Ethical Research in the Age of COVID-19: A Participatory Forum

Introduction

AAG assembled the following perspectives from the discussions during the AAG Participatory Forum on New Requirements for Ethical Geographic Science in Rapid Research held October 1st, 2020.

AAG assembled the following perspectives from the discussions during the AAG Participatory Forum on New Requirements for Ethical Geographic Science in Rapid Research held October 1st, 2020.

We worked with AAAS’s Science and Human Rights Coalition to experiment with a format that could help us overcome the lack of face-to-face exchanges and networking. We all miss face-to-face meetings, but these important conversations and collaborations on ethics can not wait!

During the participatory forum, no panel of experts was asked to prepare carefully rehearsed presentations, instead, forum moderators were invited to guide discussions on specific questions among small groups of participants. The format creates more opportunities for exchange among the students, professors, and professional scientists who attend. Moderators continued these discussions during the AAAS Science, Technology and Human Rights Conference 2020, opening these questions to scientific disciplines beyond geography, which increasingly rely on locational information. In this series, moderators are reporting back on the discussion they guided at these virtual venues.

This Participatory Forum extends conversations that started at AAG’s Virtual Annual Meeting, April 6-10, 2020, during public panels of the breaking theme “Geographers Respond to COVID-19.” That series, held during the very first months of the pandemic, raised important, high-stakes questions of ethics and human rights, which were documented in a written summer series on the event.

These efforts have been supported in part by the AAAS Science and Human Rights Coalition, of which the AAG is a founding member.

Lessons from the Pandemic: How Can We Put People First in Emergent Research?

Andrew Curley, Sara Koopman, Libby Lunstrum, Diana Ojeda, Lisa Schamess

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised profound questions of research ethics within geography. One of the most vexing is how to foster genuine research partnerships beyond mere participation so that people impacted by the phenomena under investigation are truly part of the conversation and of the search for solutions.

Hurdles for building respectful, collaborative research begin with the structure and intent of many funding opportunities, with their short deadlines and focus on quickly understanding and addressing COVID-19. While we share in the sense of urgency in needing to gain insight and develop solutions to address this public health crisis, the intensity of timelines and expectations for quick turnarounds can hamper meaningful collaboration and even harm longstanding relationships that are often built on trust and follow a slower pace more conducive to genuine relationship building. This context of urgency is also conducive to extractive, colonial modes of top-down “in-and-out” research that devalue input from the communities the research seeks to understand, aside from what can be most expediently gained. The resulting research produces rather than coproduces understanding and, because of this, leads to questionable findings. This becomes even more ethically vexing when there is an implicit or explicit connection to profit or when communities are primarily viewed as “test populations,” as when pharmaceutical companies partner with university researchers in the search for a cure to COVID-19.

COVID-19 has also opened new modes of engagement with research partners, as many of us have been forced to conduct “fieldwork” like interviews, focus groups, surveys, and workshops over Zoom and other online platforms. This shift to online research raises profound ethical questions that begin with difficulties of gaining consent. In many cultural contexts, genuine consent requires in-person conversation and relationship building. Other ethical minefields of online research platforms include the ability of the researcher to record meetings without participants’ knowledge, the ease of hacking platforms like Zoom, possibilities for state surveillance, related difficulties of maintaining anonymity, and broader questions concerning the cultural appropriateness of these more distant forms of encounter that extend beyond issues of consent. In addition, if engagement goes online, this can once again lead to top-down forms of engagement where community or other leaders represent the interests of others who may not have adequate internet bandwidth or cellphone data. This leads to ethical concerns around representation, including whether more vulnerable people impacted by COVID-19 are part of the conversation on how best to address it. In short, use of online technologies to replace in-person encounters requires even more stringent attention to power relationships and ethical responsibilities on behalf of the researcher.

Benefits of the New Normal, and a New Role for Researchers

Despite these concerns, the use of online research tools also offers important opportunities. In addition to allowing us to stay in contact with research partners and even forge new relationships in the context of a pandemic, these tools allow for networking, relationship building, and research in ways that have a smaller carbon footprint, lessening our contribution to climate change. New technologies may also make it possible to forge partnerships in a context of scarce research funding. In addition, we must recognize that meeting digitally can save lives. Universities are prime sites of virus transmission, and hence meeting digitally, even when our partners are local, protects our research partners by preventing virus transmission.

COVID-19 demands new obligations of researchers, given our privileged roles in universities and other institutions of knowledge production. We are in a position to call out interventions that have happened too quickly with little regard for groups that will be most impacted. We see this, for instance, in hastily implemented, overly harsh COVID-19 restrictions that target already vulnerable and exploited groups. These range from militarized restrictions targeting racialized urban residents seen as “prime vectors” spreading the virus, to interventions into the lives of rural communities involved in the wildlife trade whose practices are seen as creating new pathways for zoonotic disease emergence. As researchers and advocates, we have an urgent ethical responsibility to call out inequitable practices authorized by crisis narratives and related dynamics.

