The Geography of Despair (or All These Rubber Bullets)

Aretina R. Hamilton

Aretina R. Hamilton

This article was originally published on Medium. Follow Dr. Hamilton on Twitter at @BlackGeographer.

As a scholar, I entered the world of academia as a planner. I examined urban planning and the devolution of American cities — and then I discovered Geography. The original scene of the crime. This original technology was used to cut up the world into pieces and to fulfill manifest destinies. When non-Geographers think about Geography, they imagine GPS maps, landscapes, physical terrain, and valleys. They don’t think of culture, people, conflict, contestation, imperialism, or exploitation. In the same way, geographical thinking frequently ignores how geographies enact violence, create spaces of belonging, reproduce systematic equalities, and codify race. Yet for Black People, geography operates across multiple sites and multiple planes, and it is all-encompassing, frequently defining the outcomes of our lives.

My first site of geographic containment occurred within the walls of my mother’s uterus. It was a site of warmth, love, and nourishment. Even before I sprang into the world, I could feel the yearning for me and the love of my parents as they spoke to me. As a Black child growing up in Louisville, Kentucky in the 1980s, I began to understand that my geographies were filled with visceral meanings and assumptions. At my elementary school, I attended one of the most racially and socioeconomically diverse schools in the city. We were a fulfillment of the dream. However, as I grew older and reflected back on those times, I remember how the Black kids who lived in Southwick, Parkhill, and the West End were disproportionately called out for behavioral or socio-emotional issues. They lived in spaces that lie along the margins of the map, sites on “the other side of the tracks,” and there was a definite difference in how they were treated. At that age, we never discussed where we came from, but we knew that geography had a dramatic impact on where we might end.

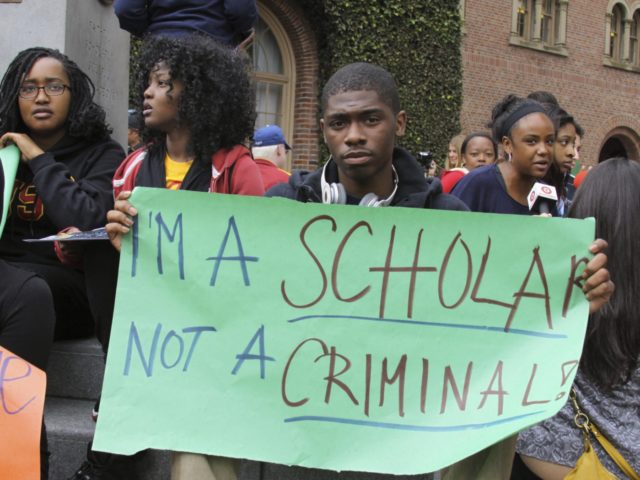

As a Black Geographer who understands how race takes place, it is impossible for me to not view these crucial moments — the protests, anti-colonial movements, and rage — in isolation. They are all interwoven into my fabric. If I occupied different geography (birth, neighborhood, city), any of these deaths might have befallen me. As most Black folks are aware, no amount of degrees, money, or social class will protect you. Even as I try to look for glimmers of hope, I am, in the words of Dr. Robert Sellers at the University of Michigan, “ bone-weary tired.”

Over the past 72 hours, I have watched social media, news, and reports on TV as atrocious things were done to protestors who were merely exercising their rights as citizens.

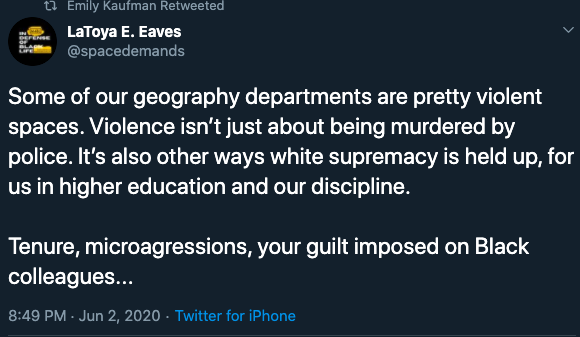

It is a harrowing enterprise that few of my white colleagues will ever understand, even as they lament the injustices — it is clear that a cognitive dissonance occurs. While I am distraught and heartbroken by the thousands upon thousands of Black bodies and others who are being shot down by the military-industrial complex, I find myself experiencing an extensional crisis as I consider the frequent violence that has been cast upon Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in the academy, in graduate school, and yes, in our professional organizations. This violence is often invisible and difficult to comprehend. It may not cause bloodshed or impede your physical mobility. There are no batons or angry, fear-mongering cops with knees on your neck. And yet it is palpable. We feel the pain. It never ceases. It remains contained in our bodies, violently thrashing.

