Member Profile: Kenneth Martis

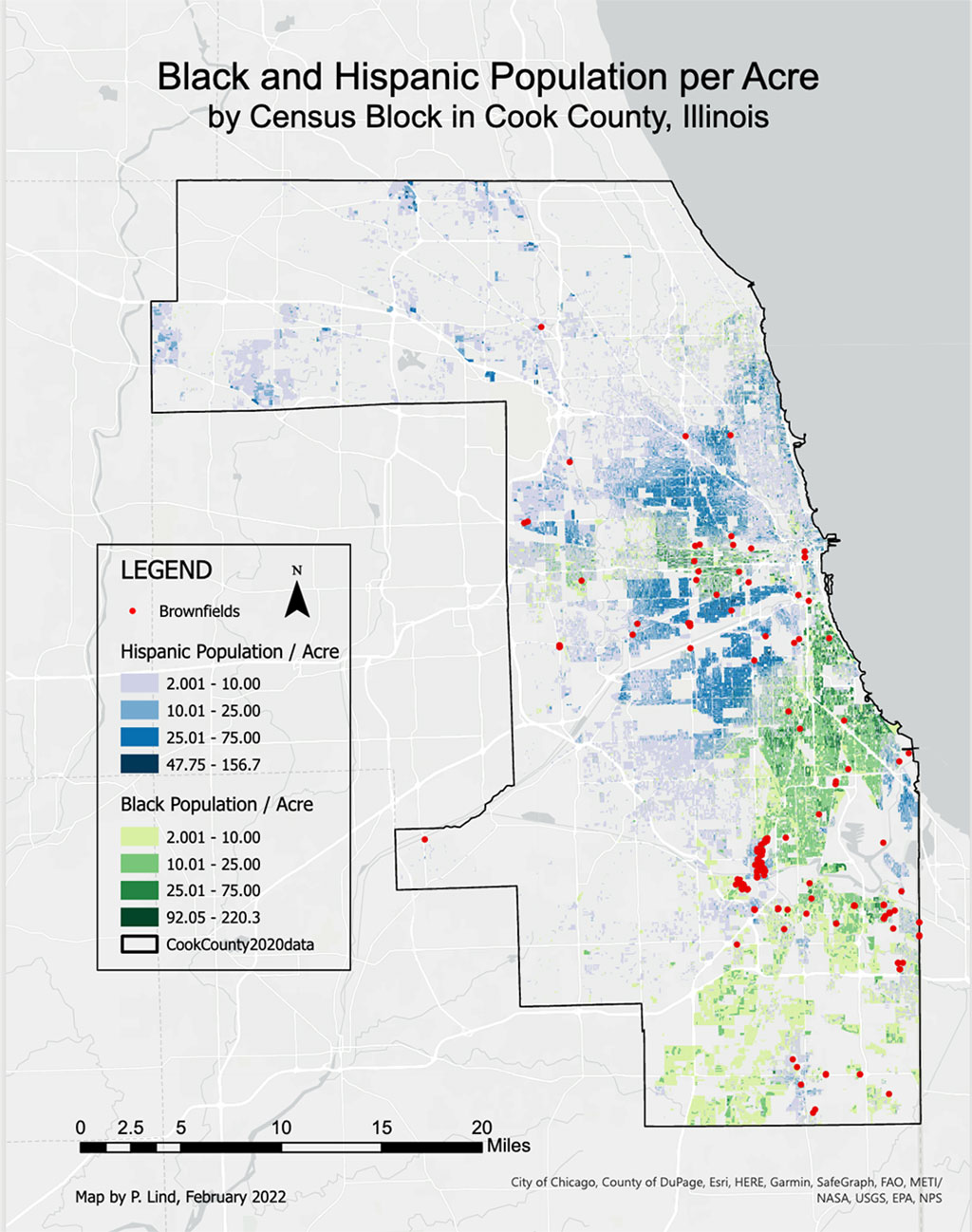

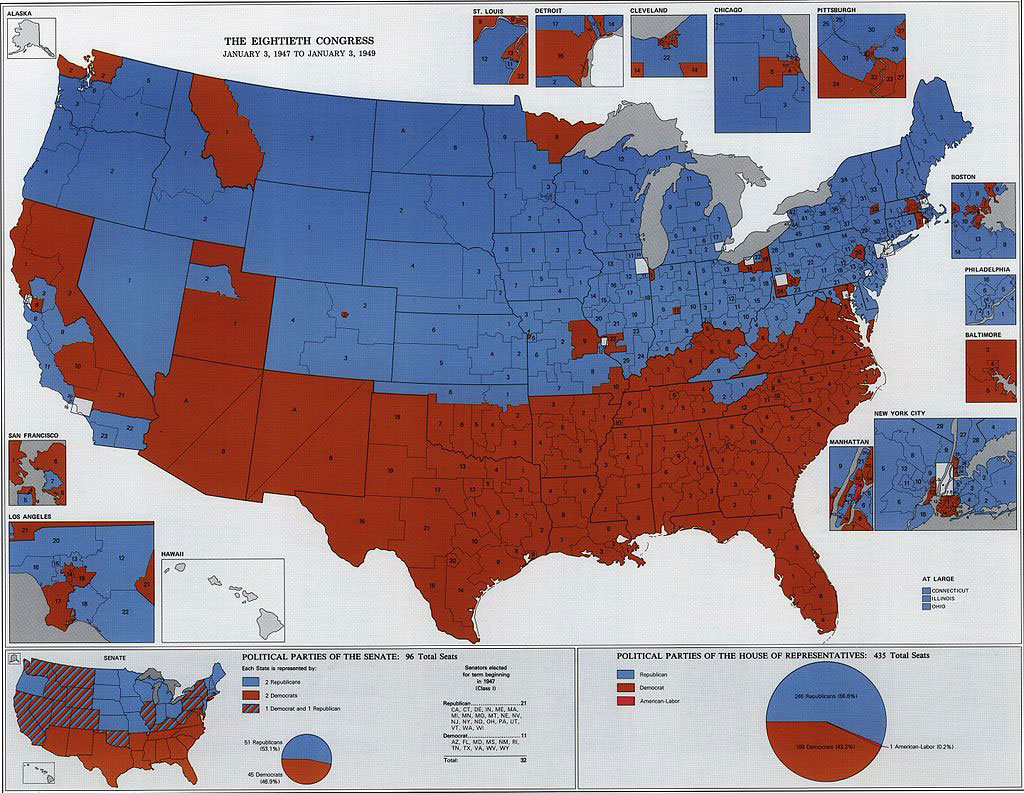

As a graduate student at the University of Michigan in 1972, Ken Martis stumbled on one of the greatest information vacuums in political geography — the lack of documentation for congressional districts since the founding of the United States. He decided then and there to fill the gap. His quest would result in groundbreaking research, nine books, and a lifelong calling.

“I had just chosen a dissertation topic,” Martis recalls, “which was mapping roll call votes in the United States Congress. I was focused on voting patterns on natural resources, conservation, and the environment through time, starting with the earliest congresses through the environmental issues of the 1960s.” To get started, Martis went to the university library — one of the biggest in the nation at the time — to find national-scale district maps for the last 170 years. The reference librarian took him through the card catalog. Then the Guide to Reference Books. They could find nothing. “She was as puzzled as me. She told me to give the staff a chance to look into it, and to return the next day. So I did. I was met by the librarian and the head of the reference department. They’d turned up nothing, not even for landmark eras like Abraham Lincoln’s time.”

“I realized I could be the first person in American history to map every congressional district from the First Congress forward,” he says. “It was humbling, and exciting.”

Martis is now Professor Emeritus in the Geology and Geography Department at West Virginia University. He is the author or co-author of award-winning books that have fundamentally shaped our awareness of political patterns in the United States. His first historical political atlas was The Historical Atlas of United States Congressional Districts: 1789-1983, with maps by cartographer Ruth A. Rowles. This book was the first to map every congressional district and analyze every apportionment change for every state for all of United States history. It won numerous honors, including the American Historical Association’s Waldo G. Leland Prize for the best reference book in all fields of history for the period 1981-1986. He went on to write eight additional volumes with partners, including a historical atlas of congressional political parties, a historical atlas of congressional apportionment, and the 2006 Historical Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections 1788-2004. He has continued to document the American political landscape with co-edited works on the pivotal 2012, 2016, and 2020 elections.

