Essential Geographies of New Orleans Music

Part 2: Rhythms, Blues, and the Infinite Potential of Congo Square

What comes after jazz? How does a city reprise its collective creation of the Americas’ most original and distinctive art form? Part 2 of this essay surveys happenings in New Orleans music since the emergence of jazz around the turn of the twentieth century. For a take on earlier developments, check out Part 1 before working your way back here. Each of these essays, it is important to note, are highly personal accounts, framed and embellished by my own encounters and experiences in the Crescent City and points south. In this second part, I work to demonstrate how New Orleans drew from its fundamental links with the African Diaspora and Atlantic Worlds to influence many of the major shifts in American popular music over the twentieth century. I hope these brief discussions help set the mood for geographers attending the 2018 AAG Annual Meeting held in New Orleans as the city fêtes its tricentennial. These accounts also provide context for many of the musical acts and styles on display at the French Quarter Fest, the city’s gratis outdoor music festival that coincides with the AAG meeting.

Jazz is not an only child. On the contrary, the birth of jazz as a musical and economic form and force was but one flare-up in a long and gradual process of musical innovation and exchange in New Orleans. As myriad musical forms collected under a broad jazz umbrella, those various styles steadily evolved and expanded in a never-ending flow of accumulation and origination. Sustaining its status as a globally eminent cultural hearth, New Orleans continues to avail its strategic situation at the confluence of the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico to churn out innovative and influential music.[i]

As the jazz sound bubbled up from the streets around the turn of the century, the city’s (in)famous red-light district, Storyville, provided steady gigs for the growing class of New Orleans musicians. And it was during the district’s twenty-year existence (1897-1917) that two of the city’s stalwart musical institutions assumed their distinctive styles. Brass bands typically played rowdy gin mills, restaurants, and saloons, while solo piano players worked the parlor houses of the district’s many brothels and cabarets. Beginning with legendary forebears Tony Jackson and Jelly Roll Morton, piano “professors” remain an iconic leitmotif in the city’s musical culture. Moreover, a sampling of the city’s more prominent pianists helps trace a particular evolution of New Orleans’ musical innovations over the twentieth century, from Jelly Roll Morton to Tuts Washington to Fats Domino to Allen Toussaint; and from Professor Longhair to Art Neville to James Booker to Dr. John.[ii]

As jazz became an international phenomenon in the early twentieth century, New Orleans maintained its outsized influence by simultaneously nurturing its jazz scene and fomenting new innovative expressions. Emanating from Congo Square in the centuries prior, the syncopated rhythms that became essential in early jazz remained the city’s backbeat, and toward the mid-twentieth century provided the foundation for New Orleans rhythm and blues, and in turn, rock and roll. The diasporic habanera rhythms underlying jazz, what Jelly Roll called “the Spanish tinge,” along with the derivatives rumba and mambo, went on to become key elements in the forerunning rhythm and blues of Professor Longhair. First showcased in his 1949 debut, “Blues Rhumba,” the Fess’s rollicking two-hand piano style melded many of the musical innovations that had traveled down the river or across the Gulf to New Orleans. An admirer of both Hank Williams and the Cuban “Mambo King” Pérez Prado, Longhair kept time with Afro-Cuban clave polyrhythms on his left hand, while riffing barrelhouse blues from the upland South on his right. The Fess thus integrated and indeed embodied the far-flung musical traditions that coalesced in New Orleans, uniting the call-and-response blues of the Mississippi Delta with the Afro-Caribbean rhythms circulating in the broader Atlantic World.[iii]

