewis Watts

- Interactive Map: Historic Fillmore Jazz Venues (FoundSF)

- San Francisco African American Historical & Cultural Society

- KQED’s Fillmore History Timeline

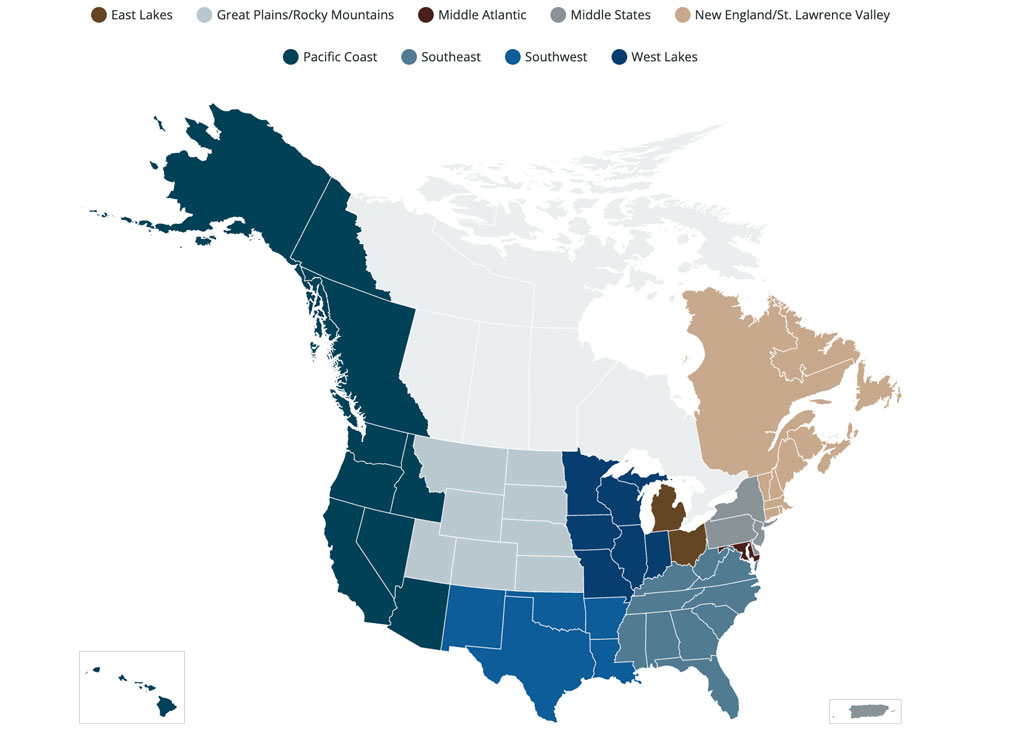

Jennifer Clapp is this year’s AAG Honorary Geographer. She is recognized for her groundbreaking work at the intersection of global economy, food systems, and food security, along with her commitment to praxis, including her current service as a member of the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food), and her previous service on the Steering Committee of the High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE-FSN) of the United Nations Committee on World Food Security (CFS) from 2019-2023 (vice chair 2021-2023).

Jennifer Clapp is this year’s AAG Honorary Geographer. She is recognized for her groundbreaking work at the intersection of global economy, food systems, and food security, along with her commitment to praxis, including her current service as a member of the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food), and her previous service on the Steering Committee of the High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE-FSN) of the United Nations Committee on World Food Security (CFS) from 2019-2023 (vice chair 2021-2023). Anthony Howell is the new Geographic Methods editor for the Annals of the American Association of Geographers. He is an associate professor, director of the Center on Technology, Data, and Society (CTDS), and senior sustainability scientist at Arizona State University. Howell brings to the editorship at Annals a background in computational, geospatial and quantitative social science methods. He currently serves as an associate editor for two journals (Progress in Economic Geography and Urban Governance) as well as having served as a guest co-editor for Economic Modeling. He works across several subspecialties in geography, including economic geography, industrial geography, development geography, and population geography, as well as the broader social sciences.

Anthony Howell is the new Geographic Methods editor for the Annals of the American Association of Geographers. He is an associate professor, director of the Center on Technology, Data, and Society (CTDS), and senior sustainability scientist at Arizona State University. Howell brings to the editorship at Annals a background in computational, geospatial and quantitative social science methods. He currently serves as an associate editor for two journals (Progress in Economic Geography and Urban Governance) as well as having served as a guest co-editor for Economic Modeling. He works across several subspecialties in geography, including economic geography, industrial geography, development geography, and population geography, as well as the broader social sciences. We thank longtime, outgoing editor Dr. Ling Bian, an AAG Fellow and professor in the Department of Geography at the University at Buffalo. Dr. Bian has been the Geographic Methods editor of the Annals since 2018, and also serves or has served on the editorial boards of numerous geography and GIScience journals, as well as on review panels for the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. Her current research interests include conceptual and analytical frameworks for the representation of dynamic geographic phenomena, individual-based and spatially explicit modeling of health behaviors, and spatial networks. During her tenure as an Annals editor, Dr. Bian has dedicated her efforts to advancing the geography discipline by promoting intellectually in-depth and socially relevant research outcomes.

We thank longtime, outgoing editor Dr. Ling Bian, an AAG Fellow and professor in the Department of Geography at the University at Buffalo. Dr. Bian has been the Geographic Methods editor of the Annals since 2018, and also serves or has served on the editorial boards of numerous geography and GIScience journals, as well as on review panels for the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. Her current research interests include conceptual and analytical frameworks for the representation of dynamic geographic phenomena, individual-based and spatially explicit modeling of health behaviors, and spatial networks. During her tenure as an Annals editor, Dr. Bian has dedicated her efforts to advancing the geography discipline by promoting intellectually in-depth and socially relevant research outcomes.

This is the sixth of a short series of perspectives by 2024-2026 Council Treasurer Antoinette WinklerPrins — a series designed to help illuminate some of the financial challenges a professional organization such as the AAG faces. In this column, she offers perspectives on the financial aspects of running the AAG Annual Meeting.

This is the sixth of a short series of perspectives by 2024-2026 Council Treasurer Antoinette WinklerPrins — a series designed to help illuminate some of the financial challenges a professional organization such as the AAG faces. In this column, she offers perspectives on the financial aspects of running the AAG Annual Meeting.

Geography in the News is an educational series offered by the American Association of Geographers for teachers and students in all subjects. We include vocabulary, discussion, and assignment ideas at the end of each article.

Geography in the News is an educational series offered by the American Association of Geographers for teachers and students in all subjects. We include vocabulary, discussion, and assignment ideas at the end of each article.