Will we avert geography’s ‘trans failure?’

“…geography’s trans failure is a problem because geography is missing out on our amazingness!”

—Sage Brice (2023, p. 593)

By Eden Kinkaid

It was Friday night when I saw the news. The Governor of Ohio had just made an announcement that the state would be revising the protocols for accessing trans healthcare. This time it wasn’t for youth (though they were dismantling that too); it was for adults, making Ohio the second state to take measures to restrict adult care. The Governor was now proposing to change the administrative rules at the Ohio Department of Health — against all serious medical and professional opinion — to make trans care more difficult to access, regardless of your insurance. The Governor said it was for our protection, though a month later a broadcasted conversation between Ohio and Michigan GOP lawmakers said the quiet part out loud: the endgame was to end trans healthcare access for everyone.

Every day I see news like this. In the first month of 2024, 431 anti-trans bills have been introduced around the country. Many of these bills will become laws: laws targeting trans youth, laws regulating which bathroom we can legally access, laws that would legally punish us for “fraud” for diverging from our sex assigned at birth, laws that are ending the legal recognition of trans people in this country. This news seems to never stop and shows no signs of stopping anytime soon. As a trans person, I have learned to compartmentalize it, to become desensitized to it, to register the information but not to feel it. But this news hit differently.

It hit hard because I was preparing to fly out for a campus interview in Ohio on Sunday morning, in 36 hours. It was, in many senses, a dream school for me, one that aligned with my pedagogical vision and my values. The majority of the student body identified as queer. I got the sense that it could be a place for me, a reprieve from the intellectual and emotional labor of making myself legible to my colleagues and my institution. I thought it was the kind of institution that might know how to recognize and value me, both as an intellectual and as a human being.

But in an instant, my hope in the prospect collapsed. I knew that flying across the country and interviewing all day would be exhausting and ultimately futile. I went anyway, holding onto the vague hope that the new rules might not come to pass, or if they did, that the bigger clinics might survive and manage to maintain access. No one knew what was going to happen. And I knew there would be no way to know if I could access care by the time I would have to make a decision. Would I knowingly move to a state that had announced its intentions, and begun taking steps, to eliminate me?

The interview went really well. I felt present and at ease, despite the existential static occupying my mind and body. At the end of the day, I sat in the Dean’s office for the final interview of the visit. Our conversation felt unusually deep and intimate; there was no question in either of our minds that I belonged there. “What would it take for you to see a future for yourself here?” he asked. “There is only one problem,” I told him, “I am not sure if I can live in your state.”

A couple weeks later I would have another interview, this time in Missouri, which wasn’t looking much better. During the week of the interview, the legislature was entertaining eight bills in a special legislative session focused solely on “transgender issues.” (Activist Alok Vaid-Menon clarifies that there are no such thing as “trans issues:” “There are just issues that nontrans people have with themselves that they are taking out on us.”)

