Member Profile: Tim Fullman

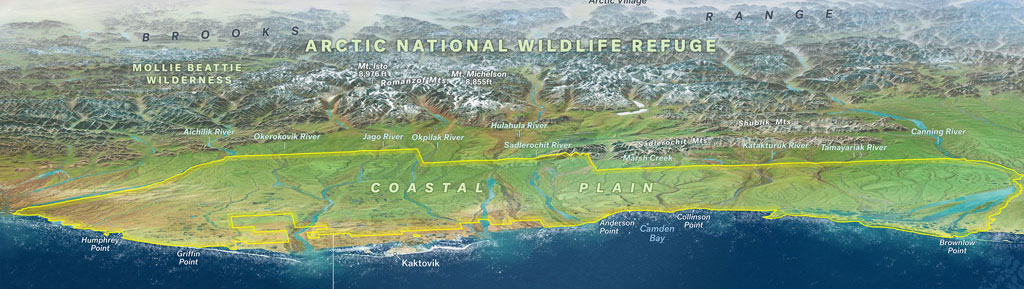

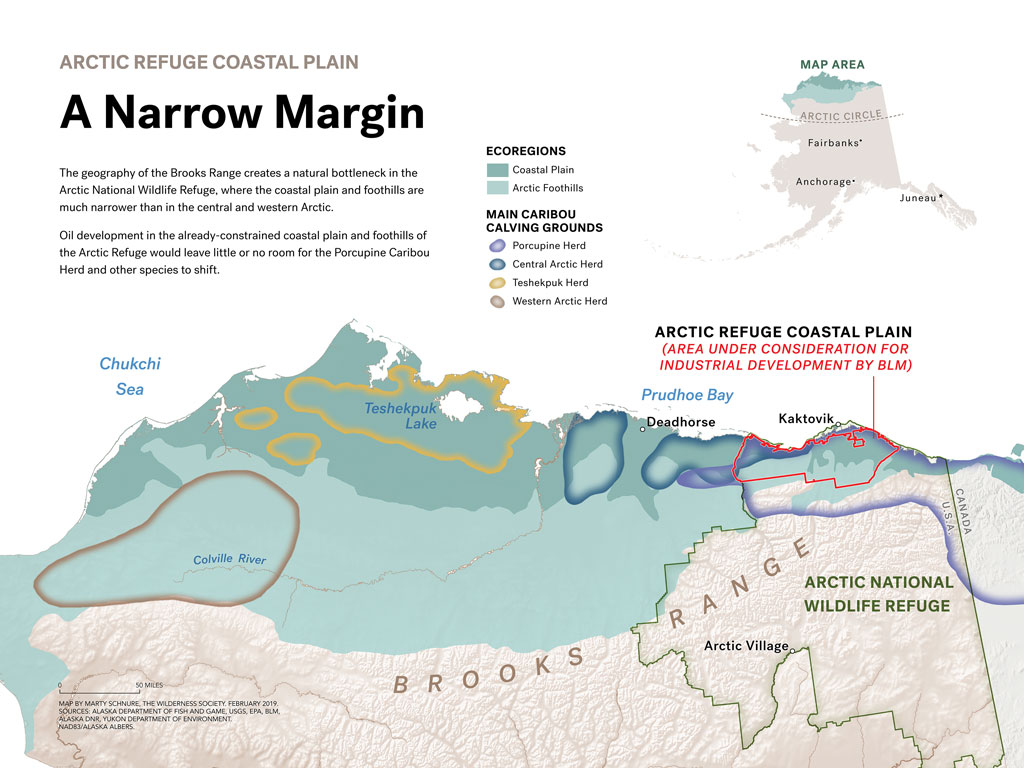

The twice-annual migration of Alaska’s caribou is one of the world’s great journeys. Yet the number of caribou making that trek has been declining for decades due to a variety of factors, including habitat disruption from human activities and a changing environment.

Geographer Tim Fullman, senior ecologist with The Wilderness Society, is one of the people working to understand how to conserve the critical habitat on which caribou rely. Using analyses drawn from spatial and interdisciplinary sources, Fullman tracks and predicts herd patterns as they move over Alaska’s public lands. Much of his research focuses on the Western Arctic Caribou Herd (WACH), among the biggest of the state’s 32 caribou herds.