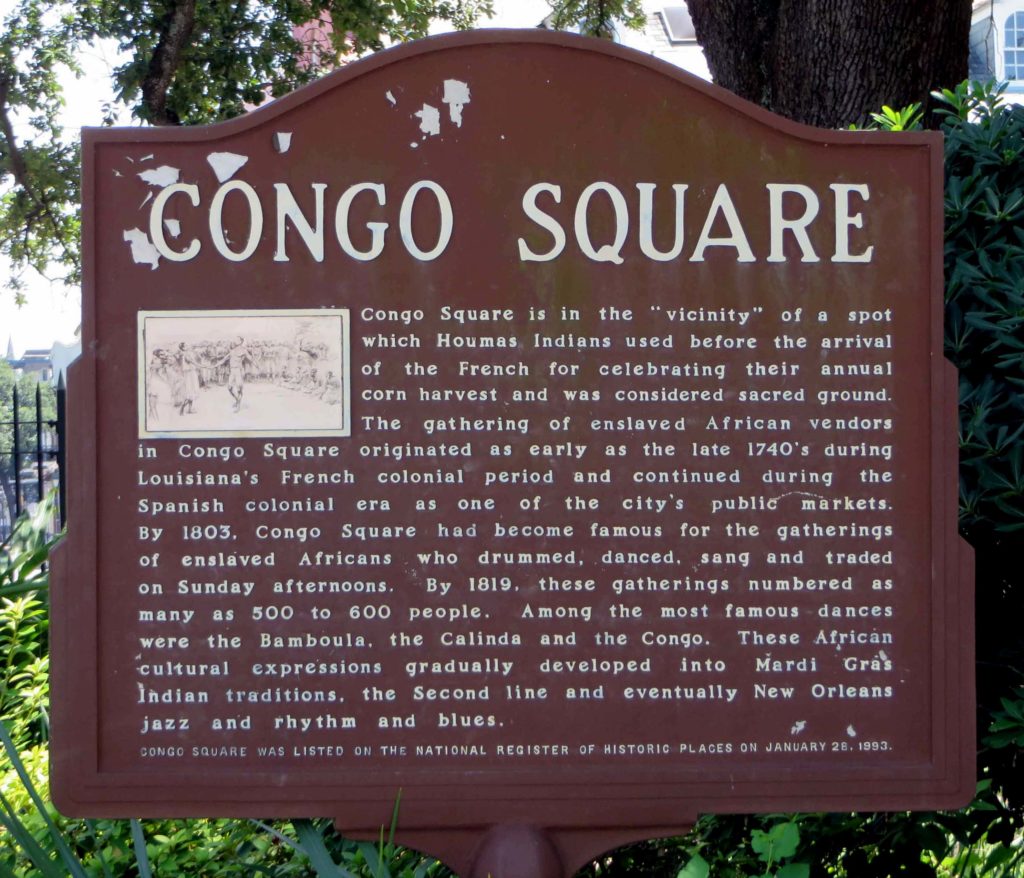

Those rhythms and blues later became fundamental in the early development of yet another popular musical form: rock and roll. In retrospect, writers continue to disagree on the exact origins of what became rock music; however, New Orleans looms large in nearly every interpretation. For his part, Elvis Presley famously insisted in 1956 that New Orleans’ own Fats Domino was “the real king of rock and roll” (see Figure 1). Many writers now look back on Domino’s “The Fat Man,” recorded in 1949, along with Roy Brown’s “Good Rocking Tonight” (1947) and Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti” (1955), as preeminent contenders for the first unequivocally rock and roll track. Amazingly, each of those records were among the many milestone works recorded and engineered at Cosimo Matassa’s legendary J&M Recording Studio (see Figure 2). Backed by versatile bandleader Dave Bartholomew and drummer Earl Palmer—an early and prolific progenitor of rock and roll’s signature backbeat, the likes of Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Dr. John, Jerry Lee Lewis, Professor Longhair, Irma Thomas, and Allen Toussaint all cut sides with Matassa at J&M. Housed in his father’s appliance store at the corner of Rampart and Dumaine Streets, J&M sat just one block down from the site now commemorating Congo Square. In 2010, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame designated the studio one of just eleven nationwide Historic Rock and Roll Landmarks.[iv]

Before co-founding the influential groups the Meters and the Neville Brothers, Art Neville began his recording career at J&M, laying down “Mardi Gras Mambo” with the Hawketts in 1954. The Carnival classic celebrates New Orleans’ enduring camaraderie with the Caribbean and remains a popular seasonal standard. A decade later Neville helped form The Meters, a powerhouse electric rhythm section that drew on syncopated second line rhythms and call-and-response Mardi Gras Indian chants to become an early architect of the style later known as funk (see Figure 2). The Meters became a sturdy foundation of the mid-century New Orleans sound, serving as the house band for Allen Toussaint’s Sansu label and backing renowned New Orleans soul and R&B artists Lee Dorsey, Irma Thomas, and Dr. John, among many others. As independent recording artists the band released several hits that remain New Orleans classics, including Hey Pocky Way, based on Mardi Gras Indian chants, and Cissy Strut, a gritty funk standard now considered an early milestone in the genre.[v]