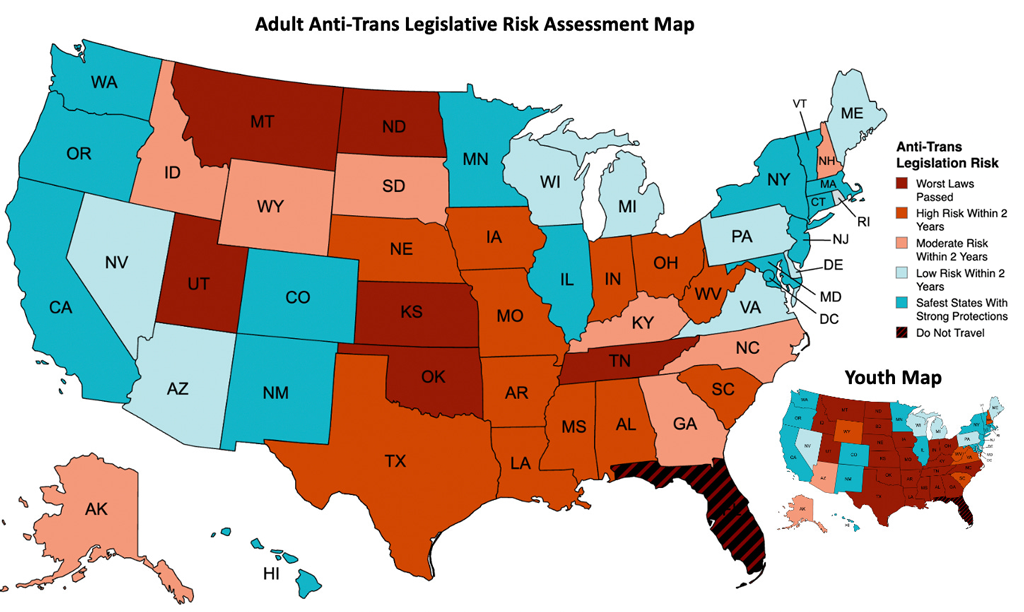

I anxiously scrolled through news articles online, deciphering various maps indicating which states were safe and which weren’t. Missouri was headed in a bad direction, but St. Louis was across the river from Illinois, which could be safe, at least for now.

The position would only be for two years. I thought maybe I could outrun it. But I could not ignore the fact that the doors to my career were slamming shut like dominos falling, day after day, bill after bill, state after state.

* * *

Anyone who has spent any time in academia understands the difficulties of the academic job market. You don’t get to choose where you end up. Maybe you have to move around for a while, maybe you have to take a less than ideal temporary position on your way to a stable career.

I had more or less accepted this fact; my passion for geography overruled the inconveniences of building an academic career. I always thought it would work out some way or another. Yet as my job search intersects with a rising tide of anti-trans legislation, I’m no longer sure it will. The obstacles are too much: exhausting, demoralizing, overwhelming. As Sage Brice describes:

repeatedly uprooting our lives and relocating for short-term insecure contracts is a challenge for anybody. But it hits particularly hard when at each new juncture you have no idea whether or when you will be able to access healthcare, housing, or even just safe access to toilets in the workplace. When you do not know if you will encounter hostility from your institutional leadership, or in the labour union that is supposed to protect you. When your employers host public speakers who agitate against your basic human rights and dignity. When you know you might wake up one morning — any morning — to find yourself splashed over the front page of a right-wing tabloid, the next hack-job victim in a raging culture war. When it might take months or even years to find other trans and nonbinary colleagues in your workplace, by which time you will likely be leaving again. (2023, 595).

That’s what we are up against. The invisiblized yet momentous barriers most of my colleagues have never even had to perceive, let alone navigate.

[We are up against] invisiblized yet momentous barriers most of my colleagues have never even had to perceive, let alone navigate.

The problem is that this career path assumes the mobility of scholars, especially those early in their career. Trans people’s mobility is increasingly limited, whether it be by access to healthcare or other discriminatory legislation, or just the fatigue of having to renegotiate care at every turn. It assumes material resources, which, statistically, trans people tend not to have (29% of trans adults live in poverty, compared to 16% of their cis-hetero counterparts. 38% of Black trans adults and 48% of Latinx trans adults live in poverty). It assumes a level of social and emotional resilience – which trans people certainly have — but which is difficult to access when you face compounding forms of precarity, violence, discrimination, and structural impossibility; when your literal right to exist is being targeted every single day by people and processes that you have no control over.

Weathering these obstacles to build a career here requires a sense of belonging and support in this discipline. Yet one faces further obstacles within the spaces of geography. As I and others have described, geography is deeply cisheteronormative and transphobic (Gieseking 2023, Kinkaid et al. 2022, Kinkaid 2023, Rosenberg 2023).

Forging ahead regardless requires hope. Yet as I take a clear-eyed look at the discipline I love, the career I dream of, I wonder if there is any reason to have hope.

* * *

My hope falters on the reality that the current discourse and practices of ‘trans inclusion’ in geography are so out of step with the escalating precarity of trans life in the U.S. and elsewhere (see Todd 2023) that they do not mean much. Over the years I have grown increasingly fatigued by trying to educate my colleagues about basic concepts like pronouns and everyday transphobia, concepts I need them to understand — things I need them to take responsibility for — so that I can have a career here, so that I can stay here. The rate of uptake is slow, and the resistance in many quarters is surprisingly high. I’m starting to wonder if it is true, the message I’ve been getting all along: that people like me simply do not belong here (Kinkaid 2023b).