Geographer Tim Fullman, senior ecologist with The Wilderness Society, is one of the people working to understand how to conserve the critical habitat on which caribou rely. Using analyses drawn from spatial and interdisciplinary sources, Fullman tracks and predicts herd patterns as they move over Alaska’s public lands. Much of his research focuses on the Western Arctic Caribou Herd (WACH), among the biggest of the state’s 32 caribou herds.

Fullman works alongside many partners, from Indigenous community leaders to hunters to tour guides to local, state, and federal wildlife and land professionals. All share a common cause: to preserve the future of Alaska’s caribou in the face of potential impacts from construction projects, energy investments, and climate change. The stakes are high. Alaska’s caribou, once totaling over a million, number 750,000 altogether today. The WACH, alone, has declined by as much as 50 percent since 2004.

In his work, Fullman spends a lot of his time using predictive models, forecasting potential impacts and scenarios that he says are also intimately connected to what we know about now and the past. “To do effective conservation means understanding the past so that we know why things are the way they are now,” he says, “and then using that information now to change the course of the future.”

Geography: The Critical Lens

Starting his career as a wildlife biologist, Fullman discovered that his fieldwork would benefit from an advanced understanding of terrain, place, and migrations. After completing a PhD in geography at the University of Florida, he returned to his work studying large herbivores, this time in Alaska. (Previous research had taken him to southern Africa, where he studied elephants).

Now, he says, his geography expertise takes people by surprise. “In my professional role, I don’t think many people know that I am a geographer, because my title is senior ecologist, and people think of me doing wildlife work,” he says. “Yet I’ve been fascinated as I’ve interacted with more people to come across a number of people with geography backgrounds who are doing work in landscape, ecology, environmental policy, and similar work.”

Why are so many geographers drawn to conservation—or rather, why are many conservationists drawn to geography? “This training seems like it has prepared a number of us to be able to make connections and share, and especially to use maps and other representations to talk about and communicate things in ways that connect with people.”

Geography’s interdisciplinary nature is also a plus: “One of the things that has helped me is that my geography department did not focus a lot on wildlife, but I had colleagues doing human dynamics, economic geography, all sorts of things that fall under the umbrella of geography. I think that prepared me to understand how social science is done, to understand how economics is done, and yet to see the connections where spatial processes and things that happen at space and scale and time influence across all these areas. I think of that as being at the core of geography and what we do.”

Fullman applies ideas and methods from other disciplines to aid in his modeling work. One of these is circuit theory, adapted by ecologists from the world of electronics, which recently helped Fullman and his colleagues model the impacts of road construction on caribou and other species’ habitat. Another tool is the Monte Carlo simulation, used by Fullman and other researchers to test development restriction scenarios for the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPR-A): four from the Bureau of Land Management’s current Integrated Activity Plan, and one put forward by the Western Arctic Caribou Herd Working Group, to which Fullman belongs.

Fullman’s training as a geographer has helped him embrace the many perspectives and complex realities of Alaskan habitats. In studying the ancient presence and fragile present of the caribou, he recognizes the long lineage and millennia-old knowledge held by the Indigenous communities within and around the NPR-A. As he brings new tools to the study of the herds, he embraces opportunities to learn and follow traditional ecological knowledge. “I am very classically trained as a scientist but yet through my time in Alaska, it has stretched my view,” he says. “What does it look like to meaningfully combine and blend all the ways of seeing the caribou?”

“Caribou Tell Us a Little Bit About Ourselves”

Fullman’s work contributes to understanding the pressure on caribou, which is part of a much larger and concerning trend of long-range and major migrations of all species—and humans.

“Caribou tell us a little bit about ourselves. They face some of the same challenges we do: warming climate, increasing development, and changing habitat – but with arctic temperatures increasing at double the rate of the rest of the planet, they’re feeling these challenges first,” says Fullman.

“Are we willing in any place to curb our desire to develop?” he asks “There are some places that are too important and too special.”

Find out more about AAG’s work to address climate change