Some Hispanic and Latino Landscapes of New Orleans

If you have a penchant for landscape, be warned: you will be tempted to spend more time outside of the hotels than in the paper sessions of the upcoming AAG conference in New Orleans. Many aspects of the New Orleans landscape might seem generically American, especially within the compact Central Business District (CBD) upriver from Canal Street, where the conference hotels are located.[1] The CBD and adjoining, gentrified Warehouse District do retain some fine examples of nineteenth- and twentieth-century architecture. But venture downriver, across Canal Street into the French Quarter, and you will enter an urban landscape that remains more attuned to the Mediterranean and Caribbean than the North Atlantic, as A. J. Liebling pointed out half a century ago in The Earl of Louisiana. Those interested in the Hispanic and Latino aspects of this compelling landscape might consider the following sampling of spots to visit, mainly oriented toward the city’s historic status as a Spanish colonial capital and U.S. neo-colonial entrepôt for Latin America. For more contemporary Latino and Hispanic landscapes, you will mainly have to venture into neighboring Jefferson and Saint Bernard Parishes.[2]

For a first, convenient stop among the sampling of spots to appreciate this particular dimension of the urban landscape, simply begin two blocks upriver from the Sheraton, at the corner of Saint Charles Avenue and Union Street in the CBD.[3] There the headquarters of the infamous United Fruit Company has become a bank, the company long since defunct. But during the early twentieth century, from behind the unforgettable façade of fruit laden cornucopia spilling down from the cornice of the ornate entrance, Sam “The Banana Man” Zemurray controlled the main flow of bananas into the U.S. from plantations in half a dozen countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (Figure 1). La Frutera or El Pulpo, as Latinos variously referred to the company, controlled everything in its supply chain from the banana trees to the White Fleet freighters that carried them, as well as the politics of the Central American countries that thereby became known as banana republics. The White Fleet has also persisted in a way, although no longer steaming up the Mississippi River with loads of bananas and Honduran immigrants; instead, you will see its name and pennant emblazoned on the doors of one of the city’s fleets of taxis.

Two blocks further upriver along Saint Charles Avenue, crossing Poydras Street toward the Warehouse District, now being rebranded as the Arts and Museum District, Lafayette Square invites relaxation in the largest greenspace near the conference hotels. In the nineteenth century filibusters rioted in Lafayette Square to burn the flag of the Spanish consulate after hearing of the defeat of an expedition to wrest Cuba from colonial rule. Filibusters, in fact, launched many of their campaigns against Caribbean and Latin American targets from New Orleans, and in 1847 U.S. troops mustered in the port before sailing for Veracruz during the Mexican-American War. A few blocks from Lafayette Square, where Poydras Street intersects Loyola Avenue, stands the monument to those soldiers who half a century later went to fight on Cuba and Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American War and did not return, but did help turn New Orleans into a major, neo-colonial refiner of Cuban sugar. You could also head in the other direction, toward the river, if interested in the Banana Wharf at the foot of Thalia Street or the Coffee Wharf at the foot of Poydras Street, but you would be disappointed because twentieth-century redevelopment for the Riverwalk Mall, Morial Convention Center, Crescent City Connection bridge, and Cruise Ship Terminal has obliterated the wharves that used to funnel commodities from the tropical Americas into the Crescent City and, from there, up the Mississippi River to the Midwest and beyond. Many Latinos who settled in the city because of the neo-colonial networks associated with bananas, coffee, and sugar initially lived just a few blocks upriver, in the Irish Channel neighborhood, before increasingly joining the “white flight” to suburban neighborhoods that began in the 1960s.

But head back downriver to where Canal Street meets the Mississippi River and you will encounter two prominent memorials of when New Orleans was a city in the Spanish colonial empire during the second half of the eighteenth century. Spanish Plaza, a large fountain built for the city by the Spanish government in 1976 is surrounded by a circular bench backed by the tiled crests of Spain’s provinces, a great spot atop the levee from which to enjoy the vista of the busy shipping of one of the world’s largest ports (Figure 2). On the other side of the World Trade Center, which so prominently marks the foot of Canal Street, another gift to the city from Spain also commemorates the 1776-1976 Bicentennial: an immense equestrian statue of Bernardo de Gálvez, the governor of Spanish “Luisiana” during the Revolutionary War, that celebrates how his troops defeated the British at the battles of Baton Rouge, Natchez, Pensacola, and Mobile.

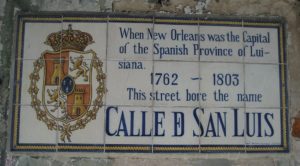

To get a better sense of what the city was like when a colonial capital, before the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, all you need to do is head downriver and cross Canal Street into the Quarter, which comprised the entire city during French and Spanish rule and, in some ways, remains unchanged. At every corner you will see the tiled signs that give the street names during Spanish times (Figure 3). The Plaza de Armas, now Jackson Square, provides the focal point, the river on one side and Saint Louis Cathedral on the other. The two buildings that flank the cathedral remain the most prominent vestiges of Spanish colonial architecture in the city: the arcaded Cabildo, or city hall, retains its Spanish name; the matching Casa Curial, or priests’ residence, has become the French Presbytère. The Mansard roofs added in the nineteenth century might deceive you, but if you imagine the two buildings without them, you might be looking at the colonial cabildo in Buenos Aires or some other city of the former Spanish colonial empire, fronted by an open plaza where troops could be mustered, overlooked by the cathedral and residences of prominent citizens.

