Welcoming a New President to AAG – Interview with Patricia Ehrkamp

For the last president’s column of her term, President Rebecca Lave talked with incoming President Patricia Ehrkamp about her experiences within the discipline and her aspirations for her upcoming leadership at AAG. The following conversation offers insight into the new directions for the 2024-25 presidency.

For the last president’s column of her term, President Rebecca Lave talked with incoming President Patricia Ehrkamp about her experiences within the discipline and her aspirations for her upcoming leadership at AAG. The following conversation offers insight into the new directions for the 2024-25 presidency.

RL: What brought you to geography?

PE: I’ve been a geographer since fifth grade. I grew up in Germany, and geography is taught in school and for a long time it was my favorite topic. Probably what drew me to geography then, and keeps me here, is that it’s a way of thinking about the world and understanding the world around us. And that’s fascinating.

RL: Yes, I love the way that geography so deeply connects theory with fieldwork: if you want to understand a place, you need to go there and engage in a deeply empirical way.

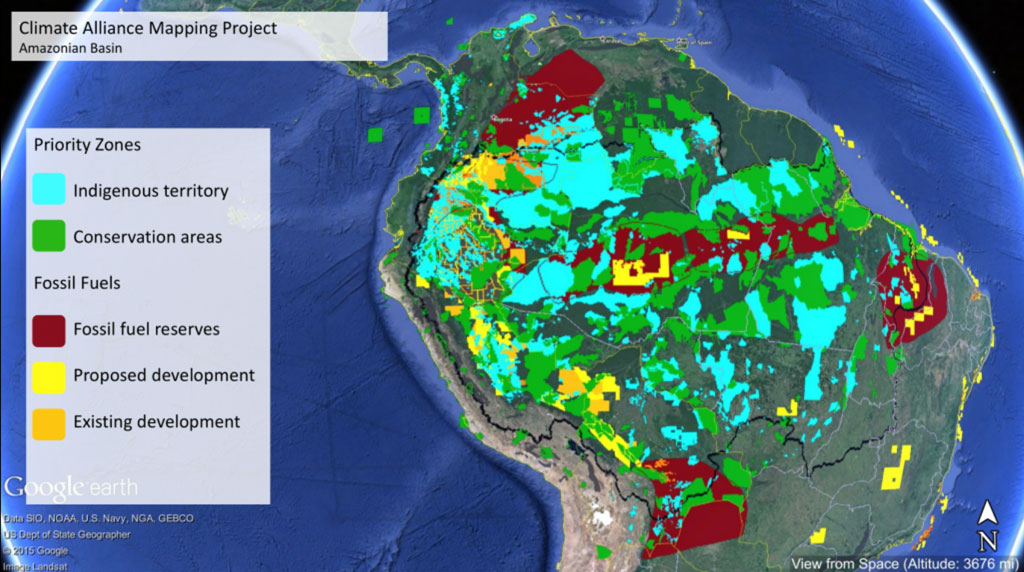

PE: I love the integrative nature of geography; we can study physical geography, study drought and desertification (which I did quite a bit of in Germany) alongside immigration and geopolitics, which is what I specialize in at this point. All of it in so many ways are about the relationships, and connections between environments and people, and people and environments, and different places. The fact that we, as a discipline, can even think of tackling such complex questions as climate justice, human displacement, and food security, that’s what continues to excite me about geography

RL: What do you tell students about what makes geography so relevant to the questions of the day?

PE: It’s such an amazing discipline, you know. There are so many ways that geographers can make a difference: think about making cities more livable and more just for more people. We study climate change, from both the physical science perspective and considering its impacts on people’s lives, and hopefully find solutions to alleviate these impacts. That’s what makes geography so unique and so relevant. We can analyze and map data, and then put that data to work in the interest of social justice.

RL: What prompted you to run for office in the AAG?

PE: I’ve been involved in the AAG for quite some time. I’ve served on the boards of a number of different Specialty Groups, and I’ve always enjoyed them, it’s always been a great experience. I had no idea that I was going to be nominated as vice president—as it so often happens, I think. But in thinking about it, it’s an important time to be involved, right? We’re looking at changes in higher education, challenges to academic freedom, and it’s especially important, if we have expertise and energy that we can lend, that we do so. And there are things that I want to do, also. Like thinking about how to make a more inclusive discipline: there are important efforts on the way with the JEDI Committee and Risha RaQuelle’s leadership. There is important work to support, like your work on the Public and Engaged Scholarship Task Force. So, I thought I could maybe help the broader project of working toward positive change and making a more equitable discipline of geography. That’s really what made me run.

