Point Reyes National Seashore: A Brief History of a Working Landscape

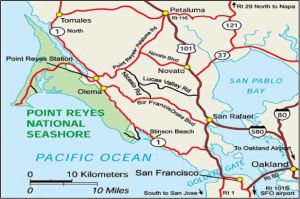

Just a mere forty windy miles north of San Francisco is a popular natural wonder. Point Reyes National Seashore and the Phillip Burton Wilderness Area are prime destinations for visitors near and far. While many visit these places to fulfill their quest to get away from the hustle and bustle of the nearby city life and commune with the natural landscapes, some folks get to call the seashore home. Point Reyes National Seashore is a working landscape, containing dairies and ranches that have been in place for generations. However, with mixed use comes disagreement over the proper use of the space and discussions on the purpose of national park system units.

Long before Point Reyes became a National Seashore and a site for controversy, it was home to the Coast Miwok tribes. Living on the Point Reyes peninsula for centuries, the Coast Miwok found their lives uprooted when they were relocated to nearby Missions in the late 1700s to early 1800s (DeRooy and Livingston 2008). After the Coast Miwoks’ expulsion, Mexican rancheros grazed cattle on the land during the 1830s. When California became part of the United States in 1850, the land was divided by the owners into 32 tenant-run diaries and cattle ranches to keep up with the demand from the urban centers of the San Francisco Bay (Watt 2002; Deur and Mark 2011). World War II even brought mining and military installations to this future “untrammeled” wilderness area.A great deal of the current contention lies around the fundamental issue of working landscapes as park land. While it may be controversial, the presence of grazing on the land at Point Reyes National Seashore has provided a number of ecological benefits, such as a greater number and variety of native grasses as compared to areas that have suffered shrub invasion where grazing was removed (Rilla and Bush 2009). In recent years there have been a number of issues at Point Reyes that have escalated controversy and caused a fracturing between the tenants at Point Reyes National Seashore, the National Park Service, park visitors and environmental groups. Some of the recent issues causing tension include the removal of Drakes Bay Oyster Company from the park, ranchers being denied renewal of their leases at the seashore, Tule elk competing with ranchers’ cattle herds, and an outdated general management plan. However, despite the disputes over the landscape that have been building in the last few years, the parties all agree that Point Reyes is unique place worthy of protection.

After studying the area since the 1930s as a potential location for a public recreational area to serve the residents of the growing city of San Francisco, in 1962 in an attempt to stave off a potential housing development, the National Park Service decided to establish the Point Reyes National Seashore (PRNS) as a 53,000 acre recreational area, including a 21,000 acre pastoral zone, located on the Point Reyes Peninsula in Marin County, California. In 1976 an additional 25,370 acres were designated as the Phillip Burton Wilderness Area at Point Reyes National Seashore. Within the PRNS and wilderness area 8,003 acres were designated as potential wilderness additions. Today PRNS is a 71,028 acre park preserve. As previously mentioned, Point Reyes has continued to be an area of mixed use between commercial and recreational activities, allowing for some agricultural uses to continue on the protected lands.[1] As noted by Deur and Mark, “The continued operations of dairies and ranches became an integral part of the park, and the NPS found itself having to work with ranchers directly as neighbor and often owner. When the NPS carried out purchases of ranch land, it usually granted reservations of use and occupancy for a period of 25 years to those who wished to continue ranching” (Deur and Mark 2011). Although these uses were allowed to remain, they were not without restrictions and remained exceptions, giving less power and control those who worked the land.