Notwithstanding the devastation COVID-19 has brought, the pandemic provides an opportunity to pause in the face of the fast-paced research environment that characterizes an increasingly competitive and neoliberal university. As a welcome response, many universities have added time to tenure clocks to protect pre-tenure faculty. But more can be done. The pandemic provides an opportunity to welcome a slower pace of relationship-building, research, and publication, reinforcing the insights of the “slow scholarship movement,” and returning to core values of what motivates ethical research and the relationships upon which it is built. Slowing down also allows for recognition of the gendered and racialized impact of the virus on us as researchers and teachers, especially as women and racialized groups are responsible for a disproportionate amount of family and community care. In addition, slowing down enables researcher self-care and focus on our mental health, as we are not just researchers but partners, caregivers for our children and elders, and members of our own communities. This points to an additional danger of digital research technologies, in that they may convey a sense that “business as usual” can proceed, when the pandemic provides a needed opportunity to reflect on how unsustainable aspects of pre-COVID work were in the first place.

More than Just a Face: Human subjects in a Time of Geospatial Tracking and Recognition

Junghwan Kim (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)*

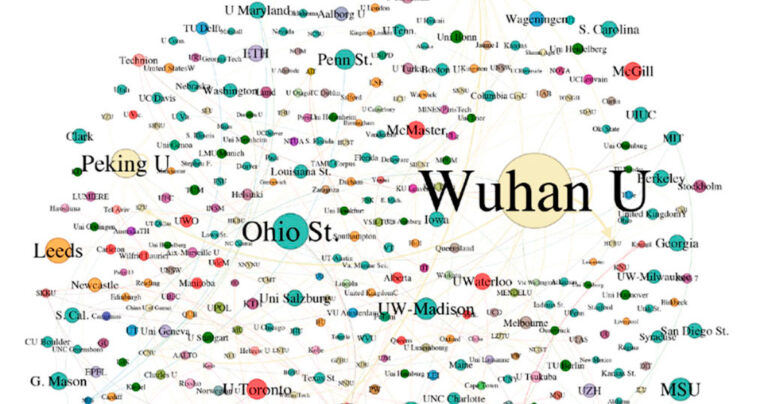

GIScience methods and technologies now enable researchers to collect and analyze highly detailed location information of human subjects (e.g., daily GPS trajectories). Our discussion acknowledged that, along with the benefits of using these new technologies, comes the potential threat of violating geoprivacy. This raises new ethical issues, especially when more invasive new technologies, such as drones, automated location tracking tools, and facial recognition tools (with artificial intelligence) are also used for research purposes. For example, to understand people’s emotions in public spaces, researchers may utilize a camera installed in drone and facial recognition technologies to capture people’s emotions revealed in their faces. However, without proper consent from research participants, the collection of data may seriously breach people’s geoprivacy. Since these technologies are new to us, we may need to critically examine and assess the potential risks of geoprivacy violations related to the new technologies.

Moreover, it is especially challenging to protect the geoprivacy of research participants during the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, some countries have adopted COVID-19 mitigation measures that use information about people’s private location (e.g., digital contact tracing). Although these measures may critically violate people’s geoprivacy, less attention has been paid to the protection of geoprivacy in the name of controlling the pandemic. Under these circumstances, it is important to wisely balance public health and geoprivacy protection. In parallel to such concerns in the public policy, researchers are also subject to pressure to overlook the importance of “geoprivacy protection” at a time when more knowledge about COVID-19 is urgently needed. In this light, our group discussed the need for more attention to be paid to protecting privacy while implementing COVID-19 policies and conducting research.

We also agreed that we should continue our conversation in a context similar to the AAG/AAAS online forum, to enhance the awareness of geoprivacy and related important ethical issues, not only in the community of geographers, but also other scientists at large, including IRB personnel. Although geoprivacy is one of the important issues that has been widely studied in the field of geography, the group agrees that there is still a long way to go. For example, some researchers, particularly those outside of the geospatial disciplines, might not even be familiar with the concept of geoprivacy, and might need to be made more aware of the pitfalls. Otherwise, research participant’s privacy might be critically violated through spatial reverse engineering, for instance, even if a map does not explicitly illustrate their specific identity (e.g., name and street). This is particularly important as interdisciplinary research that uses sensitive geospatial information is being widely conducted. Therefore, the group discussed that more efforts are urgently needed to promote the awareness of geoprivacy issues among researchers.