The violence occurs as you attend academic conferences even as you are relegated to the margins — unless it’s a popular topic that can be marketed and commodified. The violence occurs as you watch your white classmates and professors walk past you — erase you from memory even as they brag about the growth of diversity in the department. The violence occurs as you watch your white colleagues climb in their station on the backs, social proximity, and scholarship of Black folks whom they claim to respect; even as they only acknowledge you when it’s convenient or professionally advantageous. The violence falls upon your body like rubber bullets as you listen to them lament about the desire to “do more to ensure that [any subject] as a discipline becomes inclusive and equitable,” even as there remain a paucity of positions, postdocs and Black tenured faculty in those areas.

We are hemorrhaging — as we feel the blow and impact on our souls.

On June 1, 2020, the largest national professional organization of geographers, the American Association of Geographers (AAG), released a statement regarding the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery. Like many other organizations, the AAG released a neatly packaged statement condemning the violence of these acts of racist violence while recognizing its own growing edges.

AAG recognizes that it must do more to ensure that geography as a discipline becomes inclusive and equitable. Geographers have long been at the forefront of scholarship on the social and spatial foundations and consequences of racism, violence, and inequality. But this is not enough. We need to use our research, our teaching, our mentorship, our work, and our science to stand up against systemic inequality. Source link.

As I read the statement, I thought about the numerous sessions I chaired during the annual Meetings of the AAG where scholars of Color talked and sometimes whispered about the trauma that occurred in their departments. I thought about the Black, Indigenous, and People of Color Geographers who write about racism, inequality, and violence and how these same scholars have reinvigorated and conducted vital research and praxis on environmental racism, southern geographies, LGBTQ sites of exclusion, radical Black Power Movements, Black food Geographies, blues epistemologies, the prison industrial complex, racial conflict, community building, police brutality, and the racial politics of citizenship and migration. This list is not exhaustive. And yet while the organization was right to call out the violence in the streets, I wondered when we might turn the gaze inward.

Despite our understanding of colonial thought and power, geographers — like many other scholars — are less willing to look inward. We speak in platitudes and identify oppression as placeless, when the place is here and now. The colonial space of the academy has never truly been exposed. Instead, we point and judge and critique — ignoring the ways that all the Black, Brown etc. people sit next to each other in the sessions, in classes, in working groups. We see you.

Six months before I received my Ph.D., my father passed away. I could not grieve. I had killed those parts of me a long time ago. So like a drone, I delivered his eulogy, buried him, and went back to my work. I was a prisoner. And when I finished my degree, I had no energy to enter into a job or to pursue a traditional academic career. I was broken. I was tired.

Even as some geographers unpack the systemic inequality and violence initiated by the state, they remain blind to the violence they perpetuate daily within classrooms, research settings, advising and mentoring, conferences, publishing venues, professional organizations, career networks, job searches, and tenure and promotion decisions. So while they may condemn the theatres of violence playing out at this historical moment, it is not just a moment for me and others like me. In the words of Dr. Harold Rose, the first and only Black president of the AAG, the overwhelming despair we feel right now is not just a moment. It is built into the very fabric of African African life:

“It would have been more pleasant to have reported on a topic that reflects the geography of happiness…[but] my geography was the geography of despair”. ~Dr. Harold Rose, 1978 American Association of Geographers Presidential Address

Dr. Aretina Rochelle Hamilton is a cultural geographer whose areas of specialization include Black Geographies, Black Queer Cartographies, and Racialized Space and Trauma. Dr. Hamilton received her doctoral degree in Geography from the University of Kentucky. She was recently appointed as the inaugural Associate Director, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at the Interlochen Center for the Arts. You can follow her on Twitter @BlackGeographer.

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0076