Louisiana’s Turn to Mass Incarceration: The Building of a Carceral State

The history of the Louisiana penal system is marked through crisis. For the majority of the 20th century such crises revolved around the state’s singular prison, the Louisiana State Penitentiary, commonly referred to as Angola. Having long been known as the “bloodiest prison in the nation,” the prison entered into an unmatched crisis of legitimacy in the 1970s. Conditions were wretched and stabbings and escapes were monthly affairs.[1] Within this climate, scores of incarcerated people filed lawsuits against the penitentiary. In 1975, U.S. Magistrate Frank Polozola found in favor of four Black prisoners at Angola, Arthur Mitchell Jr., Hayes Williams, Lee E. Stevenson, and Lazarus D. Joseph, who had filed a lawsuit against Angola in 1971 for numerous constitutional issues including medical neglect, unsafe facilities, religious discrimination, racial segregation, and overcrowding. Polozola declared the penitentiary to be in a state of “extreme public emergency.”[2] Massive changes were ordered in the name of restoring incarcerated people’s constitutional rights.[3] For the next several years, the Louisiana penal system, including parish jails, were under the jurisdiction of federal court orders.

While many issues were brought to the forefront through this legal ruling, overcrowding became the central issue for the Department of Corrections (DOC) and the broader state. The federal courts ordered that Angola’s prison population be reduced from over 4,000 prisoners to 2,641 prisoners within a few months time.[4] In response, the DOC advocated for the “decentralization” of Angola through creating small rehabilitation focused prisons and the potential for shuttering Angola altogether. With time at a premium, the DOC scrambled to find and convert a wide range of surplus state property from schools, to hospitals, to even a decommissioned navy ship into new prisons.[5] Recent infusions of federal funds in the form of Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA) grants and the exponential increase in state revenues do to the global jump in oil prices following the 1973 OPEC price hike meant that funding such conversions was of little concern to the state. However, the DOC had extreme difficulty in attaining the support of local residents who routinely protested new prison plans.[6] Mobilized via fears of “dangerous criminals” that they believed would not only make their communities unsafe but would also lower their property taxes, communities from Caddo Parish to Bossier City to New Orleans East were successful in keeping out new satellite prisons.[7] At the same time, parish jails throughout Louisiana entered into their own state of emergency as they were forced to accommodate the hundreds of prisoners prohibited from being transferred to Angola inciting anger in local sheriffs statewide.[8] In response to these challenges, DOC Secretary Elayn Hunt and Angola Warden C. Paul Phelps, who had long been concerned with the rise of “lifers” at Angola, joined the call led by Angola’s incarcerated activists for a different solution to the overcrowding crisis: the early release of prisoners.[9]

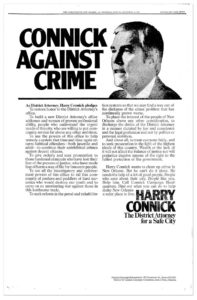

However, the New Orleans D.A. Harry Connick was adamantly against such proposals. At the time, Connick was in the process of building his career upon the racialized tough on crime politics sweeping the nation. He routinely attacked DOC officials in the press for advocating early release and alternatives to incarceration.[10] In fact, in the same months the federal court orders were coming down, he successfully pushed for more punitive policies and practices through working with the NOPD to attain LEAA grants to expand policing powers.[11] In addition, he personally drafted dozens of draconian crime bills that instituted mandatory sentencing and reduced good time and parole eligibility, which the increasingly law and order state legislature was more than happy to pass.[12] With arrest rates going up,[13] sentencing becoming harsher and the number of people being paroled steadily dropping, overcrowding pressure intensified across the state.[14] Thus, Louisiana was confronted with a range of different pushes and pulls, from federal court rulings, to parish level politics, to active disagreement among state and city officials, to global political economic realignments and new federal monies, as state leaders attempted to figure out the future direction of the penal system.

