Stories of Change Hidden in Washington, D.C.’s Alleys

Washington, D.C. is known for its monuments, museums, and grand government buildings. It is associated with policy wonks, foreign dignitaries, and political controversy. But it is also a home town for thousands of people who live in its lively neighborhoods. How best to get a glimpse of everyday life for D.C.’s residents, those people living in places hidden from view on the National Mall? A tour of the city’s most hidden places of all: its urban alleys.

Washington, D.C. is known for its monuments, museums, and grand government buildings. It is associated with policy wonks, foreign dignitaries, and political controversy. But it is also a home town for thousands of people who live in its lively neighborhoods. How best to get a glimpse of everyday life for D.C.’s residents, those people living in places hidden from view on the National Mall? A tour of the city’s most hidden places of all: its urban alleys.

Like many American cities, D.C. has a system of alleys. Most of these narrow thoroughfares are used for municipal functions such as garbage collection, deliveries, and parking. You might also find more informal, but not unexpected, signs of use, like basketball hoops or folding chairs used by those who live, work, or spend time nearby. Yet a turn down the right alley in D.C. might surprise you. In D.C. alleys you’ll find clues about the city’s history of substandard housing for African American migrants following the Civil War, you’ll see evidence of the early roots of gentrification in the 1950s, you’ll glimpse a burgeoning public art scene, you’ll tread across new wastewater management projects, you’ll stumble upon a community garden, or you’ll even find yourself in a hip and expensive commercial enclave. D.C.’s alleys offer insight into how this city has dealt with its long history of strained race relations, how it is creatively managing urban space to sustainably support urban growth and density, and how it is attempting to stay true to its longtime African American and Latinx residents while attracting whiter, younger, and wealthier residents who have flooded the city in recent years.

Even prior to the Civil War, D.C.’s alleys told a unique story. As the city’s population increased in the 1850s, alleys were cut from the city’s large blocks to provide access to residential space in block interiors. These new alleys often formed I or H shapes, with only narrow outlets to main streets, and they were called “hidden” or “blind” alleys because the activities inside could not be seen from front streets. As sites of makeshift wood-framed housing, these alleys were where black and white residents found inexpensive places to live downtown. As opposed to other Southern cities that had alley housing, in which a servant or slave house along the alley would share a lot with the main house, to which it would be oriented, the residents of D.C.’s blind alleys were disconnected from the residents of the front streets; their homes were on separate lots and they were oriented to the back alley. In fact, alley-facing lots and front street-facing lots were often separated by other narrow alleys or by fences. D.C.’s alley residents were legally and socially removed from life on front streets.

During and immediately following the Civil War, the city faced a severe housing shortage as the population nearly doubled. Growth of the African American population was particularly profound as freed people flooded the city. Between 1860 and 1870, the black population more than tripled from 14,000 to 43,000. In a pedestrian city without mass transportation, these migrants were forced to live close to employment downtown. As historian James Borchert has detailed, many individuals and families found shelter in the makeshift housing, and later brick row houses, constructed in the blind alleys, which became increasingly overcrowded. The lack of adequate sewerage systems, clean water, and waste disposal also caused high rates of disease and death. Crucially, the overcrowding was not just due to an increase in population. Absentee owners of alley properties recognized the high demand for shelter and increased rents. This in turn led to more density as families were forced to double up in order to pay rent.

D.C.’s alleys were racially segregated, and whereas the majority were all-white before the Civil War, by 1897, 93% of alley dwellers were African American. Borchert argues extensively that through the first decades of the twentieth century, despite the real dangers of disease, death, and poverty, African American alley residents in D.C. valued their communities. Many were newly adjusting to urban life from being enslaved on Southern plantations, and they created incredibly close-knit, alley-based communities rooted in extended kinship networks and communal help. They treated the alley itself as communal property where children could play, adults could socialize and exchange goods, and neighbors could warn one another about outsiders—particularly white outsiders like police or social reformers—who might enter the alley. Alleys also had exceptionally high retention rates given high population turnover in other cities at the time, and especially because alley dwellers did not own their own homes. In alleys, African Americans made claims to the city.