The street culture of Mardi Gras Indians came of age with the city’s popular music, from second line to jazz to R&B to funk. Jelly Roll Morton discussed Indian culture with Alan Lomax at the Library of Congress in 1938, even rapping the traditional patois chant “T’ouwais, bas q’ouwais [tu es pas coller or two way pocky way]” on which the Meters based their mid-century hit. Later groups of Mardi Gras Indians combined their oral traditions with syncopated electric funk to create a popular and enduring sub-genre. A group led by big chiefs Bo Dollis and Monk Boudreaux joined bandleader Willie Tee and blues guitarist Snooks Eaglin to record as the Wild Magnolias in 1970 (see Figure 3). Now an acclaimed New Orleans institution, the Wild Mags continue to perform both as a traditional Indian gang and a funk band on the streets and in venues throughout the city.[vi]

The musical origins of the Neville Brothers lie also in Mardi Gras Indian traditions, leaning on their Uncle Jolly (George Landry), a big chief with the Wild Tchoupitoulas tribe, for musical inspiration and connections. Backing Landry, the four Neville Brothers – Art, Aaron, Charles, and Cyril – joined forces with the Meters in 1976 to cut Wild Tchoupitoulas, produced by Allen Toussaint. That record drew heavily on Mari Gras Indian chants, traditions, and performance, and foreshadowed the rise of the Neville Brothers as a national supergroup. Many Indian groups such as Big Chief Juan Pardo and the Golden Comanche and the 79ers Gang continue to record and perform the Indians’ rhythms and rituals, often emphasizing their profound connections to the Black Atlantic. International hits based on Indian compositions and traditions such as Iko Iko, Handa Wanda, Hey Pocky Way, and Earl King’s Big Chief remain revered New Orleans standards.[vii]

As New Orleans rhythm and blues morphed into rock and roll and later funk, other influential offshoots were materializing in the city, elevating two queens to global eminence. “New Orleans Soul Queen” Irma Thomas recorded many of her early soul classics at J&M, and continues to perform as a leading figure in the genre. Civil Rights activist and icon Mahalia Jackson got her start singing in the full gospel congregations of Plymouth Rock and Mount Moriah Baptist Churches in Uptown New Orleans (see Figure 4). From there she went on to inspire millions as the “Queen of Gospel,” combining the soulful Black spirituals of the plantation South with syncopated rhythms she learned to tap out on the wood floors of her New Orleans churches.[viii]

In both the background and the forefront of the rich diversity and complexity of twentieth century New Orleans music, piano players remained iconic. There is perhaps no better single example of the multiplicity and centrality of piano players in the city than the irrepressible Mac Rebennack, known worldwide as Dr. John. A celebrated composer and performer from the 1950s to the present, Dr. John remains distinguished as a standard bearer and keeper of the flame for the storied New Orleans piano professor tradition. As a teenager Dr. John drew early inspiration from Fats Domino, Little Richard, and especially Professor Longhair in the clubs and studios around town. His range as a player, however, transcends R&B to traverse a wide array of styles including rock, jazz, funk, and the haunting voodoo-inspired psychedelia for which he became most distinctive.[ix]

