The Neighborhoods of Boston … and Beyond

Every day is a new day in Boston. Parks and green spaces are sprouting up all over, new hotels have recently opened, and more are soon to break ground. New restaurants are joining Boston’s distinctive dining scene and the vibrant Seaport District has added to the city’s already dynamic downtown neighborhoods. Below is an overview of the many diverse neighborhoods in and around Boston.

The Back Bay: The Back Bay was planned as a fashionable residential district, and was laid out as such by the architect Arthur Gilman in 1856. Having traveled to Paris, Gilman was heavily influenced by Baron Haussmann’s plan for the new layout of that city. The result of Gilman’s inspiration is reflected in the Back Bay thoroughfares that resemble Parisian boulevards.

In the mid-19th century, Boston’s Back Bay tidal flats were filled in to form the 450-acre neighborhood, which we now know as the Back Bay. Prior to this time, the Back Bay was used for little more than milling operations.

As the tidal flats were slowly filled in, beginning at the edge of the Public Garden and extending westward, residential construction followed. Because the land filling efforts proceeded slowly, construction advanced concurrently on filled-in lots as they became available. As a result, most blocks in the Back Bay date from approximately the same era and, when viewed in sequence, illustrate the changing tastes in and stylistic evolution of American architecture over the course of the mid- to late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Commercial buildings were erected alongside these residential structures, primarily on Newbury and Boylston Streets. Commercial development began on Boylston Street around 1880 and on Newbury Street in the early 20th century. While new structures were built for some of these commercial ventures, others adapted existing row houses for their purposes. This early example of adaptive reuse helped to maintain the Back Bay’s uniform appearance.

Today, it’s easy to understand why the Back Bay is one of America’s most desirable neighborhoods. Newbury Street, Boylston Street, and Commonwealth Avenue are lined with unique shops, trendy restaurants, and vintage homes, making the Back Bay an extremely fashionable destination for Boston residents and visitors. In fact, it’s not uncommon to spot celebrities strolling up and down these picturesque streets. This bustling neighborhood also houses the two tallest members of Boston’s skyline, the Prudential Center, and the John Hancock Tower, in addition to architectural treasures such as Trinity Church and the Boston Public Library, the first public lending library in the United States.

Beacon Hill: A 19th-century residential area north of Boston Common, Beacon Hill is named for the location of a beacon that once stood here atop the highest point in central Boston. Beacon Hill is now topped by the gleaming gold dome of the State House. Stroll this charming half-square-mile neighborhood filled with townhomes and mansions, to discover a delightful maze of red bricked sidewalks and cobblestone streets with working gas lamps, local boutiques, popular restaurants, and quaint B&Bs.

Winding along the north slope of Beacon Hill is the Black Heritage Trail, which explores the history of Boston’s 19th century African-American community. Highlights along the 1.6 mile trail include: The African Meeting House (1806) – the nation’s oldest existing black church built by free black Bostonians; the Abiel Smith School (1835) – the first public school for black children; and the Hayden House, an important station on the Underground Railway for escaping slaves.

Downtown Crossing: Shoppers can browse for Boston keepsakes, one-of-a-kind gifts and the latest fashions along this bustling pedestrian mall at the intersection of Summer and Washington Streets. Some of Boston’s oldest landmarks can be found here, such as the 19th-century Old South Meeting House, where a meeting of more than 5000 colonists resulted in the Boston Tea Party of 1773.

South End: The historic South End has the largest Victorian brick row house district in the nation, and has recently emerged as a vibrant urban center with fabulous art studios, experimental theaters and independent boutiques and restaurants. Explore it on foot to discover community garden plots, tiny bakeries and some of the city’s best dining.

Fenway/Kenmore Square: While this neighborhood may best be known as the home of the Red Sox and Fenway Park, it is also one of Boston’s academic and cultural hubs. Nearly a dozen of the 70 colleges and universities located in the area can be found here giving the neighborhood an unmistakably energetic feel. Not far from Kenmore Square, you’ll find the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Museum of Fine Arts and Symphony Hall.