* The moderator greatly appreciates the participants’ invaluable time and input during the discussion.

Safeguarding Confidentiality in GeoSpatial Research

Ranu Basu

How should scholars safeguard confidentiality of human subjects in research, when we know that re-identification of anonymized data is sometimes possible, and when geographic representation (or interpretation) is often flawed?

The concern for protecting human subjects’ confidentiality is especially compelling because of the uneven power relations that are involved in the production of knowledge and its implications for marginalized and displaced communities (i.e. racialized, gendered, forced migrant, indigenous, and precarious labor). These concerns are amplified when handling large data sets, including when researchers use mapping without due consideration to ethical guidelines. The concerns raised in our group included the need to contextualize these guidelines: from the often limited incorporation of the historical or political contexts of communities; recognizing the continuing legacies of colonialism and imperialism including the contested geopolitics of borders and territoriality; to questioning the underlying socio-spatial processes leading to uneven development at all levels. Geospatial technical concerns and confidentiality of data were discussed in relation to these contexts regarding errors in the representation of spatial data; fast-mapping; aggregation techniques (MAUP) and use of suppressed data; the politics of categorization and spatial orderings; power imbalances of conducting research involving vulnerable communities and developing true participatory research. Geographers offer valuable insights and guidelines in approaching such challenges through the integral linkage of critical theory with geographic methods.

A number of questions were raised to facilitate discussion: Whose confidentiality is at stake?; How is confidentiality compromised?; What could be the possible repercussions?; How might geographic representation be flawed?; What challenges has COVID-19 further posed to these issues?; and What perspectives and unique insights can geographers offer? Based on their research in the field and inter-disciplinary insights, the participants discussed the various complexities related to privacy and confidentiality, ethical dilemmas, the technicalities and nuances of geospatial approaches, conducting research online, institutional processes, and various participatory models as ways to avoid reproducing power differentials.

Some highlights during the discussion included:

The ethics of interviewing displaced and non-status migrants, particularly those vulnerable to deportation. It remains important to reduce the risks of re-identification of anonymized data alongside legal status, ethnic tensions, and inequities that surround Indigenous and racialized populations.

The process and uncertainties of acquiring institutional approval during a time of COVID-19, especially with changing realities and resources for ensuring anonymity across the virtual communication platforms we increasingly rely on, and which carry their own risks with regard to confidentiality.

Contradictions unravel between trying to conduct research safely during COVID-19 while at the same time ensuring privacy. While Zoom interactions and video calls have become a central method for holding distanced meetings, there are difficulties in maintaining descriptive information private. Additionally, if translators and transcribers are needed, meetings must be recorded and shared.

Conducting research online can have an impact on subjects’ spatial experiences of their privacy and comfort, which might deter individuals from participating in studies. Accessibility is also a concern, along with the inherent digital divide that already impacts marginalized people’s ability to participate in civic, educational, and economic opportunities, including their ability to participate in potentially beneficial research and to be heard in the results.

Alternative applications and encrypted programs were discussed, to prevent data mining, along with blurring of faces or deletion of names of participants in video calls in efforts to secure anonymity. The reliance on internet and third-party access to data for most programs poses barriers to full anonymity, particularly with regards to who is included and who is left out of the research process.

As data mining becomes more sophisticated, re-identification becomes more likely. Although big data continues to be sought after, the ethics of its applications are not always considered, particularly in the movement of data to online collections. This can put researchers at odds with the institutions that seek out or provide their data, as the institutions seek bigger and better datasets, while the researchers seek to protect their subjects’ privacy and the integrity of their results.

With the wide proliferation of maps, there are also flawed interpretations and representations which consequently create false depictions that in some cases can lead to communities being stigmatized, criminalized, and further excluded. Further, colonial histories related to the mapping of territorial rights, contested borders and occupied spaces often remain unaddressed. The technicalities related to these conundrums were discussed – whether addressing the modifiable area unit problem, errors associated with aggregation of data, the sources of digitized data, missing data.

The focus on volunteer geo-information in applications poses ethical issues: people are not always aware of how their data will be used for other issues. In a time of COVID-19, as data is increasingly being called upon to navigate fast-paced scientific inquiry, the barriers to safeguard data are lower. While many geographers are aware of geo-privacy issues, other researchers, and policy makers, are not. It is therefore important to continue raising these issues in contemporary frameworks and to thoroughly (re)think and rebalance the need for locational data with the need for privacy in an ethical research process.

Geographers can help raise awareness of geo-privacy, not yet a well-known concept. It would be helpful to continue questioning the practices involved in geo-privacy with researchers, provide guidelines for ethics and mapping to institutions, and further these debates in the classroom.