After trouble found him in New Orleans, Mac fled to Los Angeles where the libertine spirit of late-60s California gave him license to experiment with New Orleans music in new and profound ways. There Mac serendipitously came under the wing of New Orleans patriarch Harold Battiste who managed to finagle some free studio time between Sonny and Cher takes in 1967. The duo put together a group of veteran New Orleans musicians to explore a visionary musical concept and stage persona based on nineteenth-century voodoo conjurer and man about town, Dr. John Montaigne (or Jean Montanet). A formerly enslaved native of Senegal, Dr. John the elder regained his freedom in Cuba before rising to prominence as a trusted root doctor in antebellum New Orleans. His 1885 obituary in Harper’s Weekly deemed him “the last of the Voudoos,” that is “the last really important figure of a long line of wizards or witches whose African titles were recognized,” and “the most extraordinary African character that ever obtained celebrity” in New Orleans. Studying the legend of Dr. John, Mac discovered a reference to one Pauline Rebennack, arrested along with Montaigne in the 1840s for her involvement in voodoo and other illicit acts. Realizing a likely familial connection, Mac assumed the stage persona Dr. John the Night Tripper, and with fellow New Orleans musicians in exile cut the classic LP Gris-Gris. That album amounted to a profoundly New Orleanian tribute to the Black Atlantic, melding the syncopated rhythms and bamboula dances of Congo Square with the power and grace of Afro-Caribbean spirituality and the lavish costumes, chants, and performance art of the Mardi Gras Indians. The result was a fantastic if somewhat cryptic masterpiece that conjured a range of New Orleans traditions to stake out the eeriest edges of the psychedelic zeitgeist of the 1960s.[x]

After beginning his career as a guitar player and session musician for J&M, a gunshot to the finger forced Dr. John to switch to the piano. His teacher was the brilliant and irrepressible James Booker, whom Mac later called “the best black, gay, one-eyed junkie piano genius New Orleans has ever produced.” Judging from the testimonies of his peers and scattered live recordings Booker left behind, it is clear that he was among the most talented and original piano players the city ever gave us, notwithstanding Dr. John’s tongue-in-cheek qualifiers. Booker was an undisputed piano genius who brought classical heft to New Orleans rhythm and blues while sacrificing none of its soul. Booker could play it all: R&B, jazz, rock, classical, soul, gospel—often in a single performance, while making it feel deliberate and cohesive. In a town distinguished by a long and storied history of world-class piano players, Booker may have been its most versatile and proficient. Tormented by addiction and inner turmoil, the tragic genius and epicure died in the waiting room of Charity Hospital in 1983, far before his time.[xi]

Note: Click at your own risk! The links in the following section contain content some may consider not safe for work (NSFW).

New Orleans’ elaborate musical traditions allow the city’s art to interact with more broadly popular forms in exciting ways. Beginning in the mid 1980s, for instance, bounce arose as a distinctive form of hip hop in New Orleans before eventually gaining international renown. In bounce, typically flashy performers belt out persistent, call-and-response lyrics over hard-charging, circular beats to create a high-energy electronic dance music and a vibrant cultural scene. Performers DJ Jubilee, Ms. Tee, Cheeky Blakk, and Magnolia Shorty came to prominence in the early scene with hyper-sexualized lyrics and teams of flamboyant twerk dancers. Today queer performance artists such as Katy Red, Big Freedia, and Sissy Nobby enjoy international acclaim, and the genre appears poised for an explosion. Notable New Orleans hip hop artists Lil’ Wayne, the Hot Boys, Mannie Fresh, and the Cash Money record label all got their start in bounce, before pushing its boundaries and climbing the charts in mainstream hip hop.[xii]

Bounce and related forms of New Orleans hip hop arose from roots in the city’s public housing developments, especially the (former) Calliope and Magnolia projects. No Limit brothers Master P, Silkk the Shocker, and C Murder grew up in the former, while Juvenile, Soulja Slim, and “the queen of bounce” Magnolia Shorty, all hail from the latter. Before its demolition and redevelopment in 2014, the Magnolia projects were an important cultural crossroads in the city. Its A.L. Davis Park (formerly known as Shakespeare Park) has served as a historic training ground for second lines and brass bands, and remains an important gathering site for Mardi Gras Indians on Super Sunday. Just across LaSalle Street sits the Dew Drop Inn, a legendary lounge, barbershop, restaurant, hotel, and 24-hour performance venue that hosted a who’s who of soul and R&B acts, including Roy Brown, Dave Bartholomew, Fats Domino, Ray Charles, James Brown, Otis Redding, Little Richard, and so many others in the 1950s and 60s (see Figure 5). The club was a cornerstone of African American society in mid-century New Orleans, serving as a laboratory where late night sonic experiments led to early advances in rhythm and blues and rock and roll.[xiii]

In the twenty-first century, as New Orleans continues to innovate new musical forms and styles, the city remains devoted to jazz—its first born. The Preservation Hall Jazz Band and other acts based in traditional jazz sounds continue to pack venues in New Orleans and worldwide. So, too, have the Blues continued to travel down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, at times in the form of legendary artists such as Little Freddie King or turning up in distinctive local interpretations like the mystical Acadiana blues of the late Coco Robicheaux. New Orleans R&B Emperor Ernie K-Doe kept the mid-century sound alive with regular performances (musical and otherwise) in his storied Tremé nightclub, The Mother-in-Law Lounge, until his death in 2001. Shuttered in 2010, the New Orleans institution reopened a year later thanks to the efforts of beloved New Orleans trumpeter and bon vivant Kermit Ruffins.

