On the Map: Where Were You When?

By Allison Rivera

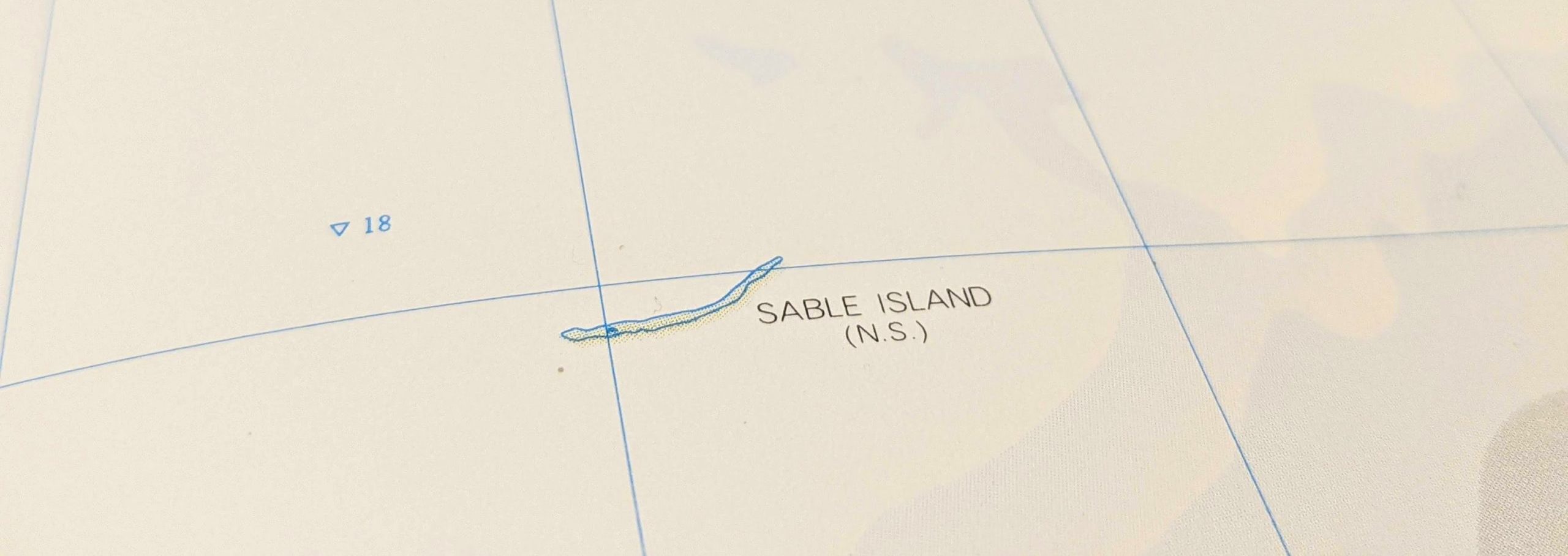

It is no secret that the Earth has drastically changed throughout history, though it can be hard to capture evidence of its evolution. Thanks to the innovative work of software engineer Ian Webster, you can explore Earth’s transformations in real time. Webster created an interactive “Ancient Earth” experience using the revolutionary work of palaeogeographer Christopher Scotese.

I always wanted to build a time machine. These maps allow me to travel back through time.

—Christopher Scotese

Scotese’s love and inspirations for paleogeography began during his childhood, when he would dream of traveling back in time. He recalls his ambitions from a young age: “I have had an interest in Earth History since childhood. During my summer vacations (age 8-10), I started a journal entitled A Review of Earth History by Eras and Periods. I always wanted to build a time machine. These maps allow me to ‘travel back through time.’”