For those living in alleys, they were places of African American identity and belonging, where necessity reinforced strong communities based on kinship and mutual aid. White Progressive-Era reformers and elites also understood alleys as African American urban space, but for them this had only negative connotations. They published studies reporting on the high rates of disease, death, poverty, and crime in alley dwelling communities, and they generally concluded that the isolated built environment of blind alleys fostered immorality. Findings like these ignored or were oblivious to the positive associations of community or mutual aid that were so central to life for alley residents. Instead, they popularized perceptions of alleys as African American slums.

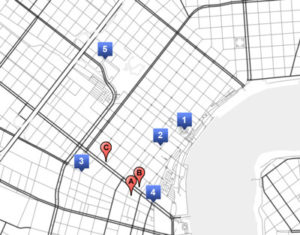

By the 1950s, young professionals, nearly all whom were white, were moving to Washington, D.C. to work for the growing federal government, and these new Washingtonians wanted to live near their workplaces. It was in the 1950s that developers set out to transform downtown Washington, D.C. neighborhoods—those with alley dwellings—into elite white enclaves. In the Southwest neighborhood, this process occurred with federal urban renewal funds, and Southwest’s many alley dwellings were the first to be demolished in the now-notorious clearance of Southwest, which resulted in the displacement of 23,000 of its residents. In neighborhoods like Capitol Hill, Georgetown, and Foggy Bottom, small-scale developers bought alley dwellings, evicted African American tenants, rehabilitated the homes, and sold them to young white professionals, facilitating the transition of these D.C. neighborhoods from mixed-race and mixed-income to nearly entirely upper-middle-class and white. Not called gentrification at the time, the process of displacement, rehabilitation, and resale foreshadowed demographic change that would sweep entire neighborhoods in the 1970s and again in the present day. By the end of the 1950s, alley dwellings were no longer classified as slums, and these low-rent African American communities disappeared from D.C.’s landscape. Yet the built environment persists; turn down alleys such as Snow’s Court in Foggy Bottom, Pomander Walk in Georgetown, or Brown’s Court in Capitol Hill (to name just a few) and you’ll find the narrow nearly-million-dollar rehabilitated rowhouses that once housed the city’s poorest African American residents.

As Washington D.C.’s alley dwellings disappeared due to demolition and rehabilitation in the 1950s, so did the public perception of inner-city alleys as African American community and residential space. By the 1960s, as in the rest of the country, D.C.’s alleys were primarily known as service corridors whose formal functions included vehicle storage and waste collection. In this period of postwar white flight and urban disinvestment, however, alleys also filled with garbage and teemed with rats. By the 1980s, alleys were too often associated with the drug trade and horrific gun and sexual violence. Alleys became symbols of decline in America’s cities, which, compared to growing suburbs, were disproportionately African American, underfunded, and underserviced.

Today, as many U.S. cities have seen the reversal of white flight as investment and young professionals have flooded downtown neighborhoods, some cities, including D.C., are turning again to their alleys. These overlooked and long-neglected public spaces seem to be the solution for the myriad puzzles facing growing cities. D.C.’s Department of Transportation, for example, has instituted a Green Alleys program to combat wastewater runoff; walk down an alley in the residential neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city and you’ll find new permeable paving. The city’s 2016 zoning rewrite now allows for dwelling units to be built along alleys in certain residential zones in an attempt to add density and more affordable housing to the city’s downtown; walk through some back alleys in Capitol Hill and you’ll see new construction of alley-facing houses (this move to put residences back in alleys would have Progressive-Era reformers stunned).

Alleys even provide an antidote for D.C. residents now frustrated by the effects of recent investment. Those disillusioned by the ubiquity of glass-paneled luxury apartment buildings and mixed-use developments can turn down alleys for a seemingly more authentic city scale. Alleys promise a labyrinth space where one can wander and discover. They remain in people’s imaginations the edgy, dirty, and potentially dangerous parts of a newly glitzy city. And of course, this edginess and “frontier” quality can be capitalized upon as well. Enter Blagden Alley in the Shaw neighborhood, and you’ll find high-end restaurants, a boutique coffee shop, and design firms, accessible only through the alley. Even if you confirm the locations on Google Maps before you go, you’ll still have to trust your sense of direction as you pass a surface parking lot, dumpsters, delivery trucks, and strewn garbage on your way to the center of one of the city’s last remaining nineteenth-century “blind alleys.” In Blagden Alley you’ll also find the “D.C. Alley Museum,” an officially christened collection of alley murals (alley murals, not part of the “museum,” abound in the Shaw/U Street area). While these murals don’t have the defiance of graffiti tags—they are in fact funded by the D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities—they still give the illusion of artists appropriating the surfaces of private property. Blagden Alley offers a partially curated aesthetic that serves as an antithesis to the large-scale development that now swaths the downtown core.