RL: What would you say to a member considering volunteering or serving in some way with AAG?

PE: Do it! Get involved. I’ve learned so much from serving on boards of Specialty Groups, and it’s been such a joy also. You make all these connections with people from across the country, from across the world, even. One of the things I did on one of the boards was read submissions for student paper awards. You get to see this fascinating work people do, the next generation of geographers with all their brilliant ideas. So, what’s not to love? I would encourage anybody who is interested in participating to get involved. It really gives you a whole different perspective on the discipline, the organization, and it allows you to work with others and collaborate on the things that matter.

RL: I would totally agree with you on all of that. I had a somewhat different path because while I did a bit of Specially Group work, my main involvement with AAG was through the Honors Committee. Celebrating people for their work is my happy place, and it was super interesting to see the process and get to learn more about the work of the people that were nominated. Also, the committees all have people that I never would have run into otherwise because they’re in different geographic specialties. That was really cool, too.

PE: I agree, working with geographers across the breadth of the discipline is fabulous! All the committees do really important and interesting work on behalf of geographers, and it is so rewarding.

RL: What initiatives and projects are you most excited about for your time as president?

PE: One of the big reasons why I wanted to run is my interest in strengthening approaches to mentoring. In my home department at the University of Kentucky, we’ve done a reasonably good job of creating support structures. When I was chair, I worked on creating policies, best practices. One of our most important jobs as geographers is to train the next generations and make sure that they have the best possible situation when they’re starting out in their careers. It’s not the same for everybody because some of us will end up in very small departments, in different types of institutions, or even being the only geographer at their institution. One of the things I wanted to do is think about how the AAG can best support earlier career geographers. What structures we could put in place. The Mentoring Task Force has been looking at what best practices exist, and how we can put them together. We are having conversations about topics like, how do you know when you want to be a mentor, how do you become a mentor and, if you’re becoming a mentor, are there ways that you can be trained? Are there models that work better for smaller or larger group settings so we don’t just rely on individual one-on-one mentoring?

RL: Those feel like such important questions to me. I also love the focus on moving beyond individual mentoring because I think having a broad range of mentors for a lot of different things is super helpful.

PE: Yes, you need an ecosystem, right? I’ve thoroughly enjoyed mentoring, too, and I think about getting more people involved as mentors. There’s so much learning to be done on both ends.

RL: Is there anything else that you would like to add?

PE: I so enjoyed the Honolulu meeting and the way the AAG– thanks to you and everybody at AAG and local collaborators who worked so hard–had a meeting that was so well prepared, where you felt grounded, where you had an idea of where you were going and why it matters how you show up as a geographer in a place. I think that was brilliant, and the meeting was just such a wonderful experience. I loved learning from all the plenaries on Indigenous work or scholarship, and questions of extraction and coloniality and again related to questions of justice. I am excited to carry that forward into the next meeting in Detroit, and I hope everybody else is going to be inspired to work with us on that. I think being grounded in the place, being able to bring the city and the place into the conference, bringing the conference of geographers into the city and surroundings–in meaningful ways, not just drive-by visits–I think that is so important, and we generally do that well as geographers.

And lastly, I’d like to say that I’ve been really enjoying this first year of AAG service. I’ve learned so much as vice president and I’ve very much enjoyed working with the Council and everybody on it and AAG staff, who are so committed and competent. And I know they’re working really, really hard all the time. Not just to create Annual Meeting experiences but to support us year-round, to make sure that there is a voice from the AAG to the outside world as well, which I think is increasingly important. I’ve learned a lot and I look forward to the next couple of years.

Please note: The ideas expressed in the AAG President’s column are not necessarily the views of the AAG as a whole. This column is traditionally a space in which the president may talk about their views or focus during their tenure as president of AAG, or spotlight their areas of professional work. Please feel free to email the president directly at rlave [at] indiana [at] edu to enable a constructive discussion.