By the decade’s end, it was clear that Louisiana’s politicians were attempting to build their way out of the overcrowding crisis. Three new prisons had been built with more on the way and thousands of new beds were added to Angola more than doubling the state’s prison population from 3,550 people in 1975 to 8,661 people in 1980.[15] This unprecedented carceral state building project was emboldened and buttressed by the 1980 election of David Treen to governor who had explicitly campaigned on a tough on crime platform and by Polozola, now a federal judge, who began to mandate that Louisiana deal with its continual overcrowding crisis through expanding the prison system.[16] Yet, as incarcerated activists with The Angolite and the Lifers Association as well as free world prison reformers argued at the time, growing the state’s carceral apparatus did not solve the crisis but propelled further overcrowding.[17] The ongoing overcrowding at the prisons further increased pressure on dozens of parish jails as they were yet again, relied on to house thousands of state prisoners, leading to overflowing jails from New Orleans to Lafayette.[18] In the case of New Orleans, the situation became so dire that in the summer of 1983 then Sheriff Foti erected a tent jail in the face of overcrowding at the city jail, Orleans Parish Prison (OPP).[19]

While sheriffs everywhere were frustrated by this situation, their response to such overcrowding was markedly different in the early 1980s than it had been in the mid-1970s. When parish jails had filled to capacity in response to the 1975 court orders, sheriffs lobbied to get state prisoners out of their jails.[20] But only a few years later, while sheriffs collectively petitioned the state to get so-called “violent offenders” out of their jails they also pushed for funds to renovate and expand the parish jails to make space for both folks awaiting trial as well as state prisoners.[21] We can understand this shift from a number of vantage points. While in 1975 the overcrowding crisis appeared to be temporary, by the early 1980s there was no sign of incarceration rates letting up as Governor Treen and the state legislature continued to press for the passage punitive crime bills. In addition, when parish officials had been compelled to release people to stay within the population limits set by Judge Polozola, the media attacked them for letting “criminals” loose into the streets.[22] With both politicians and the media employing such fear-mongering tactics, political will was on the side of jail expansion versus early release or alternatives to incarceration as a solution to the overcrowding. In fact, Governor Treen’s decision to prioritize jail construction over education, healthcare, and levees in the state budget was “not out of a desire to make life easier for these convicts but to make sure that no judge feels compelled to release somebody back into society who should not be there just because prisons are overcrowded.”[23] And indeed, as the Louisiana Coalition on Jails and Prisons would highlight in their decarceration campaigns throughout the 1980s, the atrocious conditions within jails persisted alongside their shiny new renovations.[24]

Sheriffs’ desires to build up their parish jails aligned not only with the dominant law and order politics of racial neoliberal governance, but also with the economic conditions confronted by the state. When sheriffs were first required to take in state prisoners in 1975 it was a financial burden since the DOC was paying sheriff departments a per diem rate of only $4.50/day per prisoner.[25] But as the overcrowding crisis wore on, local parish officials, including sheriffs, successfully petitioned the state to increase the per diem to $18.25 by 1980.[26] The higher per diem rate made sheriffs much more amenable to housing state prisoners as they were able to use the funds to build out their departments’ carceral infrastructure. Sheriffs throughout the state leveraged such jail growth to expand their political power both within their own parishes and through the Louisiana Sheriffs’ Association.

What’s more is this per diem system met the financial needs of the broader state as well. Since the Jim Crow regime, the state had been loathe to finance the penal system.[27] To meet mandates of the federal courts, the state was required to increase funding to the Department of Corrections on an unmatched scale. The DOC budget during this time shot up from $20 million in 1974 to $135 million by 1982 with tens of millions of dollars spent on new prison construction which, as previously mentioned, was easily funded for the first several years through unexpected oil revenues.[28] Yet as oil dependent economies are notoriously precarious, Louisiana entered into a fiscal crisis in the early 1980s in response to the global oil slump.[29] With the state’s fiscal crisis and accompanied economic recession deepening throughout the 1980s, state officials sought new solutions for maintaining carceral growth. While state officials turned to debt-financing for new carceral construction, the state’s inability to cover prison operating costs with such debt schemes put the state in a conundrum. Although prisoners and decarceration activists offered the solution of the state curtailing law and order politics and instituting mass parole as other states had in similar situations, Louisiana turned to upping its reliance on the parish jail system as a more politically and financially viable option. [30] As the per diem rate was much lower than the costs of keeping prisoners incarcerated in state prisons, the state forged ahead with creating multi-decade cooperation endeavor agreements between the Department of Corrections and a slew of primarily rural parishes to house the lion’s share of state prisoners. What had started out as a temporary spatial fix had become the long-term geographic solution to prison overcrowding.