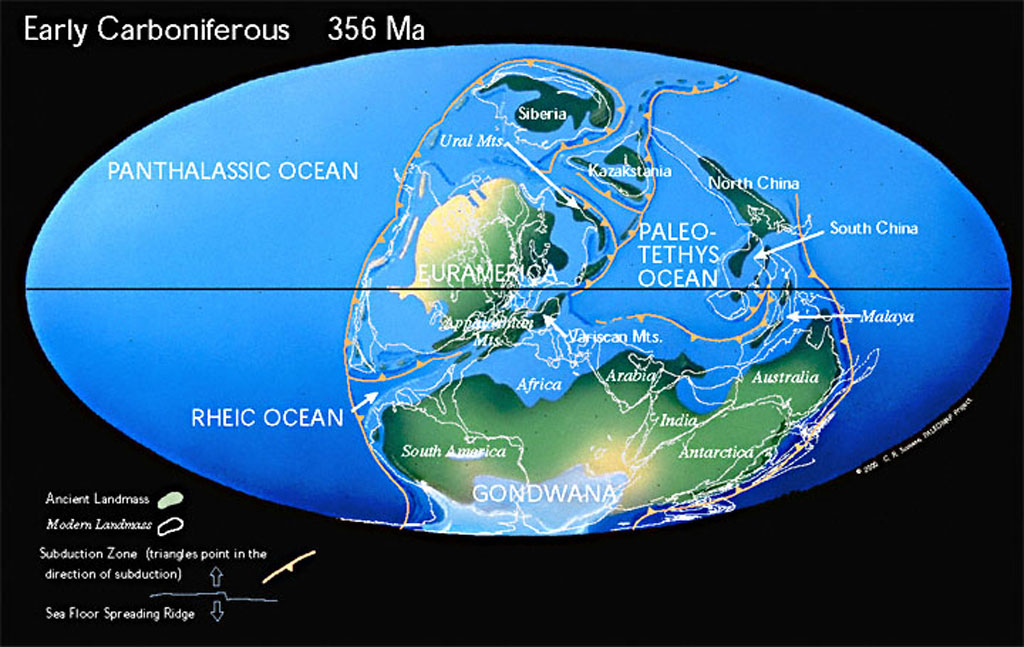

It was from these ideas that his Atlas project was born. The Paleogeographic Atlas project began during his undergraduate career at the University of Illinois (Chicago). It was first published as what could be described as “flip books,” with some computer animations. It was not until his graduate career when the Atlas was updated to include principal scientific areas such as plate tectonics, paleomagnetism, and paleogeography. Despite other paleogeographic maps having been published at the time, these maps were noteworthy. The Atlas Project was the first to illustrate plate tectonics and paleogeographic evolution of the Earth. Scotese was also the first person to write software to animate the history of plate motions. However, he did face some challenges along the way. He noted that the greatest obstacle of the project was that “It takes a long time to accumulate the knowledge and experience to tell this story.” He is now writing a book titled The History of the Earth System, allowing him to compile the mass of information he has accrued over the years. Scotese also knew that updating the maps was no easy feat, and, with the help of many colleagues, has continued to integrate new and improved scientific ideas into the Atlas.

Scotese made sure to take many ideas into account from various scientists. Having worked with paleoclimatologist Judy Parish to incorporate paleoclimatic interpretations in the reconstructions of the Earth, he was able to develop a parametric climate model. Furthermore, Scotese used linear magnetic anomaly data and satellite imagery to create a model for Mesozoic and Cenozoic plate and ocean basin reconstruction. While his work paved the way for the current knowledge and understanding of time periods such as the Mesozoic and Cenozoic, those such as the Paleozoic remain unknown. Here, the map is based on information and results presented in a symposium on Paleozoic Paleogeography. The oldest map of the Atlas was the last to be assembled, but is based on a model Proterozoic plate tectonics, developed by Scotese and other geographers. From this, they were able to conclude that the Proterozoic was a time of Rodinia supercontinent assembly and breakup. Each map incorporates some form of scientific data and knowledge, making it as accurate as possible.

Despite the amount of collaboration, research, and time that went into this groundbreaking project, Scotese describes it as ongoing. The Atlas only describes the current knowledge and understanding of ancient Earth. As with any science project, new data and findings are always emerging, which leads to the need for constant updates and improvements to the Atlas. To keep up with new information, Scotese has a vision for a digital Atlas. Combining scientific data with technology such as GIS will allow for not only improved user friendliness but also easier compilation of data. Programs such as Paleo-GIS will be the foundation for the next version of the Atlas. In addition, Scotese is working with a group of scientists to add other Earth System information such paleoclimate, paleoenvironmental, biogeographic, and palaeoceanographic information.

Even though Webster’s project is based on the old version of the Atlas, it still has many features that make it easy to understand and educational. His work gives people living in today’s world a sense of connectedness to the ancient earth through time.

View Christopher Scoteses’s website Explore Ian Webster’s visualization of Dr. Scotese’s work

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0134