Born in Manhattan just weeks before the great stock market crash of 1929, Joseph Sonnenfeld, Emeritus Professor of Geography, Texas A&M University, died in Colorado Springs in December 2014, at 85 years of age.

A foundational faculty member of departments of Geography at the University of Delaware and Texas A&M University, he was a pioneer of environmental perception and behavior studies, perhaps most well-known for his work on spatial orientation, sense of place, and Inupiat adaptation to social and environmental change in northern Alaska.

Educated in the New York City Public Schools, Sonnenfeld’s early aspiration was to become a veterinarian; this based on experiences at the Bronx Zoo and at a summer youth camp/ collective farm outside of the City. He undertook an extended, circuitous path towards realizing this goal. In the summer of 1946, with the announced end of the GI Bill weeks away, Sonnenfeld discontinued studies at the Bronx High School of Science, and, at 17 years of age (requiring parental consent), enlisted in the United States Marines Corps, believing military service to be a way he might be able to afford attending college.

Following basic training at Parris Island, South Carolina, in the fall of 1946, Sonnenfeld’s unit was assigned to duty at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. There, requesting a transfer after being bullied by a fellow enlistee, he was given the choice of two overseas assignments: post-war Japan or the Aleutian Islands, part of the Alaskan Territory. He chose the latter, traveling to Adak Island to help protect a United States Navy submarine base, and later to Dutch Harbor, on Amaknak Island. Among his assignments at Dutch Harbor was accompanying an archeologist excavating the site of an early 1800s Russian Orthodox mission. Sonnenfeld was in the Aleutians (also at Kodiak Island) from 1947-49.

While in the Aleutians, he completed the high school equivalency exam, also earning credits towards a college degree. Upon honorable discharge as a corporal from the Marine Corps in 1949, Sonnenfeld enrolled first as a pre-Veterinary Science student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; then transferred to Oregon State College, in Corvallis, to study Fish and Wildlife Science.[1] At Oregon State, it was Geography, however, notably a course in Regional Geography taught by Oliver Heintzelman, which piqued his interest. This led to a Bachelor’s degree (with honors) in Natural Resources, in 1952.[1] Sonnenfeld continued his education at the recently established Isaiah Bowman School of Geography, at Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore. There he studied under economic geographer E. Francis Penrose; climatologist Douglas H. K. Lee; and cultural geographer George F. Carter, a former student of Carl Sauer, Robert Lowie, and Alfred Kroeber at the University of California at Berkeley.[1]

Taking advantage of Hopkins’ strong relationship with the Unites States Navy,[2] Sonnenfeld returned to Alaska in the spring and summer of 1954, under contract from the Office of Naval Research. There, he investigated whether Inupiat who had been working in petroleum exploration for Federal contractors would be able to return to traditional hunting and fishing subsistence activities when testing had been completed. His PhD dissertation, entitled “Changes in Subsistence Among the Barrow Eskimo,” was based on this study and completed in 1957.

Sonnenfeld’s first tenure-track faculty appointment was in the Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Geography, at the University of Delaware, in 1955. In Newark, his departmental colleagues included fellow Hopkins geographer Edward Higbee; sociologists Arnold Feldman, Charles Tilly, and Irwin Goffman; and later, another Hopkins geographer, climatologist John “Russ” Mather.[3] Sonnenfeld returned to Alaska in the fall and winter of 1964-65, this time in cooperation with the Arctic Naval Research Laboratory, in Point Barrow. Geography came into its own as a department at the University of Delaware in 1966, with Russ Mather as chair.[4] [5] Altogether, Sonnenfeld was at Delaware for 13 years.

