Bay Area Open Space Is ‘Not’ Open Space

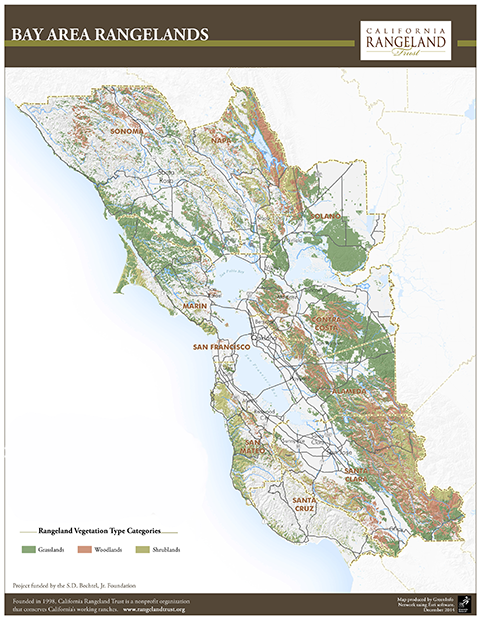

The San Francisco Bay Area has more open space within its borders than any other metropolitan area in the United States, an intriguing state of affairs for a regional population approaching nine million people. While so much open space provides a scenic landscape and exceptional opportunities for outdoor recreation including hiking, biking, horseback riding, and hang gliding, it also supports the area’s most prevalent land use. From Santa Clara to Sonoma County — on private lands, regional parks, on habitat conservation and watershed lands — cattle ranching continues as the number-one land use in this famed tourist destination and hotbed of the knowledge economy and high tech industry. Whether the working ranches are on public or private land, many Bay Area ranchers represent a fourth, fifth, or sixth generation stewarding the land and their livestock, drawing on older traditions and practices of pastoralists and primary producers. Ranching or working rangelands describe the land use of over 1.7 million acres of the Bay Area’s 4.5 million acres of open space (PlanBayArea.org). Rangelands that produce both livestock products and ecosystem services are known as “working landscapes” in the Bay Area (Fig 1).

Ranching supports the Bay Area’s incredible biological diversity at the landscape and pasture level. Thirty-three percent of California’s natural communities are found in the Bay Area on only five percent of the state’s land, which makes this one of the nation’s most important biological hot spots (Bay Area Open Space 2012). At the landscape level, ranching maintains extensive open landscapes that were originally grassland or a tree-grass mosaic shaped by the burning practices of native Californians (Fig 2) (Diekmann et al. 2007). Oaks that are the most common native tree provide abundant acorns and rich game habitat. Spanish-Mexican colonists used the grasslands and woodlands for extensive livestock grazing well into the 1840s, and established some of the largest ranches in California. The Pt. Reyes National Seashore derives from what was originally a Mexican land grant.

Large patches of open grazed grassland support a species-rich birdlife community, including along the southern range a slowly recovering population of the California Condor (Gymnogyps californianus). At the pasture level, ranching provides for biodiversity through grazing and associated rancher stewardship. Grazing reduces annual plant biomass, influences vegetation composition, affects vegetation structure, and provides the patches of bare ground needed by some species, such as the Ohlone tiger beetle (Cicindela ohlone) (Cornelisse et al. 2013). The endangered Bay checkerspot butterfly (Euphydryas editha bayensis), California tiger salamander, burrowing owls (Athene cunicularia), and kit fox (Vulpes macrotis mutica) all benefit from livestock grazing, which manages vegetation and preserves needed habitat (Bartolome et al. 2014). In fact, the exclusion of grazing has resulted in the extirpation of some populations of these species from “protected sites” (Barry et al. 2015). Rancher stewardship includes development and maintenance of livestock water sources including stock ponds, pest management, debris clean-up, and forage improvement. In the San Francisco Bay region, ponds developed for livestock water provide half of the available habitat for the endangered tiger salamander (Ambystoma californiense).