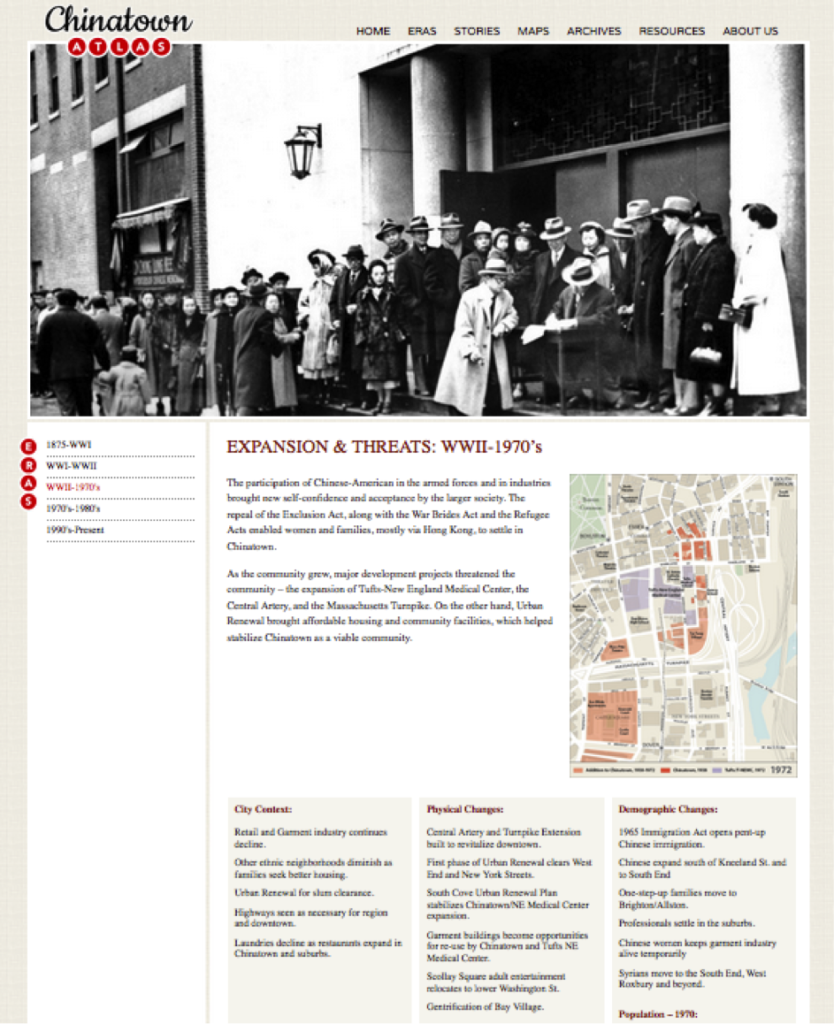

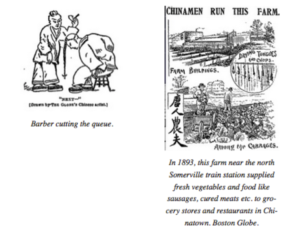

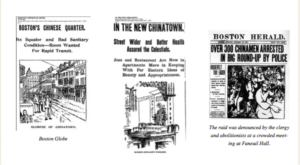

Chinatown: Boston’s Chinatown is the third largest Chinese neighborhood in the country. Renowned for its concentration of restaurants, Chinatown’s converted historic theaters now serve up decadent dim sum feasts. Beyond the neighborhood’s elaborately decorated gate, stroll the alleys for herbal shops, barbecues and Asian markets stocked with vegetables and spices. During the Chinese New Year and August Moon Festival, the streets are filled with dancing dragons, traditional music, and martial arts demonstrations.

Theatre District: Boston’s Theater District hosts an endless array of Broadway shows. Productions at the Colonial Theatre, Opera House Boston, along with the Citi Performing Arts Center, attract theatergoers of all ages. Bordering Chinatown, the area is also home to dozens of restaurants and bars offering fare in a wide range of prices. From Chinese to Thai to upscale contemporary American cuisine, the area is the ideal place for a pre-show meal.

The North End: With dozens of eateries serving homemade pasta, fresh bread, imported olive oil, cannoli, and cappuccino, the North End is infused with the flavor of its rich Italian history. Colonial-era sites are hidden throughout the neighborhood including Paul Revere’s house, the Old North Church, and Copp’s Hill Burying Ground. The North End comes alive in the summertime with feasts, festivals, and processions.

