A Movement Lab in New Orleans

The evening of Wednesday, May 20, was a night like any other in a town that, despite its near-demise a decade ago, persists as this country’s beating heart of creative chaos. By 6:30, the bars on Frenchmen Street were clinking to life. Around the city, Walter “Wolfman” Washington, the TBC Brass Band, and Delfeayo Marsalis were among the world-class musicians preparing for weekly gigs. Tourists were already filling the strip clubs and daiquiri shops of Bourbon Street and the trendy restaurants of the recently gentrified Bywater neighborhood. And in Mid-City, in front of the First Grace United Methodist Church, a couple of women stood beside tables selling tacos and mondongo (pork-belly soup) to an intergenerational mix of Latino families.

The families were on their way to the church for the weekly gathering of the Congress of Day Laborers. El Congreso, as it’s called for short, fights for equal treatment for the city’s recent Latino immigrants, and every Wednesday as many as 400 members come together to discuss ways to solve problems as varied as wage theft and deportation. As they settled into the pews, Leticia Casildo kicked off the meeting with a fiery call to action: “¡Fuera la migra de Louisiana!”—or, “Kick the immigration-enforcement agents out of Louisiana!”

There was no chanting at the BreakOUT meeting just over a mile away, in a former produce warehouse that is now a collection of artists’ studios and offices, but there was laughter. BreakOUT is an LGBTQ criminal-justice reform organization, and on this evening, a dozen transgender and gender-nonconforming young people were working and gossiping, creating a safe space behind a door with a welcome mat that read: come back with a warrant. The room felt like a mix of social club and office. A meeting started with a countdown exercise that looked like a free-form dance party, but soon those gathered got down to the business of assigning tasks for an event on the coming weekend. “Sometimes, I’ll just be so blown away to see how strong these youth are and how they constantly just keep fighting,” says Milan Nicole Sherry, 24, one of BreakOUT’s founding members and now a staffer. “They don’t take no for an answer.”

The rebel spirit continued about half an hour later and a few miles uptown, as roughly 100 people sat in a wide circle inside a Unitarian Church. The multiracial group, called Gulf South Rising, had come together to discuss grassroots responses to the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. Its members were frustrated with the official commemorations, which are designed to highlight the city’s resilience and which, critics say, work to obscure and conceal the systemic injustices at play.

That’s a theme that was picked up, like a relay baton, at another meeting back in Mid-City, of a group of mostly young white activists from an antiracist organization called European Dissent. Founded in the 1990s, when Klansman David Duke ran for governor of Louisiana, the group has more active members now than at any point in its history. Many of its members moved here in the past few months and are concerned about their contribution to the displacement that’s defined the city since Katrina. On the evening’s agenda: strategies to fight gentrification.

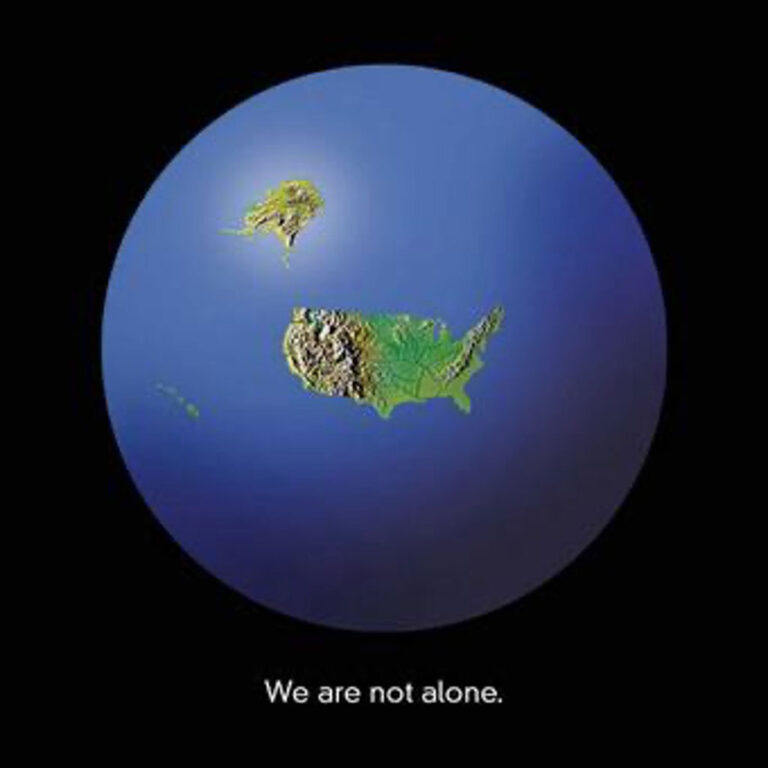

This is New Orleans 10 years after Hurricane Katrina—a town of ferment and possibility, open wounds and agitation. It is whiter, wealthier, and smaller than it was on August 28, 2005. Around 100,000 black residents are still displaced, scattered to places unknown; housing prices continue to rise rapidly, pushing out those trying to get by on jobs in the city’s low-paying tourism economy. But despite the violence represented by these changes, or perhaps because of them, New Orleans has also seen a rise in coordinated resistance. More people have been organizing, taking to the streets, and risking arrest than at any other time in recent history.

Continue reading at TheNation.com

Excerpt from A Movement Lab in New Orleans © 2015 by Jordan Flaherty. Used with permission from The Nation.