The More-Than-Conference Conference

I was surprised to see the line snaking around the entrance to the Past President’s Plenary at this year’s AAG conference in Tampa. Of course folks wanted to hear Eric Sheppard’s address, I thought, but honestly the only lines I had seen at the conference ended at a ‘free drinks’ bar. Things became clearer as I approached: there were people standing at the entrance to the room handing out postcards, and so fellow geographers were lining up to get one; not wanting to miss anything I took all three. As it turned out, they made excellent reading material (see figs. 1-6). Each card provided verbal and visual information about aspects of the discipline and the academy in general that the Great Lakes Feminist Geography Collective found wanting. Just the day before I had attended a session of what is called the subconference where we had talked through related issues facing junior scholars working in the academy: lack of support for social reproduction, increasing use of contingent faculty, the enduring impacts of the great recession, and so on. There were I realized many different confer-ings going on at the conference, all in some way related to it but differing in type and scope.

Almost all conferences exceed what is listed on the program; social interactions among groups of people are never fully scripted. And what is commonly referred to as “the AAG” — a deceptively short and unassuming name for what often exceeds definition — is certainly no exception. Even the full title — the Annual Conference of the Association of American Geographers — just doesn’t seem adequate to describe the excitingly and dauntingly large, diverse, social, performative, professional and personal gathering that happens once a year in a large American city. Those of us who have attended “the AAG” know that it is much more than the 5,000 or so papers, posters and plenaries that are presented. There are workshops, field trips, receptions, preconferences, parties, meetings, in-the-hallway-chats, dinners, and drinks that merge our professional and personal lives. And there are “other” events too, those meant to provoke, protest, initiate, and investigate. Given that these activities often take place in the interstitial spaces of the conference and are not visible to everyone, I highlight them here because I believe they are important signs of the liveliness and dynamism of our discipline.

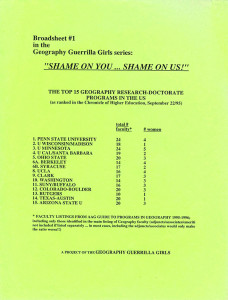

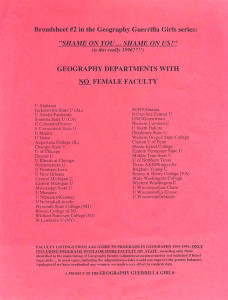

Like most political interventions, the idea of the postcard “drop” (as the Collective calls it) wasn’t born anew. From what I’ve gathered from my own memory and that of fellow geographers (I sent out a message on several listservs that reached about 4,000 geographers, asking for information about “other” activities that have occurred at our conferences; thanks to all of those who responded) there have been several instances in the past when individuals and groups have distributed protest literature. One geographer remembered Bill Bunge handing out anti-nuclear flyers at the door of a plenary session at the Detroit conference in 1985, and no doubt there have been similar interventions since then. The Collective’s website traces the “drop” to the action taken by a group of Canadian feminist geographers at the 2002 AAG conference. The group compiled statistics about the number of women in geography, printed the information on pink sheets, and distributed them throughout the conference, keeping the authorship anonymous. Reactions were mixed, they write, but the act of compiling information that vividly depicts inequities and distributing it widely had multiple effects. Six years before that, a similar intervention occurred at the Charlotte AAG conference, when an anonymous group called the Geography Guerrilla Girls distributed two broadsheets that documented the paltry number of women faculty in geography departments in the United States (see figs. 7, 8). So the Collective’s postcards drew on and were contributing to an interesting historical geography of the politics of Geography. At the same time, another contribution to that historical geography was being enacted in Tampa. Graduate students from the University of North Carolina — inspired they say partly by Antipode and the critical geographic inquiry it represents — had put together a zine on Black Geographies called The Whirlwind that they handed out to geographers attending related sessions on geography and race/racism, an important and lively addition to the discipline’s history of protest literature.

The subconference too draws on an historical geography of the politics of the discipline as geographers have sought alternative ways to gather and discuss issues not usually encountered in the official hallways and meeting rooms. For example, GPOW (Geographic Perspectives on Women specialty group) has organized a reception coincident with the AAG celebrating recently published feminist geography books at a local bookstore each year since 2005, creating alternative spaces for networking and collaboration close to the conference site but not in it. The idea of the subconference has its roots in several sets of discussions held at various venues, and took form for the first time in 2010 at the D.C. conference. Since then it has evolved into a series of sessions listed on the program but organized specifically not to follow the template of ‘regular’ sessions; instead, facilitators lead discussions geared to issues not often addressed (though certainly talked about) formally at conferences: work-life balance, child care, mental health, disabilities, contingent faculty, impacts of the recession, the neoliberalization of the academy. And word is out that about the need for this type of intervention: a group of MLA (Modern Language Association) members organized a subconference at their last meeting (make sure to read down the page to see the nice shout out to the subconference of the AAG!). A similar attempt to open alternative spaces for new types of conversations within the discipline was apparent in a set of sessions geared toward mental health issues, and in past years, a set of sessions on “deaf geographies.”

Other complementary sites that revolve around “the AAG” are geared toward opening the conference to different forms of expression. I have memories of past AAG hallways lined with carefully curated photographs, but I can’t seem to find information about who or what organized these exhibitions. In Los Angeles a group of geographers organized an art exhibition called “Curating the Cosmos” that accompanied a series of sessions with the same title, making important interventions into understanding what the geohumanities might look like, while another geographer created an on-site maze as a form of impromptu landscape art (see fig. 9). And for the past three years a group of geographers have coordinated a four-hour map-a-thon mash-up that is held in conjunction with the AAG but at a different site, thus encouraging creative digital cartographic expression and inventing new arenas for networking and community building.

No doubt this is a partial and selective accounting of the many “other” activities that coincide with our annual conference (and I would love to hear about more). I hope that highlighting these few interventions suggests the importance of the more-than-conference aspect of our conference, of the ways that “the AAG” provides a platform for self-critique and creative intervention, and of how these provocations and investigations keep the discipline dynamic and create space for changing its contours. These are signs of the liveliness of our discipline, of people and communities who care enough to prod and poke us. I look forward to hearing about other interventions and experiencing them in Chicago and beyond.

— Mona Domosh