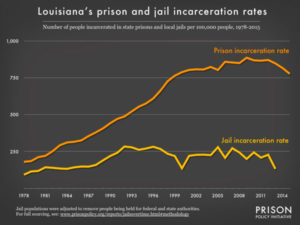

By the time Louisiana gained the title of having the highest incarceration rate in the nation in the late 1990s, almost half of the state’s prisoners were behind bars in parish jails with New Orleans’ OPP at 7,000 plus beds, the largest carceral facility in the state.[31] Although when the jail was first enlarged to this mammoth size, its jail population had stabilized to around 5,000. Yet only five years later, the jail was at capacity. Three thousand of those locked away were state prisoners while a combination of people awaiting trial who could not afford to pay exorbitant bail bonds, individuals serving municipal offenses, a growing number of juveniles, and INS immigrant prisoners held through federal contracts filled the remaining 4,000 beds. Many of those held behind OPP’s walls at Tulane and Broad avenues were targets of intensified policing crackdowns during the 1990s. Although officially most crime was in decline during the 1990s in New Orleans, the escalation of fear-based, racially-coded news media made controlling the city’s supposed lawlessness a priority for city leaders who were concerned about the negative impacts of such reporting on the tourist economy.[32] Under the administration of Mayor Marc Morial and his Police Superintendent Richard Pennington, the NOPD implemented a form of “community policing” to saturate the city’s housing projects, the French Quarter, and Downtown Development District with law enforcement.[33] This spatial strategy for law enforcement illuminated the interlaced primacy of “sanitizing” the city’s tourist epicenters of the homeless, youth, queer and trans people, and sex workers as well as containing and controlling Black working class spaces. Such policing tactics served to fill OPP to the brim by the time Hurricane Katrina made landfall in the Crescent City on August 29, 2005 and prisoners were abandoned by the state to flooded cells.[34]

In the dozen years since the levee breaks, attention has finally begun to be given to the crisis of mass incarceration in Louisiana. The sustained community organizing of the Orleans Parish Prison Reform Coalition (OPPRC) successfully campaigned for OPP to be rebuilt on the much smaller scale of 1438 beds in 2010 while the creation of the Independent Police Monitor’s Office and the Department of Justice’s implementation of a consent decree on the NOPD has tempered police misconduct.[35] This past summer organizations such as VOTE (Voice of the Experienced) were successful in getting the state legislature to pass ban the box legislation and raising the age that juveniles can be tried as adults.[36]

However, these local gains have never been final victories. Public defenders in Louisiana continue to be woefully underfunded. The current New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu has been pushing a law and order surveillance plan for the city while the New Orleans city council is bending towards the will of Sheriff Marlin Gusman that the city needs to raise the jail cap for a “Phase Three” of construction at OPP.[37] Several front-runners in the upcoming mayoral and city council elections are following old tough on crime scripts in making expanding the NOPD the number one piece of their political platform. The current Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry recently sent his own rogue band of state troopers to police New Orleans and has been working with AG Jeff Sessions to repeal the consent decree governing the NOPD.[38] AAG attendees are likely to catch a glimpse of the French Quarter Management District’s private security vehicles that work in alliance with the NOPD and state troopers. Their explicit mandate from the French Quarter business leaders is to crack down on perceived sex workers, transgender individuals, street musicians, and others they deem “undesirable” to the imperatives of racial capital.

While the future of the Louisiana carceral state remains uncertain, it is clear that understanding the multiscalar factors that have produced the current crisis of mass incarceration is a critical starting point to undoing this systematic violence and striving towards the still unrealized project of abolition democracy.

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0025

[1] “State Prison Inmate Slain in Stabbing,” State Times (Baton Rouge, LA), July 18, 1974, 9-A.

[2] Williams v. McKeithan C.A 71-98 (M.D.La, 1975), US Magistrate Special Report; Gibbs Adams, “Federal Court Orders State Prison Changes,” The Advocate (Baton Rouge, LA), April 29, 1975. Judge West backed up Polozola in ordering sweeping changes. However, it is worth noting that Polozola had nothing to say about one of the plaintiffs main complaints: solitary confinement. “4 Inmates Ask Changes in Pen Safety Reform Plan,” State Times (Baton Rouge, LA), May 6, 1975.

[3] Williams v. McKeithan C.A 71-98 (M.D.La, 1975), Judgement and Order.

[4] Louisiana Prison System Study, 29, Governor’s Office Long Range Prison Study Files, 1972-1980, Box 1, Louisiana State Archives.

[5] C.M. Hargroder, “7 Prison Sites Proposed,” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), September 16, 1975; “World War II Troopship May Be Used As Floating Louisiana Prison,” Monroe Morning World (Monroe, LA), October 26, 1975.