Reflecting on my time in geography, I wonder: Why has it been my responsibility, as a transgender graduate student, to do this work? Why do I have to perform this intellectual and emotional labor in order to access a baseline of professional dignity and recognition here? If I do not do this work, who will make and hold space for those who will come after me?

I wonder if I am wasting my energy trying to activate my colleagues into caring, into taking action. When they cannot be bothered to go to a single workshop, to pick up a single book on trans life, to speak up for me even in the most obvious cases of transphobic bias and discrimination, how can I ever expect them to fight for me? To fight for my life?

I am afraid that the time for such appeals is running out. If there is to be a future for trans people in geography, we must take immediate and bold action to ensure that future is possible. Now the struggle is not only about departmental climates and trans ‘inclusion’ or ‘belonging’ (though that matters too) — it is quickly becoming about trans survival within and beyond the halls of the academy.

It is about making geography a home for trans people, making geography a place to imagine trans futures and affirm trans life. It is about activating our stated commitments to justice, to advocacy, to critical knowledge, to cultural critique, to transformational change. No amount of cutting-edge scholarship, no amount of diversity training — however well-meaning — will get us there. We must address the compounding forms of material and political precarity trans colleagues face if we are to have the luxury of a future here. And we must do it now.

The AAG and our departments must take immediate and meaningful action to ensure that future if we are truly committed to social justice and inclusion.

The AAG and our departments must take immediate and meaningful action to ensure that future if we are truly committed to social justice and inclusion. What might that look like? It would require departments in relatively ‘safe’ states using every tool at their disposal — including targeted hires — to attract and retain trans scholars. The AAG can utilize its existing networks with department heads to educate and advocate around this issue. We must do this now, as pipelines for underrepresented faculty are under threat as DEI becomes a target of legislators.

It would mean putting material resources and institutional weight behind mentorship programs specifically serving trans geographers, not only to affirm our ‘belonging’ but to develop networks through which we can find advocates and achieve some measure of career security to rise above the engulfing forms of precarity that shape our lives and too often lead to our deaths.

It would require asking our trans students and colleagues: “What would it take for you to see a future for yourself here?” and being ready to listen very carefully. This question is not a light or casual one — it is freighted with the existential weight that burdens our lives and forecloses the possibility of those lives, the weight that stops us from even being able to imagine the future (Malatino 2022). If we are to ask this question — which we must — we must be prepared not only to listen, but to commit ourselves to action. The current “trans moment” (Brice 2023, 592) requires nothing less of us. Let us do it now, before it is too late.

Acknowledgements: A heartfelt thanks to Nick Koenig, Lindsay Naylor, and Wiley Sharp for their feedback on this article.

Works cited

Brice, S. (2023). Making space for a radical trans imagination: Towards a kinder, more vulnerable, geography. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 41(4), 592-599.

Gieseking, J. J. (2023). Reflections on a cis discipline. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 41(4), 571-591.

Kinkaid, E. (2023). Whose geography, whose future? Queering geography’s disciplinary reproduction. Dialogues in Human Geography, 20438206221144839.

Kinkaid, E. (2023b). The Feminist Killjoy Handbook: Sara Ahmed. Dublin, Ireland: Allen Lane, 2023. 323 pp., notes, bibliography, index.£ 20.00 paper (ISBN 978-1541603752).

Kinkaid, E., Parikh, A., & Ranjbar, A. M. (2022). Coming of age in a straight white man’s geography: reflections on positionality and relationality as feminist anti-oppressive praxis. Gender, Place & Culture, 29(11), 1556-1571.

Malatino, H. (2022). Side Affects: On Being Trans and Feeling Bad. University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis.

Rosenberg, R. (2023). On surviving a cis discipline. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 41(4), 600-605.

Todd, J. D. (2023). Trans Liberation in the UK is Under Threat: How Geographers Can Respond.” Antipode Online. https://antipodeonline.org/2023/05/24/intervention-trans-liberation-in-the-uk/

Perspectives is a column intended to give AAG members an opportunity to share ideas relevant to the practice of geography. If you have an idea for a Perspective, see our guidelines for more information.