In 1968, Sonnenfeld rejoined George Carter at an expanding Texas A&M University, in its new College of Geosciences.[6] When a new department in Geography was proposed, various persons were considered for staffing the faculty. According to colleagues, Sonnenfeld was a natural for selection. Although he acknowledged the reality of the natural environment, he insisted that humans ‘discovered’ it through the senses, thus individuals’ decision-making was in relation to a perceived environment. This perceived environment was the one with which humans then made decisions about their own behaviors, with regards to it, hence the creation of a ‘behavioral environment’. Horace R. Byers, A&M’s new dean of geosciences, recognized this immediately, after Carter suggested his name to him. Initially, five faculty were hired to constitute A&M’s Geography department, including also Clarissa Kimber, Ben L. Everitt, and Edwin B. Doran, Jr., who became the department’s first chair. In coming years, they were followed by Kenneth L. White, Robert S. Bednarz, Peter J. Hugill, Campbell W. Pennington, and others.

One of Sonnenfeld’s signal contributions was a 1972 paper on “Geography, Perception, and the Behavioral Environment,” in which he classified the human behavioral environment as consisting of geographical, operational, perceptual, and behavioral elements.[7] Considered innovative, this was required reading in courses in behavioral geography. During the 1980s, he became interested in physiological dimensions of spatial orientation, working across the disciplines with medical researchers and psychologists. He developed a particularly close and stimulating professional relationship with James D. Frost, Jr., MD, a neurologist at the Baylor College of Medicine, in Houston, who had helped develop a portable electroencephalograph machine for the National Aeronautical and Aerospace Agency (NASA).[1] Sonnenfeld was eager to explore the unit’s usefulness in scientific field research.

In 1991, in what he considered a peak achievement, Sonnenfeld received a National Science Foundation grant to return to the far north of Alaska to conduct in-depth interviews on environmental perception, sense of place, and spatial orientation of Inupiat in three villages he had worked in previously, Barrow, Wainwright, and Anaktuvuk Pass, including a few whom he had interviewed in the mid-1950s, forty years earlier. Retiring early from Texas A&M, in 1993, Sonnenfeld moved to Port Angeles, Washington, to continue working on his Alaska study. That effort remained a major focus for over two decades, even after his move to Colorado Springs, in 2006. By the time of his death, the book manuscript, with the working title, “Arctic Wayfinders: Inupiat Travel Behaviors and Travel Environments in Northern Alaska,” had grown to more than twenty chapters; at the time of this writing, it remains unpublished.

At A&M, Sonnenfeld taught courses in Behavioral Geography and Economic Geography. Later, he was asked to engage with students’ increasing awareness of environmental issues and help develop a new undergraduate option with a professional focus on environmental concerns, building on the College’s strengths in the environmental sciences. This became the Environmental Studies Option in Geography, which included foundation courses in Geography together with courses from other departments. He and Kimber team-taught the introductory course for several years as the Option got established.[8] Sonnenfeld’s graduate students at A&M researched topics such as sense of place, environmental perception, and spatial orientation.

Always supportive of human rights, Sonnenfeld recognized early after arriving at A&M that developing a positive environment for the institution’s newly co-educational student body was essential. He worked with others to develop policies and procedures to protect young women from harassment in campus life, including arguing for the establishment of the position of Dean of Women to advocate for women. When that effort failed, he helped establish a path for raising such concerns to the Dean of Students. Sonnenfeld was a frequent advisor on the subject of faculty governance to successive Deans of Faculties, contributing to the establishment of a Faculty Senate at A&M. He served as associate dean of the College of Geosciences, as well in occasional stints as acting department chair.

Sonnenfeld was an active, 50-year member of the Association of American Geographers; a life member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science; and a member, among others, of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology, and the Society for Psychological Anthropology. He was a decades-long member of the Sigma Xi scientific honor society. He was active also in local civic affairs, chairing the Brazos County, Texas, chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union in the early 1970s.