New Orleans royal families such as the Andrews, the Battistes, and the Marsalises continue to rear and train world-class musicians in the jazz and rhythm and blues traditions. Harold Battiste founded the collective A.F.O. (All For One) Records in 1961, the city’s first label owned and operated by African-American musicians. Before his death in 2015, he had educated hundreds of New Orleans musicians in New Orleans as a public school teacher and later on the faculty in the jazz studies program at the University of New Orleans. There he mentored an impressive list of twenty-first-century jazz luminaries, including Wynton and Branford Marsalis, saxophonist Donald Harrison Jr., trumpeters Nicholas Payton and Terence Blanchard, and pianist Jesse McBride. Hailing from the storied Tremé neighborhood, the Andrews family blurs the boundaries that would otherwise delineate styles of New Orleans music. Cousins James, Glen David, and Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews carry on the traditional sounds of the city from second line to jazz to funk.

Jazz saxophonist Donald Harrison Jr. demonstrates both the diversity and complementarity of New Orleans music by interweaving many of the city’s most celebrated styles. Backed by his father—the late Big Chief Donald Harrison Sr.—and Dr. John, Harrison seamlessly melds Mardi Gras Indian chants and percussion with his free flowing, post-bop jazz and Dr. John’s barrelhouse piano on the 1992 Indian Blues. With his Spirits of Congo Square, Harrison presents the collective roots of New Orleans music in the legacies of Congo Square.

In the activist spirit of Mahalia Jackson, Harrison’s nephew Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah “stretches” traditional jazz with hip hop samples and second line rhythms designed to highlight contemporary anti-racist social movements. Local jazz aficionado Irvin Mayfield leads a renowned Latin Jazz group with percussionist Bill Summers. Their Grammy-winning Los Hombres Calientes reaffirms New Orleans’ enduring musical connections to Latin America and the Caribbean. The emerging Tank and the Bangas are among the most exciting groups in New Orleans today. Combing New Orleans jazz, funk, and hip hop with a charismatic slam poetry sensibility, Tank demonstrates, once again, the limitless potential and broad appeal of New Orleans music.

While jazz continues to diversify in infinite directions, brass bands remain essential cultural and economic institutions in the city. Groups such as the Dirty Dozen, the Hot 8, Rebirth, the Soul Rebels, Tremé, and Soul Brass Band perpetually update the tradition with new styles and sounds while maintaining their fundamental connections to the earliest forms of jazz. On any given day in New Orleans, countless brass bands second line through the city’s streets, animating onlookers with a “big noise” that recalls Buddy Bolden at the turn of the twentieth century.

In the twelve or so decades following the birth of jazz, a delightful multiplicity of styles and sounds emerged in New Orleans. Despite the ever-expanding diversity and complexity of the city’s music, each of its magnificent innovations emerges from roots in the bedrock of syncopated rhythms and call-and-response lyrical forms given life at Congo Square. Fortunately for us, the essence of Congo Square beats on in two important commemorative spaces: its somber historic landmark in Louis Armstrong Park and as a dedicated stage at the annual New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival (see Figure 6). On that stage, when Donald Harrison, Jr., masks in Indian regalia to lead his swinging jazz band over syncopated rhythms, and when Big Freedia directs her twerk team with call-and-response lyrics, they all stir a heaping pot of gumbo that first felt the flame in Place Congo, at the back of town, in New Orleans.