Lastly, geographers might lead toward creating a balanced approach to maintaining anonymized spaces and identities, in the interest of safeguarding confidentiality, while also listening and giving voice to a wide range of perspectives in these spaces.

Who are the human subjects or places in research and, who is benefitting from rapid Geospatial COVID-19 findings?

Sheryl Luzzadder-Beach, on behalf of AAG and AAAS SHR Forum Participants

Participants in this breakout conversation considered the perspective of what insights their disciplines (Geography, Chemistry, Sociology, Statistics, Health Sciences, Science Writing, Physics… etc.) bring to two questions on Geoethics and Rapid COVID-19 Research:

- Who is carrying the burden of rapid Geospatial COVID-19 science (who are the human subjects or places in research); and, who is benefitting from rapid Geospatial COVID-19 findings?

- Who is carrying the burden of COVID-19 Geospatial science (who are the human subjects or places in research)?

The Science and Human Rights Framework (UNHRC Article 15, The Right to Benefit from Science) was an underlying focus to our breakout conversations:

- How science can help Human Rights,

- How science may hinder Human Rights.

- How to help scientists’ Human Rights in these situations.

Discussions with AAG members and with AAAS members highlighted a number of concerns for human subjects and places. First, producers of knowledge bear a burden through the risk of acquiring and transmitting a deadly disease through place-based research. People seeking knowledge, and asking for rights and change can be intimidated by authoritarian regimes, who can use regions to clamp down on protests, or can shut down the voices of scientists attempting to share information. What Geographers bring to the table is the ability to use spatial knowledge to convey the geographic, temporal and intensity distributions of a pandemic, to inform the public. This relies on public health officials who bear the burden of rapid and accurate reporting of results. Risks are run in the human subjects research arena of the need for rapid IRB approvals for research, and care must be taken to protect not only vulnerable individuals, but also vulnerable geographical populations, whether it is at the neighborhood level, or community level, so that they are not discriminated against, and they receive the resources needed (COVID testing, medical care, personal protective equipment). The groups suggested that IRB protocols need to be expanded and updated to consider the urgent global proportion and timeliness of rapid response to a pandemic.

The need for rapid peer review was also seen as a pressure point on publishers and scholars alike, for rapid research and validation of results in this deadly topic. Frontline medical researchers are dependent on other sciences in important ways. For example, the burden of research about the nature of airborne particles and the effectiveness of masks is dependent on research carried out by physicists to test the lingering behavior of aerosols, and how masks do or do not screen this, which is a dimension of research beyond medicine, but complementary and necessary. Science itself has a burden of building trust in a political climate of skepticism, and the politicisation of science. The natural sciences, biosciences, and medical sciences are seen as the first line of bearing the burden of research, a cause for concern among Social Scientists and the Humanities in the competition for funding in the time of COVID-19. However, the Humanities and Social Sciences bear an important burden of providing models of human behavior to assist in understanding the vectors of the spread of COVID, and the differential impacts on communities based on the resources they may or may not have. This is amid fears that the shift in funding for research in general has focussed on the hard sciences and medical sciences, and whether the research is of direct benefit to COVID or not. The public also bears a burden, including opting in for the greater good into COVID notification tracking programs on mobile devices, which link back to COVID geographies. More broadly, Adults bear much of the burden of testing and of clinical trials of vaccines to come. Then, linking COVID data to geographies when you get to smaller neighborhoods encounters the same privacy issues as census data, as discussed above. Do the conversations around reporting geographic data for COVID-19 and for racial and ethnic data overlap? It can link neighborhoods to certain ethnic groups. But also it can show that certain neighborhoods have reduced access to healthcare and other resources. As global citizens, we are all burdened in how we navigate life during COVID-19 and protect the greater society through our own actions and choices.

On the individual level, adults benefit from being able to consent to and participate in trials of COVID-19 testing and vaccines, and consent to the use of tracking devices. Children and other vulnerable populations do not have this benefit. And the question arose, can children even consent to tracking? Children are the last to benefit, and have suffered in so many ways from the politicization of school attendance versus online schooling. On a larger scale, Big business including big Pharma, online businesses, and delivery services have benefitted overall, but as focussed sectors of an otherwise depressed global economy. The ethical concern is how those who benefit move forward and think about the future of research based on how we define the broader impacts of our work, whether in geography or other fields. The medical and pharmaceutical industries who focus on COVID-19, in lieu of other lifesaving research, also stand to benefit in the short term. Beyond academia, the developed world benefits due to a collectively higher standard of living and access to resources, but in the developing world, fellow citizens struggle to earn enough money for lunch each day, making personal sacrifices to earn those wages. The privilege of staying home places big blinders on the everyday effects on other people where earning a livelihood is a daily affair.

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0081