American Indians of Washington, D.C., and the Chesapeake

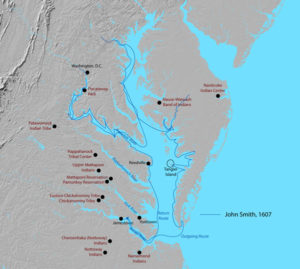

When Captain John Smith sailed up the Potomac River in 1608, he found 13 American Indian villages along its banks. Spanish incursions beginning in 1521 brought diseases, land grabs, resource destruction, military assaults, and slave raids. Nonetheless, there were several large villages and fortified towns by the time of John Smith’s 1608 visit. At that time, three major political groups vied for power in the region: the Susquehannock in Pennsylvania; the Piscataway Chiefdom in southern Maryland; and the Powhatan Chiefdom in Virginia and farther south.

When Captain John Smith sailed up the Potomac River in 1608, he found 13 American Indian villages along its banks. Spanish incursions beginning in 1521 brought diseases, land grabs, resource destruction, military assaults, and slave raids. Nonetheless, there were several large villages and fortified towns by the time of John Smith’s 1608 visit. At that time, three major political groups vied for power in the region: the Susquehannock in Pennsylvania; the Piscataway Chiefdom in southern Maryland; and the Powhatan Chiefdom in Virginia and farther south.

Every place in the Western Hemisphere has an ongoing American Indian story, and the Washington, D.C., area is no exception. People had settled on the shores of Washington’s Anacostia and Potomac rivers as early as 9,500 BCE. Their descendants still reside here. The Nacotchtank Indians of what is now D.C. were part of the Piscataway Chiefdom, with settlements stretching along the Potomac River. Anacostia, a rendering of the word “Nacotchtank” by the English Jesuits who came with Leonard Calvert in 1634, was the home of their most important leader.

Indians of the Chesapeake Bay would form early and lasting impressions on the newly-arriving European settlers. This is where Pocahontas met Captain John Smith, after all, setting up one of the great legends of early American settlement. But the presence of Indians also played a role in racial segregation laws that were only recently changed.

Chesapeake Indians were riverine communities, drawing sustenance from the waterways for as much as 10 months of the year. The Powhatan confederacy of Indians that greeted the Jamestown settlers included tribes from the Carolinas to Maryland. The Piscataway often sided with the Powhatan Chiefdom against the English, and when the Powhatan were defeated in 1646, English settlements quickly expanded. King Charles deeded Piscataway territories to Lord Baltimore in 1632, and European settlements reached what is now Washington, D.C., by 1675.

British settlement during the 17th century followed the usual pattern of expansion. Indians were pushed off their lands. Treaties and alliances were made, then promises broken. Frontiersman pushed into Indian land at the expense of the communities. Epidemics of introduced diseases decimated the Indigenous population, down to perhaps a tenth of its former number.

“There is petition after petition, speech after speech, on record by the chiefs to Maryland Council, asking them to respect treaty rights,” says Gabrielle Tayac, niece of Piscataway Chief Billy Tayac. “Treaty rights were being ignored, and the Indians were getting physically harassed. The first moved over to Virginia, then signed an agreement to move up to join the Haudenosaunee [Iroquoise Confederacy]. They had moved there by 1710. But a conglomeration stayed in the traditional area, around St. Ignacious Church. They’ve been centered there since 1710. Families mostly still live within the old reservation boundaries.”

“By 1700, the English had settled and established plantation economies along the waterways, because they are shipping to England,” says anthropologist Danielle Moretti-Langholtz at the College of William and Mary. “Claiming those pathways pushed the Indians back, and the back-country Indians become more prominent. Some Natives were removed and sold into slavery in the Caribbean. This whole area was kind of cleaned out. But there are some Indians that remain, and they are right in the face of the English colonies. We can celebrate the fact that they’ve held on.”

But it was racial laws and policies that pushed for the near “disappearance” of Indians from the region. In Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676, white indentured servants united with black slaves in an uprising against the Virginia governor in an attempt to drive Indians out of Virginia. They attacked the friendly Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes, driving them and their queen Cockacoeske into a swamp. Bacon’s Rebellion is said to have led to the Virginia Slave Codes of 1705, which effectively embedded white supremacy into law, driving a wedge between whites and blacks that came to dominate American social dynamics.

Perhaps most damaging of all was the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, pushed forward by the white supremacist and eugenicist Walter Ashby Plecker, the first registrar of Virginia’s Bureau of Vital Statistics. This Act made it unsafe—and, in fact, illegal—to be Indian. Plecker decreed that Virginia Indians had so intermarried—mostly with blacks—that they no longer existed. He instructed registrars around the state to go through birth certificates and to cross out “Indian” and write in “Colored.” Further, the law also expanded Virginia’s ban on interracial marriage.

While many Indians simply left, the Mattaponi and Pamukey stayed isolated, which protected them. They kept mostly to themselves, not even connecting with the other Virginia tribes. But they continue today to honor their 340-year-old treaty with the Governor of Virginia by bringing tribute every year.

On the Eastern side of the Chesapeake Bay, the Nanticoke mostly fled into Delaware, while a small band called the Nause-Waiwash moved into the waters of the Blackwater Marsh. “We settled on every lump,” said the late chief Sewell Fitzhugh. “Well, a lump is just a piece of land that is higher, that doesn’t flood most of the time.”

The remnant Maryland tribes consolidated under the name of Piscataways, and around 1700 removed to southern Pennsylvania. There they came under the protection of the Iroquois, where they became known as the Conoy. By the end of the 18th century their official numbers had been reduced to 320 persons. Their lands and political autonomy were completely destabilized, and reservation boundaries were not respected past 1700.

Virginia’s ban on interracial marriage would not be overturned until 1967, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia. Mildred Loving is often identified as black. She was also Rappahannock Indian. But consequent to Plecker’s actions, Virginia Indians faced considerable challenges proving their unbroken lineage—a requirement necessary for achieving status as a Federally Recognized Tribe. The Pamunkey received Federal recognition in 2015, and six other Virginia tribes in January 2018—500 years after Pocahontas.

The Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian located on the National Mall, welcomes you to visit and learn more about the Piscataway and other Indigenous peoples of the Americas during your visit to Washington, D.C., for the 2019 AAG Annual Meeting.

Recommended readings:

The Aborigines of the District of Columbia and the Lower Potomac – A Symposium, under the Direction of the Vice President of Section D. Otis T. Mason; W J McGee; Thomas Wilson; S. V. Proudfit; W. H. Holmes; Elmer R. Reynolds; James Mooney. American Anthropologist, Vol. 2, No. 3. (Jul., 1889), pp. 225-268. https://www.jstor.org/stable/658373?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Joe Heim, 2015. “How a long-dead white supremacist still threatens the future of Virginia’s Indian tribes.” Washington Post, July 1, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/how-a-long-dead-white-supremacist-still-threatens-the-future-of-virginias-indian-tribes/2015/06/30/81be95f8-0fa4-11e5-adec-e82f8395c032_story.html?utm_term=.dc92b208fd4f

WE HAVE A STORY TO TELL: The Native Peoples of the Chesapeake Region. Teacher Resource, National Museum of the American Indian, 2006. https://nmai.si.edu/sites/1/files/pdf/education/chesapeake.pdf.

John Smith’s Chesapeake Voyages, 1607-1609. Helen C. Rountree, University of Virginia Press, 2008.

DOI: 10.14433/2017.0038