South Boston Seaport District: Boston’s waterfront is a vibrant mix of residential condos, marinas, hotels, artists’ lofts and restaurants. The city’s Institute of Contemporary Art is an architectural masterpiece overlooking the harbor. Nearby, the newly renovated Boston Children’s Museum invites your inner child to enjoy and explore the world around you. The Boston Convention & Exhibition Center also calls the Seaport District home, as does the Seaport Hotel & World Trade Center.

Cambridge: Just a bridge away across the Charles River, MIT and Harvard University help create the progressive flavor of Cambridge. Often referred to as Boston’s Left Bank, it’s the spirited, slightly mischievous side of Boston and has an atmosphere and attitude all its own. Packed with youthful vitality and international flair, it’s a city where Old World meets New Age in a mesmerizing blend of history and technology.

As a captivating, offbeat alternative to Boston’s urban center, the “squares” of Cambridge are charming neighborhoods rich in fine dining, eclectic shopping, theaters, museums and historical sites. Each square is a vibrant, colorful destination with a personality all its own, offering a unique selection of everything from restaurants, shopping, and music to technology and innovation.

As the East Coast’s leading hub for high-tech and biotech, Cambridge has a creative, entrepreneurial spirit. With over 3,000 hotel rooms, Cambridge is also a popular destination for professional meetings and conferences, offering the largest hotel inventory in New England outside of Boston.

Cambridge is the birthplace of higher education in America. Harvard College was founded in 1636, and across town, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is known as the epicenter of cyberculture. Both universities house renowned museum collections and tours that are open to the public.

Beyond Boston: In addition to everything within the city limits, some of Massachusetts’ most scenic and historic towns are just a short distance from the city center. There are sights to see at every turn.

North of Boston: The charm and lure of the sea draw visitors north. The oceanside town of Winthrop is minutes from downtown Boston. Winthrop’s beaches are popular destinations for festivals and special events throughout the summer.

Five miles from the heart of Boston is a magnificent three-mile stretch of unbroken shoreline in Revere. Sea lovers stroll along the beautiful salt-water marshes and look forward to the annual Sand Sculpting Festival in July.

Nearby, historic Salem is one of the country’s oldest cities, with streets retaining an 18th-century charm. Sites to visit in Salem include The House of the Seven Gables, a National Historic Landmark forever immortalized by author Nathaniel Hawthorne, the Peabody Essex Museum, a museum of international art and culture housing one of the best Chinese art collections outside of China, and the Salem Witch Museum, where you can experience the Salem witch trials of 1692.

Whale-watching expeditions and harbor cruises are popular activities in the Cape Ann towns of Gloucester and Rockport. Both feature fine seafood restaurants, art galleries, and small inns.

Lowell, in the heart of the Merrimack River Valley, was home to the American Industrial Revolution and famed author Jack Kerouac. Lowell’s Heritage State Park and National Historic Park and the Lowell Folk Festival in July should not be missed.

South of Boston: With its close proximity to Boston (eight miles away), convenient access to major highways and public transportation, as well as numerous historic sites and attractions, the town of Quincy is ideally situated to host meetings, conventions, and large tour groups.

Quincy is the birthplace and summer home of presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams. It also the shops and restaurants of picturesque Marina Bay and nearby destinations for rock climbing and harbor cruises.

An hour’s drive from Boston, Plymouth offers a resort-oriented seaside setting with 21 miles of coastline and a small-town feel. It has become a popular tourist stop and a great destination for meetings and conventions. Visitors can enjoy championship golf courses, whale watching, sailing, and shopping. This is also the place to find attractions such as Plimoth Plantation and the Mayflower II, a full-scale reproduction of the original Pilgrim ship. From now through 2020, Plymouth will be celebrating Plymouth 400, the 400th anniversary of the 1620 Mayflower voyage, the landing of the Pilgrims and the founding of Plymouth Colony.

Just a little further south of Boston is Battleship Cove in Fall River, a maritime heritage museum featuring the world’s largest collection of historic naval ships including the Battleship U.S.S. Massachusetts. Nearby is the New Bedford Whaling Museum, celebrating the region’s rich whaling history.

Also South of Boston are Cape Cod and the islands of Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard. This area has become a haven for those who seek the peaceful inspiration of natural seaside beauty. Visitors can savor the local seafood delicacies and enjoy excellent beaches. For those looking for something a little more active, fishing, golf, antiquing and shopping abound.