[6]“Executive Budget 1974-1975, Vol. 1,” Box 1: Executive Budget 1975-1980, State Budget Reports 1970-1989, Louisiana State Archives (LSA); “State of Louisiana Budget Fiscal Year 1974-1975,” Box 3, State Budget Reports 1970-1989, LSA; “State of Louisiana Budget Fiscal Year 1975-1976,” Box 3, State Budget Reports 1970-1989, LSA.

[7] Bonnie Davis, “Residents Will Protest Use of Carver School as Prison,” Shreveport Times (Shreveport, LA), July 24, 1975; Lynn Stewart, “State May Seize Site in Caddo for Prison,” Shreveport Times (Shreveport, LA), August 19, 1975; “Bossier Prison Site Reported Ruled Out,” Morning Advocate (Baton Rouge, LA), March 19, 1976; Richard Boyd, “Council Vows to Fight East N.O. Prison Facility” States Item (New Orleans, LA), April 23, 1976; Patricia Gorman, “Homes Closed to Inmates” States Item (New Orleans, LA), April 30, 1976.

[8] Roy Reed, “Louisiana’s Jails Are Being Packed,” New York Times (New York, New York), September 18, 1975; Pierre V. DeGruy, “ ‘State of Emergency’ at Parish Jail—Foti, “The Times Picayune (New Orleans, LA), October 16, 1975.

[9] “Two Year Time Limit Termed Impossible for Angola Changes,” State Times (Baton Rouge, LA), June 17, 1975; Tommy Mason, “Lifer’s,” The Angolite, August 1975, 23; John McCormick, “Legal Action: Our Goodtime Law May Be Changed,” The Angolite, September 1975, 1-2.

[10] Associated Press, “Inmate Release Policy Blasted,” Morning Advocate (Baton Rouge, LA), June 9, 197; Ed Anderson, “Connick Attacks Parole Board Plan,” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), October 28, 1975.

[11] “ ‘Career Criminal’ Bureau for N.O.” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), March 19, 1975.

[12] Jack Wardlaw, “Connick Wins Anti-‘Good Time’ Battle in House,” State Item (Baton Rouge, LA), July 2, 1975; 12-a; Pierre V. DeGruy, “Connick Endeavors in Legislature Pay Off: Entire Package is Passed” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), July 31, 1975.

[13] “Jail Overload Credited to Police Work,” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), April 17, 1980.

[14] “Criminals Face Harsher Penalties as New Law Takes Effect,” State Item (Baton Rouge, LA), September 17, 1975.

[15] Louisiana Prison System Study, 4, Governor’s Office Long Range Prison Study Files, 1972-1980, Box 1, LSA; Louisiana Commission on Law Enforcement, “The Data: Prison Crowding in Louisiana, 1988,” Folder 9: Prison Reform Reports, Remarks, Statements 1987-1988, Box 3, Rev. James Stovall Papers, Louisiana State University.

[16] Treen: ‘Going to Be Touch to Get a Pardon From Me’ “ Alexandria Town Talk (Alexandria, LA), March 9, 1980; Gibbs Adams, “State Prisons Must Expand,” Morning Advocate (Baton Rouge, LA), May 19, 1983.

[17] “Remarks by Jack D. Foster, Project Director Law and Justice Section, The Council of Staet Governments Before The Governor’s Pardon, Parole, and Rehabilitation Commission,” May 9, 1977, Folder 2: Governors Pardon, Parole, and Rehabilitation Commission Remarks and Reports, Box 3, Rev. James Stovall Papers, Louisiana State University; “The Crowded Cage,” The Angolite, November/December 1983, 35-60.

[18] “Orleans Prison Above Inmate Ceiling for 3 Months,” State Times (Baton Rouge, LA), May 17, 1983; Nanette Russell, “District Attorney Angry State Prisoners in Jails,” Lafayette Advertiser (Lafayette, LA), June 28, 1983.

[19] “Foti Gets OK to Put Inmates in Tents,” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), June 14, 1983.

[20] Pierre V. Degruy, “Packed Prison Feared,” The Times Picayune (New Orleans, LA), September 12, 1975.

[21] Memo from Carey J. Roussel to Donald G. Bollinger, March 17, 1981, Folder 1: Public Safety 1981, Box 815: P 1981, David Treen Papers, Louisiana Research Collection, Tulane University; “Sheriff Layrisson Angry Over Jail Fund Postponement,” Vindicator (Hammond, LA), May 25, 1983.