The opposite, lakeside margin of the Quarter comprised the outskirts of the city during colonial times but also echoes the city’s lengthy connection to the Hispanic Atlantic. Along Basin Street, a block north of the Quarter in the Iberville neighborhood, Saint Louis Cemetery No. 1 was built in the eighteenth century during Spanish rule, its above-ground tombs similar to many throughout Spain and Latin America. The nearby Congo Square, now a part of Louis Armstrong Park, in the Tremé neighborhood provided a Sunday gathering place for the city’s enslaved residents, among the thousands brought from Africa to Louisiana aboard French and Spanish ships. There, on their day off, they could socialize, plot resistance, sing, and lay the foundations for what would become blues, jazz, and rock-and-roll.

The Garden of the Americas occupies the Basin Street neutral ground, a term that originated when the median of Canal Street formed a neutral strip along the acrimonious frontier between the colonial Creoles who lived in the Quarter and the new, American residents who swarmed into the city after the Purchase and settled mainly upriver from the colonial core. After the Second World War, as part of a campaign to reassert itself as the North American “Gateway to Latin America” in the face of increasing competition from Houston, the city collaborated with local Latino organizations to establish the Garden of the Americas and its three enormous monuments to republican heroes of the Americas: Simón Bolívar for South America, Francisco Morazán for Central America, and Benito Júarez for Mexico (Figure 4).

Heading back toward the river, wander the narrow streets of the Quarter where Júarez and many other Latin American revolutionaries lived while in exile during the nineteenth century, plotting their various coups. In 1853, a young Élisée Reclus, who would become one of the foremost geographers and anarchists of the nineteenth century, also passed through the Quarter. He was headed upcountry to become a tutor to the children of his cousins at their Félicité plantation, about halfway to Baton Rouge along the Mississippi River, but he stopped long enough to observe that New Orleans at that time already had a lot of bars that were always full—some 2500 of them, apparently.[4] After more than two years in Louisiana, the experience of which helped shape his opposition to slavery and capitalism, Reclus left for Central and South America before returning to Paris in 1857 to write his La Terre: Description des Phénomènes de la Vie du Globe.

Not many houses remain from the colonial period due to the conflagrations that periodically swept across the Quarter. Compared to the residences built during French rule in the first half of the eighteenth century, those constructed during the succeeding Spanish period proved more fire resistant due to their stuccoed brick walls and flat roofs, but only a few examples have survived the construction boom of the nineteenth century that replaced almost all the colonial houses with ones built in neo-classical and Victorian styles. One of the few good examples of a typical Spanish house remains at 707 Dumaine Street (Figure 5). Otherwise, various balconies retain some fine examples of Spanish iron work, such as one at the corner of Royal and Conti Streets. Despite the disappearance of residential Spanish architecture over the nineteenth century, though, at least one Mexican sojourner of the time—Justo Sierra, in his 1895 book En Tierra Yankee—felt that New Orleans could still be counted among “those Gulf cities that all seem like sisters, but very large, very developed; Tampico, Veracruz, and Campeche would all fit within it, and it has something of all of them within it, of Veracruz above all.”

Other places of note for connoisseurs of Hispanic and Latino landscapes include the Bourbon Orleans Hotel, on Orleans Street immediately behind Saint Louis Cathedral, which served as the site of the 2017 Conference of Latin American Geographers. The Instrument Men fountain, located near the Dumaine Streetcar Station, depicts a classic jazz band and serves as a reminder that the city’s distinctive musical styles came into being partially through the influences of musicians who visited from Latin American and the Caribbean as well as local musicians who performed there and returned with innovations. As one dramatic example, albeit little known, the Mexican Military Band introduced the saxophone as well as the technique of plucking the bass violin when they played at the 1848 New Orleans World’s Fair.

Although more common in suburban neighborhoods like North Kenner, the Quarter has some Latino restaurants in which to gather to discuss how the city’s diverse roots have resulted in a “cultural gumbo,” to use the local metaphor. El Libre Cuban Café, for example, located near the foot of Dumaine Street, will serve you anything from a Cubano pressed sandwich or a guayaba pastry to a mojito cocktail or a cortadito coffee.

— Andrew Sluyter, executive director, Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers

[1] Once you arrive you will understand why upriver, downriver, riverside, and lakeside have long replaced cardinal directions in the Crescent City, although that sobriquet should already provide something of a clue.

[2] Andrew Sluyter, Case Watkins, James Chaney, and Annie M. Gibson. 2015. Hispanic and Latino New Orleans: Immigration and Identity since the Eighteenth Century. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press (https://lsupress.org/books/detail/hispanic-and-latino-new-orleans).

[3] See this online map of the walking tour associated with this essay (https://drive.google.com/open?id=1XdSWYAujBlYR_SNP5daRkflatGo&usp=sharing).

[4] Fragment d’un voyage à la Nouvelle-Orléans, Le Tour du Monde 1 (1860): 177-92 (https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb311854746).