Geography as Lifeline

Martis’s four grandparents and father were Slovakian immigrants from Austro-Hungary in the early 1900s. He was also the first in his family to finish high school, attend college, and attain advanced degrees. “My mother saved my grade school report cards,” he says. “They show I was a poor to average student, except in one area; geography! I loved it.”

His love of geography saved his academic career in college at the University of Toledo. After several semesters he describes as “disastrous” and himself as “barely surviving,” Martis took geography courses with engaging professors, and found his academic passion. One Toledo geography professor in particular, Dr. Donald Lewis, took Martis under his wing. “I have told him several times, he is my number one influence in becoming geographer.”

I realized I could be the first person in American history to map every congressional district from the First Congress forward.”

The selection of geography courses and excellent professors were no accident. “The Department of Geography at the University of Toledo is a story unto itself,” says Martis. In 1958, the university appointed a new president, arctic geologist Dr. William S. Carlson. Carlson earned his B.A., M.S., and Ph.D. from the University of Michigan, where his graduate advisor was geologist William Herbert Hobbs, president of the Association of American Geographers in 1936. In 1963 President Carlson finalized the creation of a new stand-alone Department of Geography and hired full-time tenure-track faculty. Martis was among the first beneficiaries of this investment.

“Your journey in life is marked by the many choices or paths you select,” he says now. “Nevertheless, the mere existence of the path is predicated by hundreds of choices previously, mostly by people you will never know. What if William Carlson had chosen another advisor in the 1930s? Or what if he chose to remain President of the University of Delaware in 1958? What if Professor Lewis had not taken me under his wing? I believe there is no journey to geography for me if there was no Hobbs, no Carlson, no Lewis, and no establishment of Toledo geography.”

At San Diego State University, Martis discovered political geography. Mentored by Dr. Jim Blick, he was able to complete his thesis even as he lived through the uncertainty of preparing to report to the U.S. Army in the middle of the Vietnam War. After a two-year stint in the Army, he applied to the University of Michigan, under dissertation supervisor George Kish. As his career advanced, mentors and colleagues such as Stanley Brunn, Ruth Anderson Rowles, J. Clark Archer, Gerald Webster, and Fred Shelley collaborated and supported his participation in American electoral geography beyond Congress to presidential elections, gerrymandering, specific elections, and the highlights of political eras and history.

Over his nearly 50 years as a professor at West Virginia University, Martis has seen great growth, including the addition of a Ph.D. program. A critical factor in the department’s development was the incorporation of GIS into the program during the 1980s and 1990s, led by Gregory Elmes and Trevor Harris. WVU also gave faculty the academic freedom to pursue their research interests, and proximity to research resources helped, too: Morgantown is about four hours from the National Archives and Library of Congress, where Martis spent many hours over the years.

Martis’s research continues to have lasting impacts in the public arena. Using modern GIS technology and historical digital boundary databases, UCLA has worked with Martis’s maps to create highly detailed district lines that are now the standard in congressional boundary history. Martis’s work has been used by investigative journalists and attorneys to show the history of anti-democratic gerrymandering. He has also been a consulting volunteer with the League of Woman Voters and Common Cause in their effort for fair maps, and served on the organizing committee for the AAG redistricting webinars in 2021.

“I consider myself a historical political geographer with a passion for maps,” says Martis. “I am 11 years past retirement. I am still doing geography. It looks like I always will.”

As a child, Pinki Mondal eagerly awaited her father’s arrival home from long trips around the world, working for one of India’s mercantile navy companies. Her earliest geography lessons came in special moments with him: “When he used to come back home, we would sit down with a map like an Atlas, and he would ask me, ‘give me a country name.’ And my job was to point that out on a map.”

As a child, Pinki Mondal eagerly awaited her father’s arrival home from long trips around the world, working for one of India’s mercantile navy companies. Her earliest geography lessons came in special moments with him: “When he used to come back home, we would sit down with a map like an Atlas, and he would ask me, ‘give me a country name.’ And my job was to point that out on a map.”

