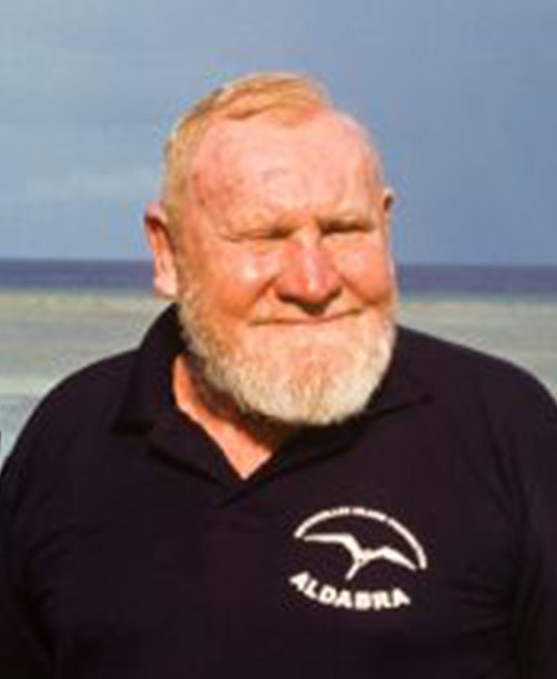

David Stoddart

1937 - 2014

David Stoddart, geographer and one of the world’s leading coral-reef scientists, passed away on November 23, 2014, aged 77, following a long period of declining health.

David Ross Stoddart was born in 1937 in Stockton-on-Tees in the northeast of England. He developed an interest in geography at school. Inspired by the successful ascent of Everest in 1953, he immersed himself in books about the Himalaya and spent two years compiling an atlas of Tibet which included maps showing travel times in yak-days from Lhasa. He also borrowed a copy of William Morris Davis’ The Coral Reef Problem from his local library and was captivated by the illustrations of humid tropical landscapes.

He was the first boy from his school to win a scholarship to Cambridge and went up to St John’s College in 1956 with a determination to be a tropical geographer. For a boy ‘from the provinces’, Cambridge was a whole new world, personally and intellectually, and he threw himself in to his studies. His student vacations were spent on expeditions – to India overland by rail, to Sierra Leone by ship, and to the jungles of Colombia and the headwaters of the Orinoco.

After graduating with a first class degree in 1959 Stoddart had the opportunity to join another Cambridge Expedition, this time to British Honduras (Belize). His task of mapping offshore reefs and islands and interpreting their geomorphology was the beginning of a life-long career charting and documenting the world’s major reef systems in the Caribbean, Pacific and Indian Ocean.

He returned to British Honduras in 1961 for further research into corals and the plants of the cays, working for Louisiana State University before and after a major hurricane, tracking its effects on atolls and reefs. While there, he received a postcard from his mentor at Cambridge, the esteemed coastal geomorphologist Professor Alfred Steers, which read: “My dear David: would you like a job in Cambridge?” David took up the offer and was awarded a PhD from Cambridge in 1964 for his work in British Honduras.

Stoddart was a Demonstrator (1962-1967) and University Lecturer (1967-1988) in the Department of Geography, as well as a Fellow of Churchill College (1966-1987). His research continued on the geomorphology and ecology of tropical islands and reefs, with a particular focus on documenting the plant assemblages present on atolls, making links to evolutionary biology. Several plant species were named for him. He also studied the evolution of atolls since the Pleistocene.

Stoddart’s record of fieldwork was nothing short of astonishing. After Belize, he conducted research in the Maldives, Seychelles, Solomon Islands, at various locations in the Pacific including the Great Barrier Reef, Aitutaki in the Cook Islands, and the disputed Phoenix Islands. Each island study was marked by a detailed field survey of reef topography and biogeography, laying down a Domesday-like benchmark from which future environmental change could be gauged.