D.C.’s alleys have, at the moment, found a tenuous balance between longtime uses and new investment: in Blagden Alley and nearby Naylor Court, garbage trucks trundle past professionals eating at high-end restaurants; rats scurry beneath Instagram-ready murals; and prostitution and drug use take over the alleys by night, while families living in restored alley dwellings set up block parties by day. You might lament the late gentrification of these alleys, the last holdouts in a larger area that’s already thoroughly gentrified. Or, you might enjoy an urban space that manages to attract racially and economically diverse groups of people. At least for now, you would be right to think so either way. Alleys offer a glimpse of life in this city in transition.

Rebecca Summer is a Ph.D. candidate in the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s department of geography. Learn more at www.rebeccasummer.net. She can be reached at rsummer [at] wisc [dot] edu.

The research reported in this article was supported by an award from the National Science Foundation, BCS-1656997.

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0041

Recommended reading:

Ammon, Francesca Russello, “Commemoration Amid Criticism: The Mixed Legacy of Urban Renewal in Southwest Washington, D.C.” Journal of Planning History 8 no. 3 (2009): 175–220.

Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove, Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

James Borchert, Alley Life in Washington: Family, Community, Religion, and Folklife in the City, 1850-1970 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1980).

District Department of Transportation, “Green Alley Projects,” https://ddot.dc.gov/GreenAlleys

Mark Jenkins, “Murals and mosaics enliven an already bustling Blagden Alley,” The Washington Post, December 29, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/goingoutguide/museums/murals-and-mosaics-enliven-an-already-bustling-blagden-alley/2015/12/29/6a9917f4-a991-11e5-9b92-dea7cd4b1a4d_story.html?utm_term=.70994c52ee3f

Kathleen M. Lesko, Valerie Babb and Carroll R. Gibbs, Black Georgetown Remembered: A History of its Black Community from the Founding of “The Town of George” in 1751 to the Present Day (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2016).

Dan Reed, “Even D.C.’s Alleys Are Thriving,” The Washingtonian, March 9, 2017, https://www.washingtonian.com/2017/03/09/even-dcs-alleys-thriving/

On September 24, 2016, thousands gathered on the National Mall to celebrate the grand opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The building is distinctive: the bronze-meshed ziggurat moves upwards towards the sky and into the light. Inside the new 400,000 square foot museum are some 36,000 artifacts that share truths about America’s past and tell stories about 400 years of of black life in America. The new museum allows Americans to walk the path from slavery to civil rights to the Black Lives Matter movement.

On September 24, 2016, thousands gathered on the National Mall to celebrate the grand opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The building is distinctive: the bronze-meshed ziggurat moves upwards towards the sky and into the light. Inside the new 400,000 square foot museum are some 36,000 artifacts that share truths about America’s past and tell stories about 400 years of of black life in America. The new museum allows Americans to walk the path from slavery to civil rights to the Black Lives Matter movement.

The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial represents a significant departure from other memorials on the Mall. It is the first to commemorate an African American, and by extension, the first memorial to recognize and legitimize the modern Civil Rights Movement. Civil rights memorials are a litmus test for how far society has progressed towards the goal of racial equality and justice and to what degree society has fulfilled the Civil Rights Movement’s goals. And while there are many other memorials to Martin Luther King Jr. around the country, the MLK Memorial on the Mall confers a national legitimacy on the Civil Rights Movement and its objectives.

The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial represents a significant departure from other memorials on the Mall. It is the first to commemorate an African American, and by extension, the first memorial to recognize and legitimize the modern Civil Rights Movement. Civil rights memorials are a litmus test for how far society has progressed towards the goal of racial equality and justice and to what degree society has fulfilled the Civil Rights Movement’s goals. And while there are many other memorials to Martin Luther King Jr. around the country, the MLK Memorial on the Mall confers a national legitimacy on the Civil Rights Movement and its objectives.