Though the Cape is a world apart from many other destinations in its charms and services, it lies within easy reach of Boston’s Logan International Airport, just 50 miles away. Local flights from Boston to Hyannis are available as well as excellent bus transportation and limousine service. The tip of Cape Cod, Provincetown, can be accessed from Boston on a high-speed ferry that takes only 90 minutes.

Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket can be reached by ferry from Woods Hole and Hyannis. Air transportation is available from Boston, New York City and several Cape towns to both islands’ airports.

West of Boston: The picturesque towns of Lexington and Concord complement any visit to the Boston area. It was on Lexington Green, in the early morning hours of April 19, 1775, that Captain John Parker of the Colonial Militia announced, “Don’t fire unless fired on. But if they mean to have a war, let it begin here.” Those words and the battle that followed changed the course of history.

Sites to visit in Concord include The Old Manse, Old North Bridge, and the Concord Museum. The Concord Museum has been collecting American artifacts since before the Civil War and features treasures including the “one, if by land, and two, if by sea” lantern immortalized by Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride.”

Additional sites west of Boston include Waterworks Museum, the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum and historic Old Sturbridge Village, which brings 19-century New England back to life. Visitors can also go skiing at Wachusett Mountain from late November through early April.

New England: If you were to draw a two-hour circle around Boston, you’d hit all six New England States. Visitors to Boston find that once they are here, it’s easy to get around by train or car to visit the other states that comprise this great region.

Once the showplace of opulence for New York’s high society, today’s visitors to Newport, Rhode Island, can tour its Gilded Age mansions and gardens, shop along the waterfront or enjoy the holidays with re-creations of Victorian parties and concerts. This modern and sophisticated seaside town is just one-and-a-half hours from Boston.

Mohegan Sun Casino in Connecticut is a major destination for glitz and gaming. This hot spot offers slot machines, poker, and blackjack, live entertainment, lounges, hotels, shopping and more. The casino is located two hours southwest of Boston by car, and can also be reached by bus or train.

From the quaint towns of Ogunquit and Kennebunkport to the cosmopolitan flair of Portland or Freeport with its designer outlets and LL Bean flagship store, visitors can explore timeless villages, antique or outlet stores and numerous beaches in Maine.

New Hampshire offers visitors the charm and history of Portsmouth, a rich arts-and-culture scene, and exciting mountain skiing adventures. From the capital city of Burlington on Lake Champlain to small towns and villages, Vermont offers visitors outdoor adventures and artisan experiences.

Courtesy www.bostonusa.com.

Nearly all geographers are concerned about human rights, and in their personal and professional lives seek meaningful ways to act on these concerns and values. The AAG and the discipline of geography intersects with human rights in numerous ways. This special theme within the 2017 AAG Annual Meeting will explore intersections of Human Rights and Geography, and will build on the AAG’s decade-long initiatives on Mainstreaming Human Rights in Geography and the AAG. An Interview with Noam Chomsky by Doug Richardson will keynote this theme at the 2017 Boston Annual Meeting.

Nearly all geographers are concerned about human rights, and in their personal and professional lives seek meaningful ways to act on these concerns and values. The AAG and the discipline of geography intersects with human rights in numerous ways. This special theme within the 2017 AAG Annual Meeting will explore intersections of Human Rights and Geography, and will build on the AAG’s decade-long initiatives on Mainstreaming Human Rights in Geography and the AAG. An Interview with Noam Chomsky by Doug Richardson will keynote this theme at the 2017 Boston Annual Meeting.

AAG Past President Sarah Witham Bednarz will explore the evolving role, nature, and relevance of geography education as viewed by former presidents of the AAG from 1910 to the present. AAG presidential addresses have, at times, commented directly on education issues; at other times the topic has been avoided, if not ignored. What changes have occurred over time in how geography education is perceived and valued? What persistent educational concerns has the discipline wrestled with? How has the discipline, represented by its leaders, addressed broader social, cultural, and political factors that affect the production of new geographic knowledge and the reproduction of geographers?

AAG Past President Sarah Witham Bednarz will explore the evolving role, nature, and relevance of geography education as viewed by former presidents of the AAG from 1910 to the present. AAG presidential addresses have, at times, commented directly on education issues; at other times the topic has been avoided, if not ignored. What changes have occurred over time in how geography education is perceived and valued? What persistent educational concerns has the discipline wrestled with? How has the discipline, represented by its leaders, addressed broader social, cultural, and political factors that affect the production of new geographic knowledge and the reproduction of geographers?