In a report on resident communities in national parks, Douglas Deur, University of Washington researcher, and Stephen R. Mark, NPS Historian, note the balancing act that the NPS has been conducting over the years between the expectations of a pristine landscape by park visitors and the need to respect the communities that reside in and help shape the parkland. In reviewing four case studies for the management of agriculture in national parks, Deur and Mark point to Point Reyes National Seashore as an “outstanding example” of a thriving mixture of agriculture and parkland. However, the authors state, “…as landlord at Point Reyes, the NPS continues to be challenged by the complexities inherent with maintaining economically viable ranch operations within a recreation area where visitors see natural values as predominant. Many of the ranchers have nevertheless viewed the NPS presence as beneficial, since the peninsula also represents the only large block of land in Marin County remaining in agricultural production”(Deur and Mark 2011). Deur and Mark conclude with describing Point Reyes as an experiment of sorts between a combination of private and public uses in order to please the multiple stakeholders.The 1964 Wilderness Act, that was used to establish the Phillip Burton Wilderness Area at Point Reyes National Seashore in 1976, envisioned wilderness as an, “…area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain…without permanent improvements or human habitation, which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions…” (Public Law 88-577). While this was the vision of wilderness seen through the eyes of Wilderness Society’s Howard Zahniser, the author of the Act, the Act also contained many exceptions, such as non-conforming prior uses. Point Reyes never quite fit the ideal model of a wilderness area, as it was the first area to receive the designation of potential wilderness lands. While the NPS may have a history of accepting alternative uses within the park land at Point Reyes, it appears with recent tensions and decisions that they are headed down the traditional path of park management, one that excludes people, other than tourists, from their vision.

Environmental historian, Laura A. Watt, has been researching the case of Point Reyes National Seashore for over a decade. She has written a number of articles on Point Reyes and has a forthcoming book on the subject, The Paradox of Preservation: Wilderness and Working Landscapes at Point Reyes National Seashore. Watt’s work explores the controversy over Drakes Bay Oyster Company[2] through the lens of preservation and the ideas that surround what a park ‘ought’ to be. In order to understand the progression of issues at Point Reyes, Watt reviews the ideology that underpins the historical development of the National Park Service and the United States’ ideals of park land and the effect these ideals have had on the establishment and management of PRNS.

Point Reyes is a particularly distinctive unit in the U.S national park system, comprised of both a wilderness area and working landscapes as park land. While the disputes over the space have been increasing recently, much of the root of the tension lies in the designation of the space. The National Park Service has the challenging mission of both protecting the space while also providing for the enjoyment of the visitors and overseeing the commercial uses of the protected land. They have often chosen in the past to view society as separate from nature, fostering the perception that the two are incompatible, and thus dictating who is allowed access to a particular resource. In her article, “The Trouble with Preservation, or, Getting Back to the Wrong Term for Wilderness Protection: A Case Study at Point Reyes National Seashore”, Laura Watt provides several propositions to help counteract the myth of wilderness as separate from that of human use. She proposes the use of a continuum of standards for wilderness determined by the degree to which the area has been inhabited and people have manipulated the land, rather than an all or nothing approach, a sentiment shared by William Cronon (Cronon 1996). Watt also suggests that, “the NPS and other land management agencies could help to heal this disconnect between nature and culture by encouraging the public to understand the human history of natural areas, even while continuing to manage wilderness values”(Watt 2002). Nevertheless, the decisions of who is allowed access, and of what type, in a conserved space can have profound impacts not only on the visitors to the space, but on the residents that depended on that space for their livelihoods.

References

Cronon, William. 1996. “The Trouble with Wilderness; Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” In Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, edited by William Cronon, 69–90. New York/London: W.W. Norton and Company.

DeRooy, Carola, and Dewey Livingston. 2008. Point Reyes Peninsula: Olema, Point Reyes Station, and Iverness. San Francisco: Arcadia Publishing.

Deur, Douglas, and Stephen R Mark. 2011. Resident Communities and Agriculture in National Parks : An Assessment and Prospectus.

Rilla, Ellie, and Lisa Bush. 2009. The Changing Role of Agriculture in Point Reyes National Seashore. Novato. https://ucanr.org/sites/uccemarin/files/31000.pdf.

Watt, Laura A. 2002. “The Trouble with Preservation, Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Term for Wilderness Protection: A Case Study at Point Reyes National Seashore.” APCG Yearbook 64: 55–77.

Notes

[1]. For further detail on the acts establishing PRNS and the Wilderness area, see Laura A.Watt’s

forthcoming book, The Paradox of Preservation: Wilderness and Working Landscapes at Point Reyes National Seashore.

[2]. The Drakes Bay Oyster Company controversy involves the issue of whether or not the Department of the Interior would reinstate the company’s lease to commercially harvest oysters at PRNS. The decision was made to expel Drakes Bay Oyster Company from the park in December 2014. While outside the scope of this paper, this is a fascinating case that can be explored further in Laura A. Watt’s forthcoming book, The Paradox of Preservation: Wilderness and Working Landscapes at Point Reyes National Seashore.