A Taste of New Deal Alphabet Soup in San Francisco

Coming to San Francisco for the annual meeting next spring will mean inevitably traversing a landscape transformed by the New Deal. For those landing at the San Francisco or Oakland Airports, The Works Progress Administration (WPA), Public Works Administration (PWA), and State Emergency Relief Administration (SERA) all had a hand in their growth into major airports. Crossing over the majestic western span of the Bay Bridge is to rely on the New Deal as well. In 1936 when it was completed at the hands of the WPA, the bridge was the longest suspension bridge in the country. From the bridge, many visitors quickly pick out one of the city’s most visible landmarks, Coit Tower, where the entire interior is covered in New Deal frescos. With funds from the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), the New Deal’s first public arts program, twenty-six artists spent six months in 1934 creating murals of depression era life and the state’s history. The murals were carefully restored last year and are once again on view to the public as a monument not just to California but a historical moment when the federal government invested directly in the arts, infrastructure and its poorest citizens.

Pieces of San Francisco’s history, like that of Coit Tower, are relatively well known. But the extent of the structural and aesthetic improvements made to the city are just now being recovered by a team of researchers and volunteers at the Living New Deal project. Founded and directed by Berkeley Geographers Richard Walker and Gray Brechin (a longer history of the project is available on our website), the Living New Deal works to rediscover, catalog and map the sites of New Deal art and infrastructure. To many people’s surprise, there are no complete records of New Deal programs; this in part because of their emphasis on ending the Depression as quickly as possible, and in part because of long standing efforts to obscure the New Deal’s success in doing just that. Given the enormity of its scope, over the last decade the Living New Deal has grown into a national collaboration of geographers, researchers from disciplines ranging from art history to economics, students, many amateur historians and untold numbers of volunteers submitting information on what the “alphabet soup” of programs created in their regions. In the same spirit of serving the public good that defined the original New Deal, our group works to make all of the information gathered for our database and map freely available via the web, publications and frequent presentations around the country.

The Living New Deal’s origins in the Bay Area are reflected in the density of New Deal sites already uncovered in and around San Francisco. Those first years of research revealed that no corner of the city was left untouched by WPA, PWA, CWA, CCC or one of the other agencies. As shown on the project’s map, the city is literally dotted with parks, playgrounds, schools and public buildings, street and sewer improvements, murals, sculptures, and other works of art. Neighborhoods famous for other reasons turn up New Deal touches everywhere. A walk through the Castro includes sidewalks still stamped with WPA logos. Chinatown’s St. Marys square is home to a 14-foot tall statue of Sun Yat-Sen by the renowned sculptor Beniamino Bufano, paid for by the Federal Arts Project (FAP). Golden Gate Park is chock full of New Deal improvements that endless hippies, yuppies, and tourists have made use of for nearly eight decades without ever likely considering their origins. Federal funds flowed far beyond just the major cities however, even to Republican led communities like Berkeley (yes, it was a different place in the 1930s), where civic structures like the high school and post office are adorned with art extolling the public value of knowledge and beauty. Just slightly further afield are trails and open spaces made possible by the work of the Civilian Conservation Core (CCC), meant to provide even the most destitute Americans access to the therapeutic dimensions of the “great outdoors.” Of course many of those spaces are still readily accessible to us today. The list of New Deal sites that we take advantage of in the 21st century goes on and on, and grows with every passing week of new discoveries.

While the Living New Deal works to reveal and promote the legacy of work in the name of the public good, the archive and map make apparent that this legacy is in no way free of the problematic politics and mainstream thought of the time from which it emerged. From environmental destruction (note how much “reclaimed” land the airport occupies), to the racist representations and exclusions of indigenous peoples in art celebrating California’s colonial history, to the complicated first “progressive” efforts at public housing (coupled with policies that underwrote the mass suburbanization of whites), the Bay Area contains it all.

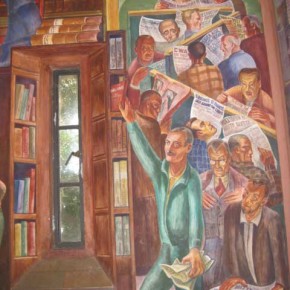

In juxtaposition to the relics we find abhorrent in the present, the city also contains projects so radical that they have been raising the ire of civic leaders and the “business community,” for decades; probably none more so than the murals at the Rincon Annex. Created by Russian born artist Anton Refregier, who “wanted to paint the past, not as a romantic backdrop, but as part of the living present, a present shaped by the trauma of depression, strikes, and impending war” (Brechin, 2013), the murals adorn the interior of a beautiful post-office building. The works themselves, however, depict a much more violent history underlying San Francisco’s history, beginning with Sir Francis Drake holding a bloodied sword (his hand infamously reappears emerging from a Nazi flag in a later panel, connecting the original conquest to the rise of Fascism), the murals continue on to show a much “truer” depiction of the Mission system, the beating of Chinese during anti-immigrant riots, the murder of striking workers, and the general hardship that befell many of San Francisco’s pre-war inhabitants. Despite many efforts to stop the murals from being produced in the first place and censorship, they are still on display at the building and open to the public—just a few blocks from the Ferry Building.

For those who will be at the conference, several current and former team members from the project will be on hand and always excited to discuss the New Deal. For those who would like to explore New Deal sites on their own, this is San Francisco, so there is of course “an app for that.” Local public media network KQED worked with the Living New Deal and California Historical Society to create an iPhone and Android app called “Let’s Get Lost,” which features interactive tours of both Coit Tower and Rincon Annex Murals. Or, for the adventurous geographers looking to get out and explore, an actual print map of a self-guided tour of New Deal sites in San Francisco is available.

Geographers who won’t be attending the meeting are still able to explore the legacies of the New Deal in their own regions via the project’s website and interactive map. The Living New Deal has just begun to scratch the surface of what was created by the alphabet soup of federal projects, and strongly encourages interested persons with knowledge of unlisted or incomplete entries for their area to be in touch! Whether in the Bay, another town, or the vast rural and wilderness spaces of the US, the Living New Deal hopes our project will encourage our fellow geographers to look for clues to how the New Deal continues to shape not just the history of the country but the places we inhabit every day.

Alex Tarr is the former project manager at the Living New Deal project and currently the Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Spatial Humanities at the Rice University Humanities Research Center. He received his PhD in geography from the University of California, Berkeley in 2015. A more complete list of the many geographers who have contributed to the Living New Deal is available on the website.