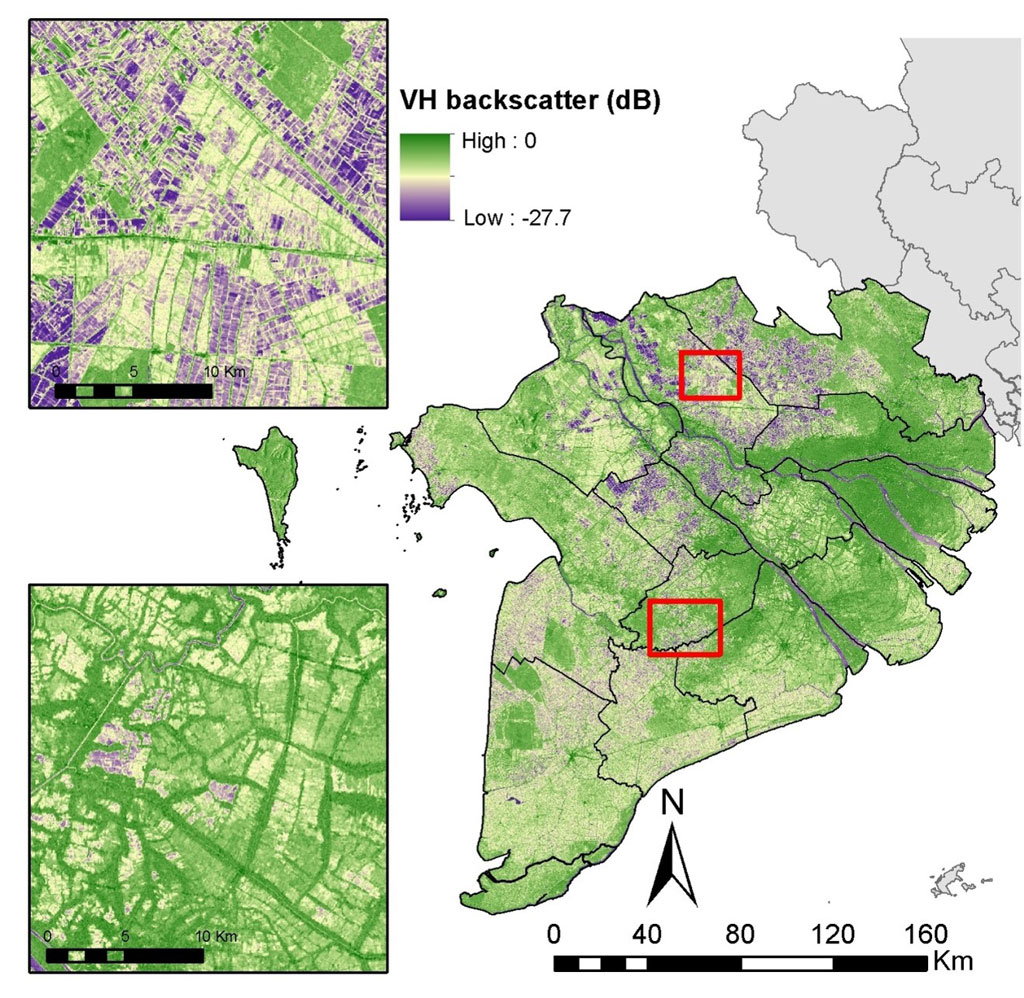

Mark Ortiz was almost finished with his bachelor’s degree at the University of Alabama, doing a self-designed major in environmental studies, when he realized that geography offered him the space to study nature and society in connection with one another. “I started reading work in critical geography and political ecology and felt that it was a natural fit where I could pursue the intersectional questions that interested me,” he says. He went on to earn his master’s and Ph.D. in geography from UNC-Chapel Hill.

Mark Ortiz was almost finished with his bachelor’s degree at the University of Alabama, doing a self-designed major in environmental studies, when he realized that geography offered him the space to study nature and society in connection with one another. “I started reading work in critical geography and political ecology and felt that it was a natural fit where I could pursue the intersectional questions that interested me,” he says. He went on to earn his master’s and Ph.D. in geography from UNC-Chapel Hill.

Kinkaid’s

Kinkaid’s