To prepare for your trip to the Crescent City, keep the Guardians of the Groove, New Orleans community radio WWOZ streaming in the background at all times. Take an open online course on New Orleans music from Dr. Matt Sakakeeny, Assistant Professor of Music at Tulane University. Listen to an archive of Mardi Gras Indian performances from 1985 and a more recent writeup hosted by Smithsonian Folkways Magazine. Watch a YouTube playlist of recordings of Mardi Gras Indians compiled by the Alan Lomax archive and a mishmash YouTube playlist curated by the author. Once again, I cannot recommend enough A Closer Walk, an interactive website, map, and series of guided tours of the geographies of New Orleans music, sponsored by WWOZ and others. In the city, visit the Louisiana Music Factory to purchase hard-to-find vinyl, CDs, films, etc. Check out the WWOZ Live Wire page for the most comprehensive listings for live music in the city, and then go find some.

— Case Watkins, James Madison University

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0029

[i] Grace Lichtenstein and Laura Dankner, Musical Gumbo: The Music of New Orleans (New York: W.W. Norton, 1993); Jason Berry, Jonathan Foose, and Tad Jones. Up from the Cradle of Jazz: New Orleans Music Since World War II, revised ed. (Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2009).

[ii] Al Rose, Storyville, New Orleans: Being an Authentic, Illustrated Account of the Notorious Red-Light District (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1974); Lichtenstein and Dankner, Musical Gumbo. See also Part 1 of this essay for more on Storyville and the emergence of Jazz.

[iii] Quotes in Ferdinand “Jelly Roll” Morton, Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings by Alan Lomax, Music CD (Cambridge, MA: Rounder Records, 2005): Disc 6, Tracks 8 and 9. Lichtenstein and Dankner, Musical Gumbo; Robert Palmer, “Folk, Popular, Jazz, and Classical Elements in New Orleans,” in Folk Music and Modern Sound, ed. William Ferris and Mary L. Hart (Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2008), 194-201.

[iv] John Broven, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans (Gretna, LA: Pelican, 1988); Rick Coleman, Blue Monday: Fats Domino and the Lost Dawn of Rock “n” Roll (Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2006: p. 246); Jim Cogan and William Clark, Temples of Sound: Inside the Great Recording Studios (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2003)

[v] John Storm Roberts, The Latin Tínge: The Impact of Latin American Music on the United States (New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979); Alexander Stewart, “New Orleans, James Brown and the Rhythmic Transformation of American Popular Music,” Popular Music 19, no. 3 (2000): 293-318; Ned Sublette, The World That Made New Orleans: From Spanish Silver to Congo Square (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2008). Ned Sublette, Cuba and Its Music: From the First Drums to the Mambo (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2004).

[vi] Alan Lomax. Mister Jelly Roll (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1950); Berry et al. Up from the Cradle of Jazz.

[vii] Lomax. Mister Jelly Roll; Berry et al. Up from the Cradle of Jazz; David Ritz, Charles Neville, Aaron Neville, and Cyril Neville. The Brothers: An Autobiography (New York: Da Capo Press, 2001).

[viii] Berry et al. Up from the Cradle of Jazz; Jules Victor Schwerin. Got to Tell It: Mahalia Jackson, Queen of Gospel (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

[ix] Dr. John (Mac Rebennack) with Jack Rummel. Under a Hoodoo Moon: The Life of the Night Tripper (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1995).

[x] Quotes in Lafcadio Hearn. “The Last of the Voodoos,” Harper’s Weekly 29 (Nov. 7, 1885): 726–27, reprinted in S. Frederick Starr, ed. Inventing New Orleans: Writings of Lafcadio Hearn (Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, 2001): 77-82; Dr. John, Under a Hoodoo Moon.

[xi] Quote aired in Lily Keber, Bayou Maharajah: The Tragic Genius of James Booker (Film: Mairzy Doats Productions, 2016), available on Netflix. Trailer available on Vimeo.

[xii] Matt Miller, Bounce: Rap Music and Local Identity in New Orleans (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012); Afropop Worldwide, “Shake It Fo Ya Hood: Bounce, New Orleans Hip-Hop,” (podcast, 2017).

[xiii] Berry et al. Up from the Cradle of Jazz; Coleman, Blue Monday. An illuminative and disturbing documentary (NSFW) of C Murder and the Calliope projects is available here. Super Sunday is a gathering of Indians typically held on the Sunday nearest St. Joseph’s Day. The Calliope and Magnolia are two of the four public housing developments that city and federal authorities demolished and redeveloped following Katrina.