[22] Monte Williams, “Crowded Jails Let Criminals Free,” Daily Iberian (New Iberia, LA), June 12, 1983.

[23] “Comments on Governor David C. Treen’s Criminal Justice Package for Possible Use by President Reagan in his September 28 Speech to the International Association of Chiefs of Police,” Folder 4: Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice 1981, Box 796: L 1981, David Treen Papers, Tulane University.

[24] Louisiana Coalition on Jails & Prisons, “Jail Project Update” pamphlet, 1981, Folder: Louisiana Coalition, Box 2, Southern Coalition on Jails and Prisons Records, 1974-1980, The Southern Historical Collection, Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Louisiana Coalition on Jails & Prisons, “Louisiana Jails” pamphlet, n.d., Folder: Louisiana Coalition, Box 2, Southern Coalition on Jails and Prisons Records, 1974-1980, The Southern Historical Collection, Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[25] “Legislative Digest,” The Angolite, September/October 1978, 9.

[26] Memo from C. Paul Phelps to William A. Nungesser, October 3, 1980, Folder 8: Corrections 1980, Box 666: C 1980, David Treen Papers, Tulane University.

[27] Mark T. Carleton, Politics and Punishment; the History of the Louisiana State Penal System (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971).

[28] “Executive Budget 1974-1975, Vol. 1,” 9, Box 1, State Budget Reports 1970-1989, Louisiana State Archives; “Louisiana State Budget 1982-1983,” 39, Box 4, State Budget Reports 1970-1989, Louisiana State Archives;

[29] “Executive Budget Program 1982-1983 Vol 1,” A11, Box 2: Executive Budgets 1980-1985, Louisiana State Archives. For more on the precarity of oil economies at this time see Petter Nore and Terisa Turner, Oil and Class Struggle (London: Zed Press, 1980).

[30] “The Moment of Truth” The Angolite, May/June 1982, 12.

[31] Southern Legislative Conference, Louisiana Legislative Fiscal Office, Adult Corrections Systems 1998, by Christopher A. Keaton, (Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1999), 7-8.

[32] Chris Adams, “Tragedy Marks a Night of Crime,” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), August 5, 1990; Walt Philbin, “Shooting Sets Murder Record,” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), October 23, 1990; Michael Perlstein, “Beyond the Bullet – Murder in New Orleans,” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), July 1, 1993; Sheila Grissett, “Murder Rate in N.O. Exceeds One a Day,” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), July 17, 1993; Sheila Stroup, “When Will It All End?” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), July 26, 1994. International Association of Police Chiefs, The New Orleans Police Department Revisited, June 29, 1993, 2-8, Marc H. Morial Papers. Box 33, Folder 1: Morial Transition The New Orleans Police Department, Revisited 1993, Amistad Research Center.

[33] Building New Orleans Together: City of New Orleans 1997 Annual Report, 1997, 7, Box 43, Folder 7: Mayoral City of New Orleans Annual Reports, Marc H. Morial Papers 1994-2002, Amistad Research Center.

[34] ACLU National Prison Project, Abandoned and Abused: Orleans Parish Prisoners in the Wake of Hurricane Katrina, report (2006).

[35] https://www.nola.gov/nopd/nopd-consent-decree/

[36] This is not to be confused with the widely lauded bipartisan package of prison reform bills that passed the Louisiana legislature last summer, which has served to primarily tinker with the penal system rather than make meaningful reforms. “Louisiana’s Parole Reform Law Continues a Positive Trend in Criminal Justice Reform,” Voice of the Experienced, accessed September 26, 2017, https://www.vote-nola.org/archive/louisianas-parole-reform-law-continues-a-positive-trend-in-criminal-justice-reform.

[37] Emily Lane, “At Orleans Jail, Monitor and Judge See ‘light at the End of the Tunnel‘,” NOLA.com, June 08, 2017, accessed September 26, 2017, .

[38] Jim Mustain, “Attorney General Jeff Landry Slams Mitch Landrieu, Says New Orleans ‘more Dangerous than Chicago’,” The Advocate, January 07, 2017, accessed September 26, 2017; Richard Rainey, “AG Landry Met with Trump, Sessions; Discussed Law Enforcement,” NOLA.com, March 01, 2017, accessed September 26, 2017.