Despite being the area’s most prevalent land use, cattle ranching largely goes unnoticed by much of the public. Ranching operations typically need up to 15–20 acres per cow per year. Few people realize that many of the Bay Area’s open spaces are managed with grazing until they come on to cattle grazing in a regional park. While there is support for ranching as a way of life with long traditions, the management of vegetation that without grazing could prove a fire hazard is a shared goal, brought starkly to light by the Oakland-Berkeley firestorm of 1991 that killed 25 people and destroyed some 3,300 dwellings at a cost of more than $1.5 billion. Today, significant areas of the 8,180 acre Stanford University campus are grazed for vegetation control, as are upper reaches of the 1,232 acres UC Berkeley campus, often by hired goat herds (Stein 2015).

Bay Area ranchers are particularly aware of the public’s interest in the rangelands they manage (Fig 3). At least partly because they often rely on leases from parks and conservation lands to complement their private holdings, many ranchers have learned to manage for native plant and animal species and fire hazard control. The California Rangeland Conservation Coalition, a statewide group focused on bringing ranchers, scientists, environmentalists, range professionals, and agencies together to support ranching and the conservation of grazing lands, enjoys strong support among Bay Area ranchers (https://carangeland.org). Working landscapes are also a prominent part of the Bay Area’s “foodscape,” widely appreciated by food-conscious Bay Area residents. On privately-owned ranch lands, ranchers use wildlife-friendly practices and improvements, sometimes partnering with the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the California Department of Wildlife, or local Conservation Districts. Many have mitigation or conservation easements on their properties, providing more habitat, watershed, and connectivity than can be provided on public lands alone.

A recent study used social media to understand public interest and perceptions of cattle grazing on parklands (Barry 2014). Many park users visiting Bay Area grazed parks shared positive views about cows and grazing on Flickr™ expressing an enjoyment of the pastoral scene and their recognition the grazing animals as “happy cows.” A few negative comments (under two percent) made it clear that some park users, especially those with dogs, are bothered by manure. Of greater concern to park managers, some park users expressed a fear of cows. Some stated a desire to overcome their fear but there seemed to be uncertainty about what could happen or how to respond to the presence of livestock. If you run across cattle on your Bay Area wanderings, give them their space, and keep dogs far away, since to livestock a dog is a predator. Cows really just want to eat the grass and will generally ignore you if you let them. Park managers may be able to overcome negative perceptions and fear of cows on public lands via education. With over 2.5 million visitors to grazed parks per year in the Bay Area, there is a growing opportunity to educate and explain why Bay Area open space is not open space but instead, constitutes well-stewarded places supporting and benefiting from cattle and sheep ranching.

Further Reading and References

Barry, S. (2014). Using Social Media to Discover Public Values, Interests, and Perceptions about Cattle Grazing on Park Lands. Environmental Management 53: 454-464. DOI: 10.1007/s00267-013-0216-4

Barry, S., L. Bush, S. Larson, and L. Ford. (2015). Understanding Working Rangelands: The Benefits of Livestock Grazing California’s Annual Grasslands. University of California ANR Publication 8517. 7 p.

Bartolome, J., B. Allen-Diaz, B., et al. (2014). Grazing For Biodiversity in California Mediterranean Grasslands. Rangelands 36(5): 36-43. DOI:10.1525/california/9780520252202.003.0020

Bay Area Open Space Council. (2012). Golden Lands, Golden Oppoturnity. Prserving vital Bay Area lands for all Californians. Accessed Nov 2015.

Cornelisse, T. M., M.K. Bennett, & D. K. Letourneau. (2013). The Implications of Habitat Management on the Population Viability of the Endangered Ohlone Tiger Beetle (Cicindela ohlone) Metapopulation. PLoS ONE, 8(8), e71005. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071005

Diekmann, L., L. Panich, and C. Striplen. (2007). Native American Management and the Legacy of Working Landscapes in California. Rangelands 29 (3): 46-50. DOI:10.2458/azu_rangelands_v29i3_diekmann

PlanBayArea.org [Association of Bay Area Governments and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission]. (2013). Plan Bay Area 2040 Draft Environmental Impact Report. Accessed Nov 2015.

Stein, D. and Facebook. 2015. Moving Goats on UC Berkeley Campus, Video Clip,

Sheila Barry is Bay Area Natural Resources/Livestock Advisor and Santa Clara County Director for UC Cooperative Extension

Paul F. Starrs is Professor of Geography, University of Nevada, Reno

Lynn Huntsinger is Professor, Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, UC Berkeley