Vote for Geography

No matter what happens with this week’s election, the United States will pivot.

No matter what happens with this week’s election, the United States will pivot.

Four years ago, most people in my life expressed horror, shock, and disgust following the presidential election in the United States. The day after the election, I shared with my husband my apprehensive relief following the results. I’ll explain.

I grew-up in Atlanta. Looking back, it seems that I may never again live in a place with such diversity. I spent my primary, secondary, and post-secondary school life living in a world of open sexism and racism. Then I moved, first to East Lansing, Michigan and then to Eugene, Oregon. My children mostly grew-up in Eugene. While beautiful, I often say that my biggest parenting regret has been raising my children in a loaf of Wonder Bread—white, white, white—slice after homogeneous slice.

I realized that once out of the south, sexism and racism still exist. They’re just packaged differently. Their insidiousness is delivered with smiles and well-meaning comments. I have had different versions of this conversation many times:

Person: “Oh, you’re from the south. They’re so racist down there.”

Amy: “Yes. But, there’s racism here too.”

Person (a counter argument, usually centered around a sentiment like): “How can we be racist when there aren’t many Black people here” or, “I am color blind in my beliefs.”

How indeed can we participate in “-isms” if our gut, our heart tells us we are not that way? Remember Stephen Colbert’s “truthiness”? Try googling it if you do not.

That’s when I realized that the most sneaky and powerful form of racism…the one that perpetuates it…is the one that refuses to be acknowledged: the denied racism.

I’ve heard some people argue that the reason behind denied racism, denied sexism, denied ableism, and denied other-isms is as simple as not having the lived experience. Maybe Harper Lee sums it up well: “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view.” (Atticus to Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird).

My proposition for the real reason behind denied bias is less merciful. The denial of racism, just like the denial of sexism, ableism, and any other “-ism” is what gives those biases their core strength. We know that denial is not merely human nature. In fact, the human brain uses denial as a way of helping us process difficult truths, such as when we experience a traumatic event. We are literally programmed to use denial as a tool to protect ourselves from the reality that is happening in our lives.

Denial of existing biases is about identity. Denial allows us to look away from reality and see what we need to see. We use denial so that we don’t feel bad about our own identify, our self-respect, our global understanding, and our society. Confronting such deeply-entrenched denial requires something extraordinarily powerful to happen.

So, thinking that the election results may be the extraordinarily powerful event to wake people from their denied-bias slumber, I experienced apprehensive relief following the 2016 election. Relief because the election would reveal, finally, how broadly and deeply rooted many forms of bias are in America. Apprehensive because pulling off that big ugly bandage would uncover a festering and extremely painful wound.

Four years later, it is now critical to ensure that another denial doesn’t take hold—the denial of root causes and our responsibility.

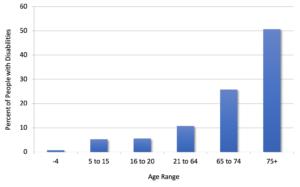

There are so many specific events over the past four years for which we can be angry with current leadership: hideous comments about women, refusal to condemn white supremacy, overtly racist practices, publicly mocking people with disabilities…there have been so many atrocious acts these past four years that it’s impossible to provide a complete list. But…

I believe that anger at leadership for causing these rifts is largely misplaced. Our current leadership did not create the painful wounds of bias: racism, sexism, ableism…fill-in-the-blank-ism. Rather, our current leadership simply reflects America’s long-standing EverythingOtherThanAbleBodiedWhiteMale-ism. Leadership merely gives voice to a widely accepted set of beliefs based in collective biases.

It is those shared biases that deserve our introspection and disgust.

In moving forward, the emotional healing process includes four to seven stages, depending on whom you ask. Regardless of the source, stages present in a sequence similar to this: 1) Denial, 2) Anger/Expression, 3) Reflection, 4) Transformation, and 5) Corrective Experiences.

Our current leadership has been very effective in starting the process to move us out of Stage 1 and into Stage 2. And, now his work is done. We need a new form of leadership to continue. The next Stages are harder. We held on to and denied our biases for too long to think that they will magically transform to Corrective Experiences. For those difficult Stages, we need leadership that demonstrates decency, maturity, integrity, grace, strength, and empathy.

We need leadership who understands that we cannot stay in the Stage of Anger/Expression without causing new wounds. We also need leadership that understands interconnectedness of social foundations, and that moving toward Corrective Experiences has to happen through strong societal infrastructure.

But that is not all. Just as compelling (especially for geography) is the need to vote for science. In the past four years, science has experienced a marked uptick in interference, contempt, dismantling of research data, personal attacks, and an overall assault on validity of scientific research from our leadership. Much of the American public has followed.

Now, read that paragraph once more and substitute “education” for “science.”

Again, leaders don’t create EverythingOtherThanAbleBodiedWhiteMale-ism. Rather it’s the persistent existence of -isms that creates leaders who mirror those biases. Voters choose leaders who best represent their beliefs. In response to outcries of racism- and sexism-motivated voting in the last election, how often did you hear angry, defensive words such as “I voted for leadership because of x,y,z policy. I don’t support their sexist, racist, ableist views.”

Bullshit.

Acceptance of sexism IS sexism. Acceptance of racism IS racism. Acceptance of ableism IS ableism. And…voting for a sexist is sexism. Voting for a racist is racism. Voting for an ableist is ableism.

So, regardless of the outcome of this election, we will pivot—backward or forward.

The bandage has already been yanked off. We don’t need to go back.

I plan to…Vote for science. Vote for education. Vote for decency, empathy, grace and intelligence. Vote for geography.

—Amy Lobben

AAG President and Professor at University of Oregon

lobben [at] uoregon [dot] edu

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0080

Please note: The ideas expressed in the AAG President’s column are not necessarily the views of the AAG as a whole. This column is traditionally a space in which the president may talk about their views or focus during their tenure as president of AAG, or spotlight their areas of professional work. Please feel free to email the president directly at lobben [at] uoregon [dot] edu to enable a constructive discussion.

Last month I shared

Last month I shared

Geography has always been about data. After all, the field was founded and developed over the search for more and better information. It was 200 years ago that

Geography has always been about data. After all, the field was founded and developed over the search for more and better information. It was 200 years ago that

It does not seem so long ago that people were talking about the compression of space and time, about the “ends of

It does not seem so long ago that people were talking about the compression of space and time, about the “ends of

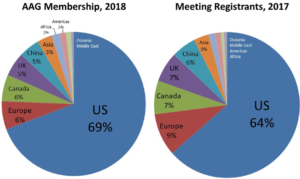

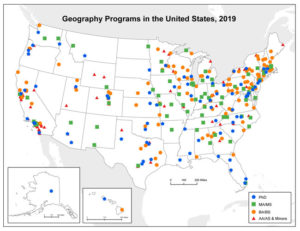

Professors lucky enough to obtain full-time employment find themselves in a variety of job environments and at different types of institutions with varied research expectations, teaching loads, and opportunity to mentor graduate students. Some geographers stand alone in a department with other faculty; other geographers are part of a large unit with 20 or more faculty and an opportunity to specialize in their specific subfield.

Professors lucky enough to obtain full-time employment find themselves in a variety of job environments and at different types of institutions with varied research expectations, teaching loads, and opportunity to mentor graduate students. Some geographers stand alone in a department with other faculty; other geographers are part of a large unit with 20 or more faculty and an opportunity to specialize in their specific subfield.