He had a rich, if at times complicated, family life. The son of Jewish immigrants, he and his brother and sister grew up in a Yiddish-speaking, Orthodox household. His father, Rabbi Isaac L. Sonnenfeld, a shochet in a kosher slaughterhouse in New Jersey, had grown up in an Austro-Hungarian Jewish household in Jerusalem, first under the Ottoman Empire, then the British Protectorate. His mother, Mary (Goldhirsh) Sonnenfeld, a piano teacher, had emigrated with her parents from Galicia (today, part of Poland) to Philadelphia. Each day, following classes in the public schools, Sonnenfeld attended Hebrew day school in the afternoon. The Marine Corps was a major change from social world that he grew up in.

Sonnenfeld was married four times: twice to Valerie Wilmot (once in a civil marriage, and again in a religious ceremony officiated by his father), a Canadian biochemist whom he met at Oregon State; once to Carol Price, a graduate student in sociology he had met at Delaware; and lastly, to Liana Bisiani, an accountant and immigrant from Paris and Trieste, whom he met through friends at Texas A&M – their marriage endured more than thirty years, until his death.

As a youth, Sonnenfeld enjoyed singing in a choir, and playing stick-ball in the street. He was a competitive marksman in the Marines. In after-hours at Delaware, he frequented the paddleball courts with colleagues from across the campus. A son of the nation’s largest metropolis, the natural world held a special place in his heart. As a young man, nowhere had he perhaps felt so alone as overnight by himself in a hunting cabin on an Aleutian island. In Delaware and again in Texas he found solace in owning, maintaining, and traipsing on small wooded properties. He delighted, as well, in recreational and productive summer family retreats: in his Delaware days, to the Gatineau River, Quebec; Rehoboth Beach, Delaware; and Acadia National Park, Maine; later, from College Station, to the highlands of Durango, Mexico; the Oregon coast; and the town of Petersburg, on the Alaskan panhandle. In retirement, there was nothing better than walks in the lush, moist rainforest of the Olympic National Park, in Washington state; or among the striking, red sandstone megaliths of the ‘Garden of the Gods’, in Colorado Springs. In his final years, he especially took pleasure in gazing at the towering, snowy Pikes Peak, from the deck of his home.

He is survived by three sons (with Valerie Wilmot), David A. Sonnenfeld, a sociologist; Michael J. Sonnenfeld, lawyer and finance sector executive; and William E. Sonnenfeld, an Aggie forester and forest industry analyst; their wives, and nine grandchildren. And by his wife, Liana Sonnenfeld; and her children by a prior marriage, Kristin (Robbins) Cruz, an architect; and Söndra (Robbins) Rymer, a professional photographer and illustrator; and their respective families.

Selected Bibliography [9]

Sonnenfeld, Joseph. 1957. “Changes in Subsistence Among the Barrow Eskimo.” Ph.D. dissertation, Geography, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, 561 pp.

Sonnenfeld, Joseph. 1960. “Changes in Eskimo Hunting Technology, an Introduction to Implement Geography,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 50(2): 172-186.

Sonnenfeld, Joseph. 1966. “Variable Values in Space and Landscape: An Inquiry into the Nature of Environmental Necessity,” Journal of Social Issues 22(4): 71-82.

Sonnenfeld, Joseph. 1967. “Environmental Perception and Adaptation Level in the Arctic.” In Environmental Perception and Behavior, ed. David Lowenthal. Research Paper No. 109. University of Chicago.

Sonnenfeld, Joseph. 1969. “Equivalence and Distortion of the Perceptual Environment,” Environment and Behavior 1(1): 83-99.

Sonnenfeld, Joseph. 1969. “Personality and Behavior in Environment,” Proceedings of the Association of American Geographers 1: 136-140.

Sonnenfeld, Joseph. 1972. “Geography, Perception, and the Behavioral Environment.” Pp. 244-251 in Man, Space, and Environment: Concepts in Contemporary Human Geography, eds. P.W. English and R.C. Mayfield. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sonnenfeld, Joseph. 1982. “Egocentric Perspectives on Geographic Orientation,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 72(1): 68-76.