Stoddart made his reputation with a campaign to save Aldabra, a large uninhabited raised atoll in the Seychelles. It started during a trip to Addo Atoll in the southern Maldives when he stayed at a military station on the island of Gau. Here, a British RAF officer told him about the studies underway in London to assess the suitability of a number of western Indian Ocean islands for use as military airfields. Having seen from Gau the impact of military development on vulnerable island ecosystems, he approached the Royal Society to suggest an independent assessment of the ecological importance of these islands.

Members of the Royal Society pressured politicians who agreed to attach Stoddart to a Ministry of Defence planning group on Aldabra in 1966, and to a joint US Department of Defence and Royal Naval detachment to Diego Garcia, one of the Chagos Islands, in 1967. On Aldabra he recorded the many endemic plants and animals, mapped the vast colonies of nesting seabirds, and surveyed the habitats of giant tortoises. He concluded that Aldabra was one of the world’s most ecologically important atolls and must not be developed by the military. After lobbying and campaigning in parliament, the government caved in and Aldabra was saved. It became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982, protected as a habitat for unique plants, birds and more than 100,000 giant tortoises. He was last on Aldabra in 2007 to celebrate the 25th anniversary of its designation.

Stoddart was astonishingly productive, writing hundreds of scientific papers on coral atolls, islands and reefs, mangrove swamps and salt marshes. Season after season of field work was meticulously recorded in issues of the Atoll Research Bulletin, a publication of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. He was also the first coordinating editor of the international journal Coral Reefs. He was dedicated to scientific collaboration and support across borders which led him to co-found the International Society for Reef Studies in 1980, serving as its first president, and establish the quadrennial International Coral Reef Symposium.

Stoddart also had an interest in the history of geographic thought, publishing a major book On Geography and Its History in 1986 and writing papers on the influence of Darwin on geographical work. He was also a great advocate for physical geography in the broadest sense and was one of the founders of the journal Progress in Geography.

He grew increasingly restless at Cambridge University in the 1980s. His eccentric lifestyle, long absences in the field, and relaxed attitude to paperwork did not endear him to the university bureaucracy. He also struggled to raise funding for his field research. So when he was offered a position of Professor of Geography at the University of California, Berkeley in 1988 he accepted with alacrity. He served on the faculty until retiring as Emeritus Professor in 2000.

Colleagues note that he was quite a striking figure on campus, with his red hair and red beard contrasting with his “full whites” (white shorts, shirt, socks and plimsolls), worn even in winter. At UC Berkeley his research continued and it went hand-in-hand with his commitment to conservation. He played a central role in the founding of the International Year of the Reef in 1997, and the establishment of the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network. Later years saw a change to studying the role of fringing mangrove forests on island sedimentation.

Sadly, years of exposure to tropical sunshine on his beloved coral reefs eventually took their toll on Stoddart’s health in the form of skin cancer which began in his early 50s. But he obstinately continued his fieldwork on reefs.

Among the professional recognition for his work was the Ness Award (1965) and the Founder’s Gold Medal (1979) from the Royal Geographical Society, the Prix Manley-Bendall from the Institut Oceanographique de Monaco and the Sociéte Oceanographique de Paris (1972), the Livingstone Gold Medal from the Royal Scottish Geographical Society (1981), the Herbert E. Gregory Medal from the Pacific Science Association (1986), the Darwin Medal from the International Society for Reef Studies (first recipient in 1988), and the George Davidson Medal from the American Geographical Society (2001). He was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1979 and a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2000. However, no plaudit gave him greater pleasure than the establishment of a David Stoddart Scholarship by the University of the Seychelles to mark his work on Aldabra.

David was an outstanding advocate for geography within the natural sciences. His wide knowledge of the world’s reefs, plus his broad geographical approach, gave him a unique role in bringing specialists within the natural sciences together. He was at his best as a leader of multidisciplinary and internationally complex international expeditions, but he was also a fine lecturer and inspiring research supervisor, committed to nurturing talent and setting high standards in postgraduate research.

He is survived by his wife, June, son Michael, daughter Aldabra (named after the atoll), and a granddaughter.

Read a comprehensive and entertaining account of David’s life and adventures in his own words