Sonnenfeld, Joseph. 1994. “Way-Keeping, Way-Finding, and Way-Losing: Disorientation in a Complex Environment.” Pp. 374-386 in Re-reading Cultural Geography, eds. Kenneth E. Foote, Peter J. Hugill, Kent Mathewson, and Jonathan M. Smith. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Sonnenfeld, Joseph. 2002. “Social Dimensions of Geographic Disorientation in Arctic Alaska,” Études/ Inuit/ Studies 26(2): 157-173.

Notes

[1] Interview by Maynard Weston Dow, Geographers on Film: Joseph Sonnenfeld, San Francisco, California, March 1994.

[2] See Neil Smith, American Empire: Roosevelt’s Geographer and the Prelude to Globalization. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003, p. 264.

[3] Tilly went on to teach sociology and history at Michigan and Columbia, later becoming President of the American Sociological Association. Mather taught at Delaware for 39 years, serving as President of the Association of American Geographers in 1991.

[6] Petroleum again played a role in Sonnenfeld’s academic fortunes. Texas’ Permanent University Fund, derived in part from oil revenue, was quite flush at the time and was used to finance major expansion of higher education across the state. See Vivian Elizabeth Smyrl, “Permanent University Fund,” Handbook of Texas Online. Denton, TX: Texas State Historical Association, 2010. Available: https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/khp02.

[7] Joseph Sonnenfeld, “Geography, Perception, and the Behavioral Environment.” Pp. 244-251 in Man, Space and Environment, eds. P.W. English and R.C. Mayfield. New York: Oxford University Press, 1972.

Written by David A. Sonnenfeld ([email protected]), with contributions from Clarissa Kimber, Professor Emerita, Texas A&M University; and Chang-Yi David Chang, Professor Emeritus, National Taiwan University. Thanks also to David Lowenthal, Professor Emeritus, University College London; David Cairns, Professor and Chair, Texas A&M University; Karen Riedel, Texas A&M University; David Coronado and Jenny Lunn, AAG; and Geoff Somnitz, Oregon State University Library.

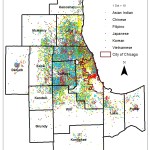

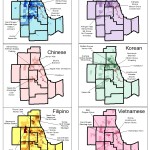

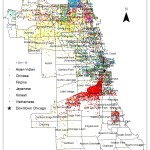

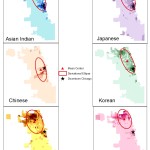

The Association of American Geographers (AAG) will be holding its next annual meeting April 21-25, 2015, in the American business hub city of Chicago, which can be reached by a direct flight from Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and many other major Asian cities. It is little wonder that many Asian cultures feel at home here in America’s heartland global city. On December 19 2014, the “25th U.S. – China Joint Commission on Commerce and Trade” concluded in Chicago. The Chicago Tribune reported that Beijing economic development official Cheng Yuhua expected a dingy industrial city, but the real Chicago surprised her: “What I’ve seen here – it completely changed my mind, the city looks young, it’s full of energy (Chicago Tribune, 21 December 2014).” Although the meeting was focused on U.S. trade, local Chicago got a fair bump in marketing itself as a global city open to foreign investment.

The Association of American Geographers (AAG) will be holding its next annual meeting April 21-25, 2015, in the American business hub city of Chicago, which can be reached by a direct flight from Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and many other major Asian cities. It is little wonder that many Asian cultures feel at home here in America’s heartland global city. On December 19 2014, the “25th U.S. – China Joint Commission on Commerce and Trade” concluded in Chicago. The Chicago Tribune reported that Beijing economic development official Cheng Yuhua expected a dingy industrial city, but the real Chicago surprised her: “What I’ve seen here – it completely changed my mind, the city looks young, it’s full of energy (Chicago Tribune, 21 December 2014).” Although the meeting was focused on U.S. trade, local Chicago got a fair bump in marketing itself as a global city open to foreign investment.